Scientists Find Strong Evidence Of Water Plumes Erupting Off Jupiter’s Moon Europa

Thanks to NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, astronomers have spotted water vapor above the icy South Pole region of Jupiter’s moon, Europa, providing the first strong evidence of water plumes erupting off the satellite’s surface, and potentially enabling scientists to understand if Europa could be suitable for human habitation.

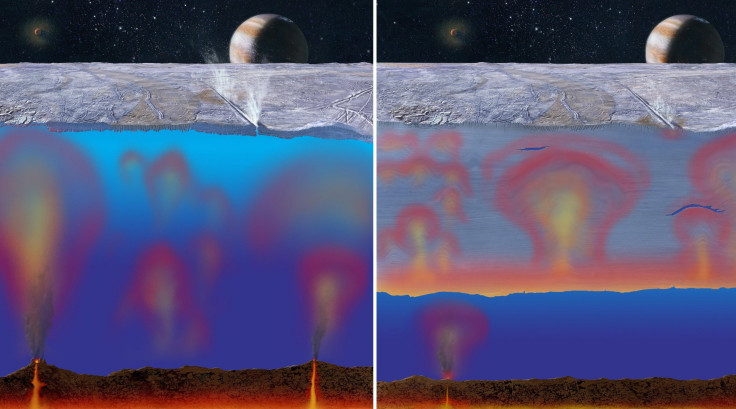

According to previous findings, Europa’s icy crust covers an ocean underneath, and while researchers are not sure whether the water vapor is caused by the water plumes on Europa, they believe it to be the most likely explanation for the discovery. The findings were published in the Thursday issue of Science Express.

“If those plumes are connected with the subsurface water ocean we are confident exists under Europa's crust, then this means that future investigations can directly investigate the chemical makeup of Europa's potentially habitable environment without drilling through layers of ice. And that is tremendously exciting,” Lorenz Roth of Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, Texas, and the study’s lead author said in a statement.

The researchers said that if further observations confirm the findings, Europa would be the second moon in the solar system to have water vapor plumes. In 2005, NASA's Cassini orbiter detected jets of water vapor and dust spewing off the surface of Saturn's moon, Enceladus.

Hubble provided the evidence for Europa's plumes in December 2012, while time sampling of Europa’s aurora emissions helped researchers distinguish between features created by charged particles from Jupiter's magnetic bubble and plumes from Europa’s surface.

“We pushed Hubble to its limits to see this very faint emission,” Joachim Saur of the University of Cologne in Germany, and the study’s co-author, said in the statement. “These could be stealth plumes, because they might be tenuous and difficult to observe in the visible light.”

According to Roth, long cracks on Europa's surface, known as lineae, might be venting water vapor into space. Cassini has seen similar cracks that host Enceladus' jets.

In addition, similar to Enceladus, the Hubble team found that the intensity of the plumes varies with Europa's orbital position. Active jets have been seen only when Europa is farthest from Jupiter and no sign of venting has been detected when Europa is closer to Jupiter.

The researchers attempted to provide an explanation for this variability, saying that the cracks on Europa's surface experience more stress as gravitational forces push and pull on the moon and open vents at larger distances from Jupiter. The vents are narrowed or closed when the moon is closest to the giant, gaseous planet.

According to Hubble's measurements, Europa experiences about 12 times more gravitational pull than Enceladus, which prevents the vapor from escaping into space, as it does on Enceladus. Instead, the vapor falls back onto Europa’s surface after reaching an altitude of 125 miles.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.