Scientists Revive Deep Sea Microbes Dormant For 100 Million Years

KEY POINTS

- The microbes the researchers revived were from sediments deposited 101.5 million years ago

- They were quickly ready to eat and even multiplied within days after incubation

- The study shows how there are 'no limits' to life in the oceans

A team of researchers revived ancient microbes that have been dormant at the bottom of the sea since the time of dinosaurs. Given the right nourishment, the microbes were quickly able to grow and divide.

It was 10 years ago when an international team of researchers collected sediment samples during an expedition to the South Pacific Gyre. Scientists have been collecting such specimens from the seafloor to have a better understanding of past climates as well as the deep sea ecosystem.

For the new study, the researchers were not looking to understand the conditions in the past but, to see whether life could exist in a nutrient-poor environment such as the South Pacific Gyre, which is a part of the ocean with poor nutrient availability. Its center is called the "oceanic pole of inaccessibility" and is regarded as the largest oceanic desert on Earth.

"Our main question was whether life could exist in such a nutrient-limited environment or if this was a lifeless zone," study lead Yuki Morono of Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC) said in a news release from The University of Rhode Island (URI). "And we wanted to know how long the microbes could sustain their life in a near-absence of food."

During the 2010 expedition, the researchers drilled into sediment cores up to 6,000 meters below the seafloor and, found that all the cores had the presence of oxygen. This suggested that oxygen may be present even in the very deep parts of the ocean as long as the sediment accumulated slowly.

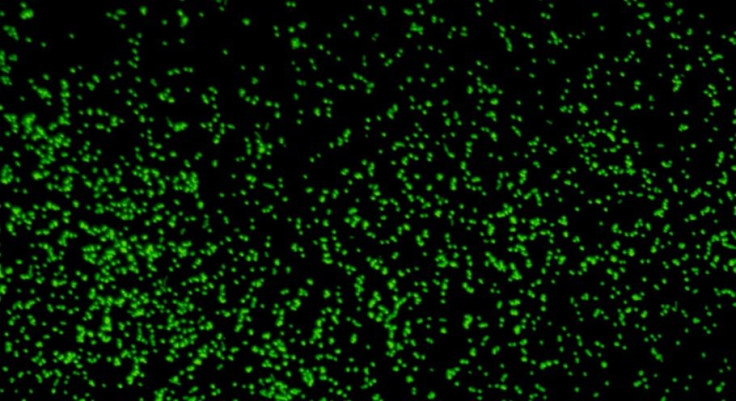

As part of the study, the researchers tried to see whether the microbes they collected were still capable of feeding and dividing by providing them with carbon and nitrogen substrates. These samples were from the oldest sediment that they drilled and have been dormant for 100 million years.

Amazingly, the ancient microbes were actually alive and ready to eat and grow. The microbes quickly responded to the carbon and nitrogen substrates and even increased in number within 68 days after incubation.

"At first I was skeptical, but we found that up to 99.1% of the microbes in sediment deposited 101.5 million years ago were still alive and were ready to eat," Morono said.

How the microbes survived for such a long time remains a mystery that the researchers are hoping to uncover. They are also hoping to understand how or if the microbes evolved in the subseafloor.

"What's most exciting about this study is that it shows that there are no limits to life in the old sediment of the world's ocean," study co-author Steven D'Hondt of URI Graduate School of Oceanography said. "In the oldest sediment we've drilled, with the least amount of food, there are still living organisms, and they can wake up, grow and multiply."

The study is published in the journal Nature Communication.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.