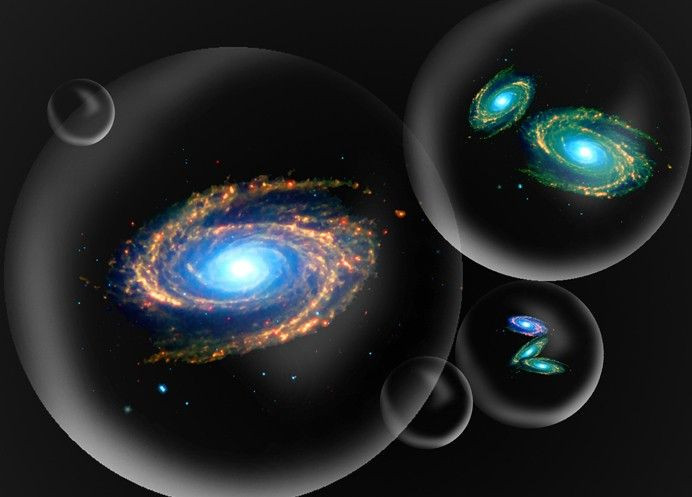

Scientists: We Live in a Bubble Inside a "Multiverse"

Two papers recently published by scientists theorize that our universe might be contained in a bubble, and that there are other universes contained in numerous other bubbles, making up a "multiverse".

Physicists from the United College of London, Imperial College of London and the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics are now conducting tests to look for clues to determine whether or not this is the case.

The two papers that were published in Physical Review Letters and Physical Review D detail for the first time scientists' attempts at searching for traces of a multiverse.

Since physicists and astronomers don't have the technology or means to peer beyond our universe to see other universes, they are hoping to confirm their theory by looking for signs that our universe at one time collided with another universe. The traits that they are searching for are disk-like patterns leftover within the background radiation of our universe.

If traits of a multiverse are discovered, it would greatly increase our view of the space we live in. Currently, our view of the known universe is a diameter of 93 billion light years, or 28 billion parsecs.

Physicists theorize that other universes outside of our own contained in other bubbles may be fundamentally different in their laws of nature and constants.

In order to search for the disk-like patterns, the team developed an algorithm to trove through data collected by NASA's Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP).

The WMAP probe, launched in 2001, was built to "make fundamental measurements of cosmology" according to NASA. The probe is credited for producing today's Standard Model of Cosmology.

Stephen Feeney, a Ph.D student at the United College of London and creator of the powerful algorithm, told Science Daily "The work represents an opportunity to test a theory that is truly mind blowing: that we exist within a vast multiverse, where other universes are constantly popping into existence."

The team also took extra steps in the development of the algorithm to assure that they would not come to a premature conclusion based on random data. Strict rules were imposed on the algorithm to analyze the discovered patterns and to determine whether or not the patterns fit what the physicists are looking for or if they are occurring by chance.

Another one of the co-authors of the published papers, Dr. Daniel Mortlock said "It's all too easy to over-interpret interesting patterns in random data (like the 'face on Mars' that, when viewed more closely, turned out to to be just a normal mountain), so we took great care to assess how likely it was that the possible bubble collision signatures we found could have arisen by chance."

As the study progresses, the team intends to include data from the European Space Agency's Planck satellite as well. But for the time being the first results from the team will not be conclusive until further testing is done.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.