The Secret 'Humiliation' Of Romania's Star Gymnast Comaneci

Behind the glamour and success, beatings and humiliation: a new book about Romania's legendary gymnast Nadia Comaneci delves into the archives of the feared communist-era Securitate secret police that record the abuse she suffered even while being feted for her sporting glories.

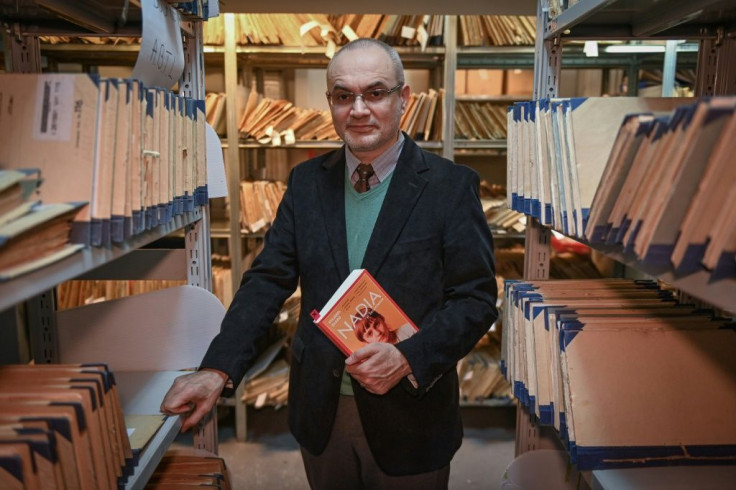

"Nadia si Securitatea" (Nadia and the Securitate), written by historian Stejarel Olaru, was published earlier this month and is the fruit of his trawls through thousands of pages of declassified Securitate reports.

In them, informants and tapped phone calls detail what Olaru calls the "abusive relationship" between Comaneci, now 59, and her coach, Bela Karolyi.

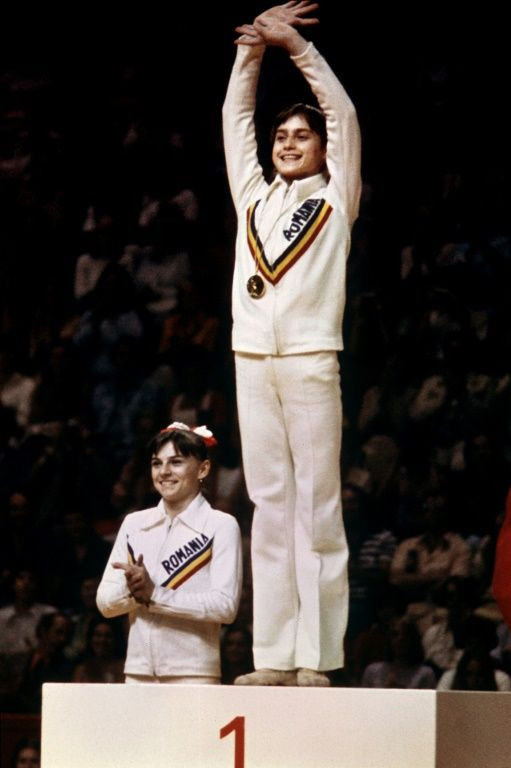

A multiple Olympic, world and European champion, who made history at the 1976 Montreal Olympics with the first-ever "perfect 10" score for her routine on the uneven bars, Comaneci was given the codename "Corina" by the Securitate in the 1970s.

The secret police of one of the Eastern Bloc's most repressive states watched her every move.

This was achieved through a surveillance apparatus including not only secret agents but also a constantly updated network of informants which Olaru says spanned coaches, doctors, gymnastics federation officials and even the team's choreographer and pianist.

The reports they wrote speak of the "attitude of terror and brutality" displayed by Karolyi towards Comaneci and his other charges.

"The girls were hit until their noses bled and punished through physical exercises to the point of exhaustion", wrote an informant in 1974.

According to the reports, Karolyi made a habit of calling the gymnasts "fat cows" and "pigs", while also taking part of the prize money they won at international competitions.

The coach responded to critics, saying, "By nature I am never satisfied: it's never enough, never.

"My gymnasts are the best prepared in the world. And they win. That's all the counts."

Karolyi defected to the United States with his wife Martha in 1981, and while American champions trained by the couple have previously alleged abusive methods, Comaneci herself has always remained relatively discreet on the matter.

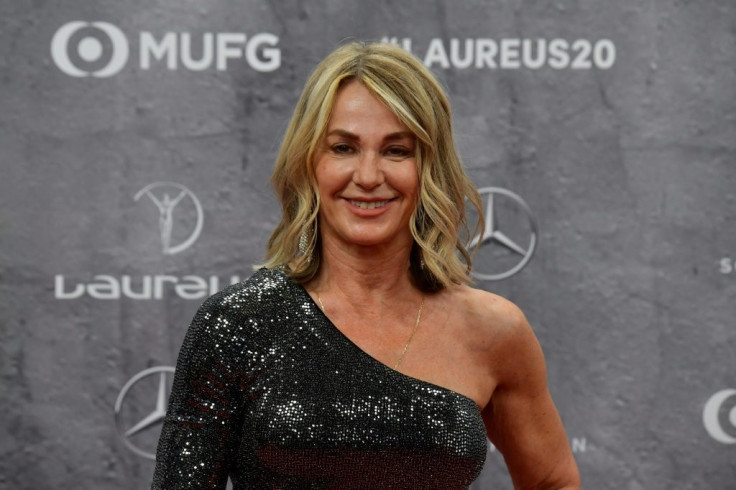

While Comaneci has not given any interviews herself on the latest book, she confirmed to AFP that she had been in touch with Olaru and answered some of his questions.

Karolyi and his wife have denied allegations that they mistreated athletes at the US training facilities they set up after leaving Romania.

They spoke out in an interview with NBC over their links to Larry Nassar, the former USA National Gymnastics team doctor. He worked at their training centre and was later sentenced to life in prison over the sexual abuse of multiple young female gymnasts.

In the book, Comaneci's own words are reported in the form of a 1977 interview with two journalists which was never published but ended up in the Securitate files due to the bugging of her home in the city of Onesti.

In it she confirms having been repeatedly "insulted" and slapped, deprived of food for three days and scolded for putting on 300 grams of weight.

"Too many things have happened (...), I can't even look at him anymore," Comaneci is recorded as saying about Karolyi.

Six months after her feat in Montreal, she refused to continue training with Karolyi.

Comaneci's mother had complained to the gymnastics federation about her daughter's treatment and even asked to speak directly to Ceausescu.

An audience with the dictator was organised but then cancelled at the last moment, without explanation.

Ceausescu had "used (Comaneci) for propaganda purposes" and named her a "Heroine of Socialist Labor", Olaru notes, "but she was nevertheless tormented, intimidated, humiliated", even if she was beaten less often than her colleagues.

Karolyi was himself the object of surveillance by informants, who painted him as "manipulative" and "unmoved by human suffering".

He was a member of the country's Hungarian minority, who were often viewed with suspicion by the communist authorities.

Why then didn't authorities intervene over his behaviour?

Olaru puts it down to "pure political calculation".

"How could they have boasted of the high level of the gymnastics programme and at the same time lead an investigation against Karolyi?" Olaru asks.

After retiring from gymnastics in 1984, Olaru says Nadia became "a prisoner in her own country", banned from travelling abroad -- with the exception of some socialist countries.

Nonetheless, she managed to escape to Hungary in 1989 and from there headed first to Austria and then on to the United States, where she requested asylum.

Olaru writes that her decision "bewildered the regime", which now faced being described in the foreign media as "unbearable even for the privileged".

The last known Securitate report concerning Comaneci is from December 20 1989, two days before the fall of Ceausescu.

"Far from having been privileged, as she was presented at the time, Nadia was a victim of the regime," says Olaru.

He sees her as a "rebel" and a "fighter who was able to recover after ordeals she went through".

"She did what she had to in order to fulfil her ambitions," he says.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.