Secrets Of Hoxha's Henchmen Still Poison Albania

Three decades after the fall of communism, the files held by Albania's infamous secret police on "enemies of the state" are slowly revealing their secrets.

Yet some of the victims of the paranoid dictator Enver Hoxha -- whose dreaded Sigurimi had more than 10,000 informers and even more collaborators -- cannot bear to look.

Since 2017, the small Balkan country has allowed people to consult their files.

But some are afraid of finding that friends or neighbours betrayed them.

"I do not want to see my file," journalist Cerziz Loloci, 62, told AFP.

"I am afraid of learning I was betrayed by a close friend and it would break my heart."

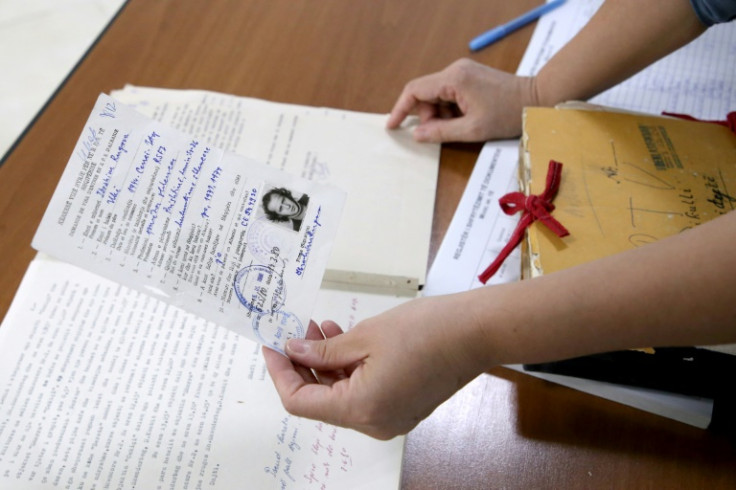

But thousands of Albanians and dozens of foreigners have dared to confront the dark past when Albania was one of the most repressive countries in the world.

The file on Luc Bouniol-Laffont, who was cultural attache at the French Embassy in Tirana from 1988 to 1990, runs to 774 pages.

"It is fascinating and also terrifying to see how they made the young man of 25 that I was then -- simply curious and open to others -- a dangerous spy threatening the security of the regime," he said.

The Sigurimi mobilised dozens of people to "create a completely imaginary scenario, worthy of a spy movie or a tragicomic novel," said Bouniol-Laffont, now a senior executive at the Louvre museum in Paris.

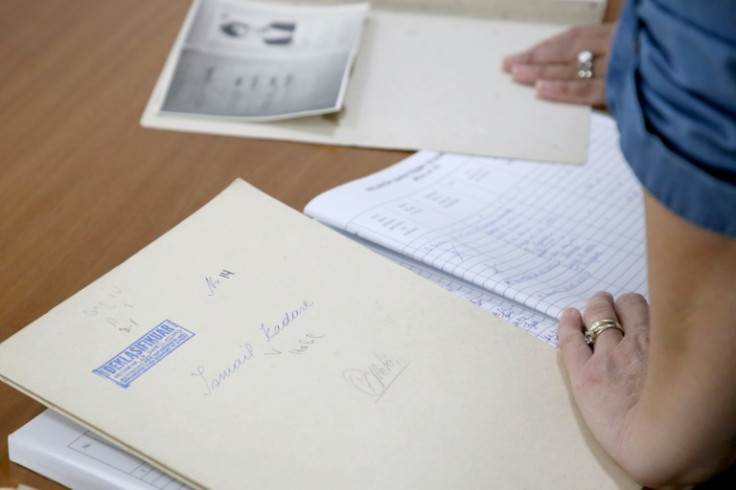

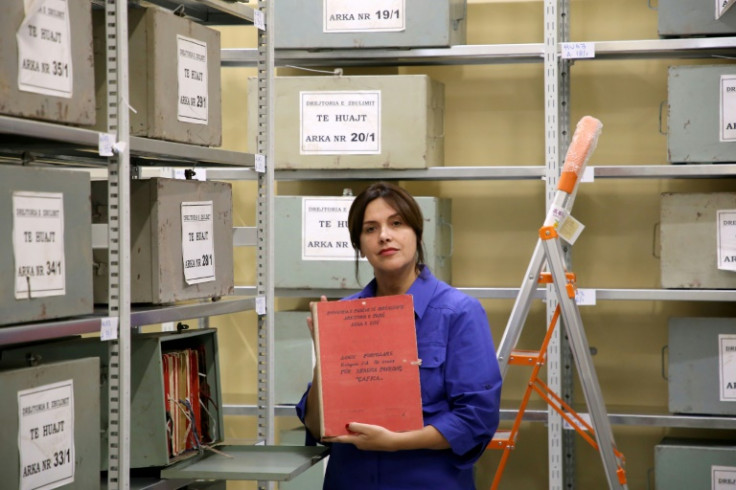

The Sigurimi archive of more than 20 million documents is held in a basement inside a secure compound of the Albanian Ministry of Defence.

Files are stocked in four rooms filled to the brim with documents, photographs and microfilms, carefully stored in iron boxes that resemble coffins waiting to be opened.

Their contents are testimony to the regime's brutality, said the archive's director, Gentiana Sula.

"Comparing the files with those of some other former communist countries, the political violence in Albania was extreme," she said.

In a country of less than three million people, more than 100,000 were interned in camps, 20,000 imprisoned and 6,000 killed or disappeared between 1944 and 1991.

The Sigurimi spied on "internal enemies", foreigners working in Albania and even on visiting tourists. Some of their informers were volunteers, but others were forced to work for them.

During Hoxha's four-decade reign, Albania fell out with the whole world, including fellow communist nations such as the Soviet Union, China and neighbouring Yugoslavia.

All foreigners, including Albanians from Kosovo, then part of Yugoslavia, were seen as a potential threat. Even Ibrahim Rugova -- the leader of the struggle for Kosovo's independence -- had a file.

Countries were classified using nicknames -- the "Shark" referring to the United States, the "Viper" to the former Yugoslavia and the "Branch" to Kosovo.

Canadian journalist Nadi Mobarak found that his late father Melhem -- a Lebanese-born researcher with a passion for Albanian history -- had also been monitored.

"I believe that his coming to Albania has nothing to do with tourism," a police official reported. "Rather, he is seeking to learn more about our country for foreign interests. He could have been mandated by the Americans or the Yugoslavs."

"My father would have had a lot of fun going through the pages of this file," Mobarak said.

But the subject remains highly sensitive in Albania where even unsubstantiated accusations of collaborating with the Sigurimi carries a heavy stigma.

Sula said many informers were forced to collaborate under torture, psychological pressure or threats against their relatives.

The Sigurimi may be long gone, but it still poisons public life, with rumours of links to the hated secret police often used to blacken political rivals.

The authority that looks after the archive is calling for a change in the law to allow it to vet candidates for public office -- even if they have previously passed background checks, as records were incomplete in the past.

Albania's most famous writer, Ismail Kadare, was the first to publicly request access to his Sigurimi surveillance file. He said it is important to face up to history.

"To continue to remain silent about the past is to continue to obey the morality of the dictatorship, to continue to lose one's moral bearings," Kadare told AFP.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.