From The Shadows: The Secret, Threatened Lives Of Bats

It could be a scene from a bad horror movie: Torchlights slice through the darkness inside a church in western France as the building echoes with the shrieks of hundreds of bats.

But these creatures of the night are scaring no one.

They are having their annual check-up, as scientists try to unravel the secrets of an animal whose fiendish reputation has eclipsed its many gifts to the world.

Dozens of Greater Mouse-eared bats are passed from hand to hand -- gloved to avoid a bite -- by volunteers and scientists in Saint Martin's church at Noyal-Muzillac, in Brittany.

Each bat is painstakingly examined, its sex, height and weight noted, its blood taken, teeth checked for wear, translucent wings stretched out and inspected.

A male pup, born just a few weeks ago in the church rafters, is hanging upside down by its claws in a tube placed on a weighing scale: 19.7 grams (0.7 ounces).

Once the physical assessment is finished, the latest addition to the colony is implanted with a tag, no bigger than a grain of rice.

"They put a little microchip like you would a dog or a cat, it's called a pit tag, under the skin on these bats when they are babies and they release them," said Emma Teeling, head of zoology at University College Dublin.

This is a ritual that has been repeated every year for a decade by the organisation Bretagne Vivante, which captures and checks the entire colony to help understand and safeguard this protected dark-furred species.

Why lavish so much attention on such a maligned creature?

Because they are one of the world's most endangered animals -- threatened by habitat loss and by human persecution.

Long demonised as fanged monsters or vectors of disease, the pandemic has done little to improve bats' image, after the World Health Organization said the coronavirus likely originated in the animals.

Rodrigo Medellin, who co-leads the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Bat Group, said he has never worked harder to defend them.

But the only mammal capable of flight has a lot more to offer than viruses and vampire legends.

If you have ever sipped coffee, eaten a taco or worn a cotton t-shirt, you can thank bats, Medellin told AFP.

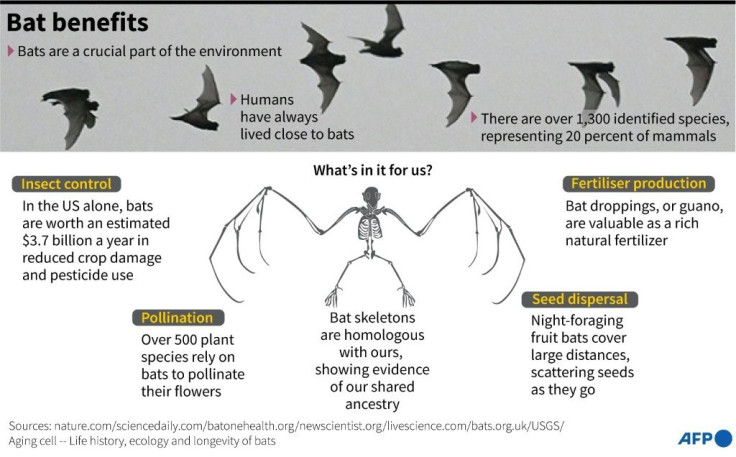

Fruit-eating species help disperse seeds from tree to tree, while some bats are indispensable pollinators.

Some species can swallow half their weight in insects each night, according to Bat Conservation International.

"They are the best natural pesticide," said Medellin, of Mexico's Universidad Nacional Autonoma, adding that even tequila can be traced to millions of years of bat pollination of the agave plant.

"The benefits we receive from them are so huge and so different that they touch every day of our life," said Medellin.

But it is not just what bats do that makes them special.

They also have an array of innate talents that fascinate scientists.

Engineers are inspired by their natural sonar, enabling them to fly low and find their way thanks to echolocation.

And yes, they can harbour viruses like coronaviruses or Ebola. But why do they not fall ill?

Bats also seem to have evolved a way to slow down the ageing process, said Teeling, whose lab in Ireland is exploring how these creatures stay healthy almost until the end of their lives.

Little animals typically "live fast, die young", she said, explaining that a reduced body size often means a fast metabolism: the lifespan of a mouse is often measured in months, while a bowhead whale can live for over a century.

"In nature, when you look at the body size of something, you can predict how long they are going to live for," she said.

Not bats.

The Greater Mouse-eared Bats that Teeling and her colleagues study do not exceed eight centimetres (just over three inches), but they can live up to 10, or even 20 years.

In 2005, researchers in Siberia captured a Brandt's bat that had been tagged 41 years earlier, estimating it had lived nearly 10 times longer than expected for its size.

From the tiny two-gram "bumblebee bat", to the giant Philippine flying fox with its 1.5-metre (five-foot) wingspan, bats make up a fifth of all terrestrial mammals.

But some 40 percent of the 1,321 species assessed on the IUCN's Red List are now classified as endangered.

"We are losing species all over the world," said Julie Marmet, chiropterologist (bat expert) at the National Museum of Natural History in France.

Bats have been "resilient" for 50 million years, she told AFP, but today's changes are "far too fast for species to adapt".

Human actions are to blame, as with the biodiversity crisis gripping the entire planet -- which will come under the spotlight at the IUCN congress in early September.

Deforestation and habitat loss is the primary driver.

Many species live in trees and the 40 percent that live in caves depend largely on forests for foraging, said Winifred Frick, chief scientist at Bat Conservation International.

Climate change is also increasingly taking its toll.

Flying foxes in Australia have been devastated by heatwaves, while in the United States thousands of Mexican free-tailed bats have been killed by hypothermia.

Lured by milder winters into abandoning their habitual migration south, many of these little bats have taken to staying in their roosts under bridges in Texas during the cooler months.

These bridges over waterways look like "restaurants" for bats, said Frick, but it also represents an "ecological trap".

During the last winter, there was a particularly cold snap in Texas.

"Thousands and thousands of bats died during that big freeze," she said.

Modern human infrastructure has become a perilous obstacle course.

Already victims of collisions with cars, they must now avoid wind turbines -- studies suggest half a million are killed every year in the US either by the blades or the deadly effects of the forceful air movement.

Even the automatic motion sensors that illuminate the stairways of apartment blocks can turn a short stopover for migrating pipistrelles into a waking nightmare.

Normally these matchbox-sized bats only fly at night, said Andrzej Kepel, of the Polish association Salamandra.

But when they try to continue with their migration after a couple of days in these stairways, they trigger the sensor and the lights turn on.

"So they land," said Kepel. Again and again they try to leave and every time the lights flick on, stopping them.

Their cries can attract others.

"After several days, there are hundreds of bats in the staircase and people are panicking," he said. Bats can end up starving to death.

Inside caves, they are still not safe.

Whether it is tourists shining torches or the incursions of those collecting bat guano to use as fertilizer, the slightest disturbance can be devastating.

Especially since most bat species only have one baby per year, unusually for such a small mammal, said Marmet.

So "if there is a problem in a colony, it's over."

Hunted for meat or sport by people in Southeast Asia and Africa, they also fall prey to other animals.

In Jamaica, for example, cats have staked out the cave of a colony of critically endangered bats.

"We've documented within an hour cats taking about 20 bats, ripping their wings off and snacking on them," said Frick.

So who is frightening who?

Bats have not always had a bad reputation.

In Mayan culture they played a major role in the forming of the universe.

But in the Western world they have been unwittingly typecast as mascots of Halloween and horror films.

While just three types of bats in South America are (animal) blood-drinking "vampires", when Bram Stoker wrote "Dracula" in the 19th century it tarnished the reputation of the whole family.

"That is the moment bats began to be accused of being envoys of the devil, being evil, and filthy, and bringing diseases," said Medellin.

Batman was helpless to redress the balance.

Even Pope Francis last year likened people in a state of sin to being "like 'human bats' who can move about only at night".

But many of those who spend time with bats end up loving them.

"They are cute! We get attached to them," says Corentin Le Floch, of Bretagne Vivante.

In the church of Noyal-Muzillac, it's snack time and a Greater Mouse-eared bat is nibbling on a wriggling mealworm.

He gets a quick caress of his little pointy ears and then: freedom.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.