As The Sharing Economy Grows, Labor Advocates Propose A New Approach To Worker Rights

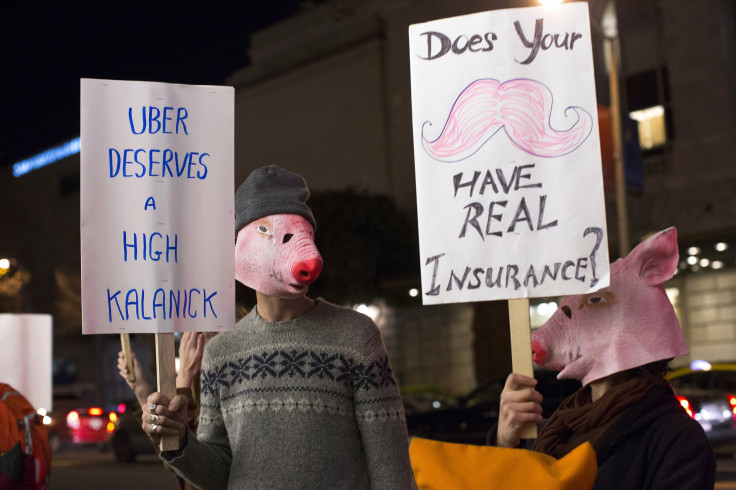

Armed with a steady Internet connection, consumers can summon drivers, cleaners and couriers to their homes in the span of minutes. Behind that jaw-dropping efficiency, however, is a deeply contentious business model. Since they’re usually classified as independent contractors -- not employees -- the people who provide those lighting-speed services are not entitled to minimum wage or overtime pay, let alone workers’ compensation in the case of an accident. On Wednesday, labor advocates demanded an overhaul of that system.

Calling on Uber, Lyft and others to classify their workers as employees instead of independent contractors, a new report from the left-leaning National Employment Law Project (NELP) promises to fuel the debate about how long-standing employment laws apply to the so-called sharing economy. Alleged misclassification is at the heart of a high-profile class action against Uber. It’s also the subject of a recent administrative guidance from the Department of Labor, which declared that “most workers are employees.”

But the NELP report goes a step further than the misclassification question.

It also calls on lawmakers to extend eligibility for basic workplace benefits like Social Security and unemployment insurance to workers in the on-demand economy, regardless of how they’re classified by their bosses.

“Rather than forcing workers to litigate the issue of employee status on a case-by-case basis in a variety of contexts, Congress and state policymakers could provide for direct, automatic coverage of on-demand workers under core labor laws,” Rebecca Smith and Sarah Leberstein, the report’s co-authors, wrote.

Some states already do this for independent contractors -- albeit in a limited way. New York state, for instance, has a broad definition of “employment” for the purposes of workers' compensation: A trucking firm in the New York City borough of Queens might label its drivers as independent contractors and avoid certain payroll taxes, but it’s still required to purchase workers' compensation insurance. Likewise, workers who get injured on the job are, in theory, eligible for benefits.

As labor advocates grapple with the question of how to provide protections for workers in the so-called gig economy, the report suggested a path to success: Passing laws that explicitly extend basic labor rights to these workers may prove easier than filing an endless stream of class actions over misclassification.

Miriam Cherry, a professor at the Saint Louis University School of Law, applauded this approach to workers’ rights. “Otherwise, it’s going to be decided in this weird piecemeal way,” she said. “If nobody does anything about it, then the courts are going to decide.”

Cherry pointed to the long-standing debate over FedEx’s classification of delivery drivers as independent contractors. One court may rule that the drivers are employees; another may disagree. By one judge’s logic, the drivers are eligible to form unions and are protected from employer retaliation under the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA); by another judge’s logic, they have no such rights as independent contractors. Amending the NLRA altogether to cover these sorts of workers could be a simpler route for labor advocates than duking it out in the courts and getting contradictory rulings.

In a similar vein, NELP researchers support recent efforts from local governments to extend collective-bargaining rights to "on-demand workers" at firms like Uber and Lyft. The Washington suburb of Montgomery County, Maryland, recently passed an ordinance setting up a taxi commission represented by the public, drivers and cab companies that's designed to resolve disputes. Seattle, meanwhile, is considering a plan to create its own bargaining system for cab and Uber drivers, even though they’re independent contractors. (Critics contend that the Seattle proposal violates federal law.)

Representatives from Uber, Postmates and Sidecar did not respond to requests for comment. When asked about the proposals, Lyft spokeswoman Chelsea Wilson said the company’s drivers “are not employees.” She said, “They use Lyft and other on-demand services as a flexible and reliable way to make ends meet without having to be stuck in a schedule that doesn’t work for them.”

Setting aside one’s opinion of ride-hailing firms like Uber, Cherry said it’s important to recognize that not every driver sees his or her work as a full-time profession. Many are driving upward of 40 hours a week, but others might be devoting just a couple of hours.

“I like where they’re going,” she said of the report. “The question is, is this going to be sweeping too many people under the rug?”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.