Shortchanged By Low Oil Prices, Alaskans Struggle To See A Future Not Financed By Crude

Alaska may soon bid farewell to popular television shows such as Ice Road Truckers, Deadliest Catch and Alaska State Troopers. Amid a mounting state budgetary crisis brought on by low oil prices, Gov. Bill Walker announced earlier this week that he is ending a program that has granted $47 million in tax credits to Alaska-made films and television shows since 2008.

Thanks to money siphoned from oil companies through taxes, Alaska has long been one of the wealthiest states in the country. But after oil prices dropped precipitously last year, state legislators were faced with a stark new reality. When they began drafting the 2016 budget, there was a $3 billion gap between the money they expected to spend and the money they expected to earn.

Filling that gap is a painful yet familiar exercise for Alaska’s policymakers that repeats whenever the price of oil bottoms out. Back in 1986, a crash sent oil prices back to 1974 levels, and approximately 10 percent of the people who were living in the state left. Advisers have long warned that Alaska’s economy must diversify beyond oil in order to break the cycle, yet experts are stumped as to what could possibly replace it.

“In a sense, it's déjà vu,” said Scott Goldsmith, an economist at the University of Alaska Anchorage.

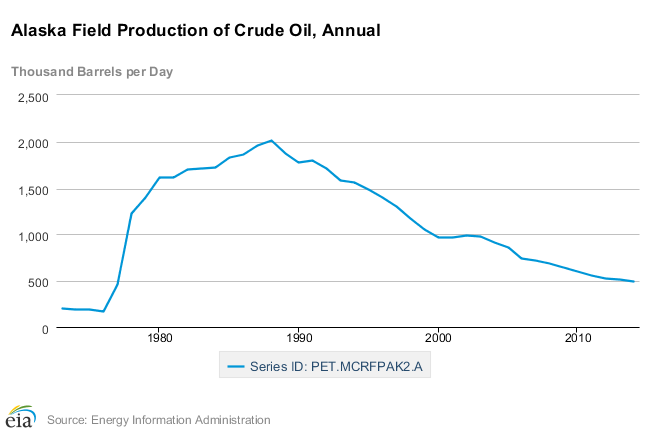

A year ago, Alaska’s Department of Revenue projected that oil could sell for at least $105 a barrel after fetching roughly $110 for the past four years. Instead, the price of Alaskan crude dropped to around $67 a barrel last summer and has remained consistently low. Meanwhile, oil production has also slowed -- the amount of oil transported through the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System has dwindled to only one-fourth its peak rate in 1988.

The pain of fluctuating prices is also felt in other states and countries that rely heavily on revenue from oil to fund basic services. Last fall, Louisiana nixed $171 million from its annual projected revenue to account for a hit to the taxes it will collect from oil extraction. This spring, New Mexico’s Energy, Minerals and Natural Resources Department anticipated a loss of 2,000 jobs in the state’s oil and gas extraction industry due to low prices. Companies in Texas have laid off at least one thousand workers. The government of Venezuela, where oil accounts for 96 percent of the nation’s exports, has struggled to keep food and medicine in stock.

Knapp says these scenarios are predictable, if not easily preventable. “If you have a valuable resource like oil, it's sort of like when people win the lottery,” he says. “You’re kind of dependent and face reductions when the money runs out. And the money almost always runs out.”

The inability of legislators to agree on how to address the gaping hole prompted the governor to mail notices warning of potential layoffs to 23,000 public employees and one representative to send an email to constituents with the subject line: “Ugh.” After an extended legislative session that ran for six months, Alaska’s lawmakers passed a revised budget last week that filled the $3 billion hole with money from a $10 billion fund that had been set aside for a rainy day, thereby avoiding a government shutdown that would have otherwise commenced on July 1.

The newly proposed budget, which Gov. Bill Walker must still sign, includes a provision that allows the state to renegotiate contracts for the salaries of public employees if the price of oil should drop below $45 per barrel or rise above $95 per barrel.

But the problems which stem from the state’s heavy reliance on oil may have only just begun. Both Knapp and Goldsmith say the state will likely run at a deficit for years to come, even if oil prices recover slightly.

Officials are also looking for new ways to raise money -- for example, Alaskans currently pay no income tax or sales tax. But although Knapp says that the state could -- at most -- raise up to $700 million from income tax and $400 million from sales tax, that would still not be enough to replace the amount of money that oil brings in.

Last week, Walker called together 200 politicians, policy advisers, business leaders and economists to spend three days at the University of Alaska Fairbanks to review options for filling the budget gap and reshaping Alaska’s fiscal future. Today, the second-largest sector in Alaska is the federal government – in 2013, the state received $2.8 billion from the federal government which accounted for nearly a fourth of its revenue. Over the years, Alaskans have heard nearly every possible pitch from policymakers for developing an industry or identifying an export that could begin to even slightly wean the state from its reliance on oil and federal money.

In the 1990s, the government spent $120 million on a 15-year plan to raise and export barley, but the project ran up debt and eventually fell apart. Around the same time, a governor proposed building a pipeline that would enable Alaska to sell fresh water from its glaciers and rivers to a parched California. Efforts to expand the state’s mining industry have faced heavy opposition from environmental groups. Another proposal to build fish farms was nixed because it was thought to compete too closely with commercial fishing. Some farmers are betting that peonies can become a major cash crop for the state.

But Knapp points out that even industries such as commercial fishing and tourism which have shown promising growth are not taxed as heavily as oil so don’t generate as much revenue for the state. There are significant barriers to developing new industries such as high transportation costs and a lack of skilled workers. And Knapp says if the state had to offer large incentives to entice new businesses to take root, those payouts could actually worsen the pinch.

“People say – ‘Well, we should diversify the economy’ and it's like, ‘Well, what do you have in mind?’” he says. Goldsmith agrees that while there has been no shortage of creativity in dreaming up industries which could replace the outsized role of oil in the state’s economy – there is a chronic lack of viable options. “If there were some obvious things, they would have happened,” he says.

The state is poised to make its next big bet on a resource that supporters believe has the potential to be another one-hit-wonder just like oil – lawmakers are considering investing $45 billion to $65 billion into a project that would refine, sell and ship natural gas to Asia. While Knapp and Goldsmith both question whether that investment will happen or would ultimately pay off for the state, Goldsmith says at least the scale of the project is on par with the magnitude of the problem it's intended to solve. "We need to think big," he says.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.