Singled Out, Stopped & Frisked In A Distant Land

TOKYO -- I had to travel to Japan to get a taste of what it's like to be singled out, stopped and frisked because of the color of my skin -- something that happens to disadvantaged minorities every day back in New York City.

I had to visit Roppongi, the notorious, gaudy nightlife district of Tokyo still on the State Department's list of destinations Americans are better off avoiding.

It wasn't the Yakuza mafiosi or Nigerian “touts” promising happy endings from big-breasted women inside shady clubs.

It wasn't a drug-spiked drink scam or slick pickpocket that struck me and my friend as we walked in broad daylight, large Canon cameras around our necks.

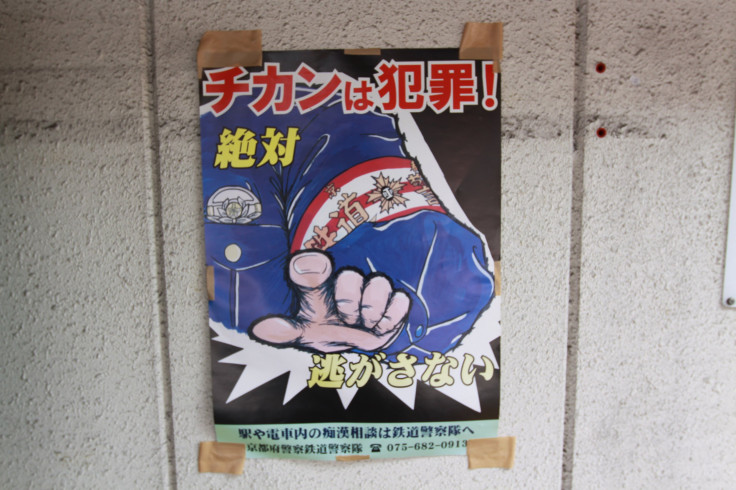

It was the police, in their starched, light-blue uniforms, who left a stain on on my impression of this majestic archipelago.

Not three minutes after we emerged from the subway, two cops approached us, polite as anyone else in this land of deference. “Sorry, Roppongi danger zone,” said one, holding up his white-gloved hands. Speaking no Japanese, we nodded, turned around and began to walk back to the train. Perhaps a serious crime had just occurred up the road.

That wasn't it. We had been selected to be searched.

“Sorry, we must look at your items. Sorry,” the other officer said, bowing repeatedly, hands at his side, as his partner did the same.

Only they didn't just check our pockets. They made us empty them, then took every bill and card out of our wallets and intensely scrutinized them as if they were all possible contraband.

They then patted us down from head to toe -- groped us, really, even running their hands gruffly over our groins.

Then they sent us away, apologizing profusely for the inconvenience. I couldn't manage a response, shocked at what had just happened.

We had been deemed suspicious, and we had been stopped and frisked.

In New York, the police may give us a pass on account of our whiteness, but here we were outsiders, potential criminals to be treated as such.

It wasn't exactly scary at the time, and it was about as intimidating as the TSA check at JFK before my flight to Narita Airport two days earlier. But it was chilling, and unnerving, and disappointing, and racist -- and wrong.

It was everything that New York City Mayor Mike Bloomberg and Police Commissioner Ray Kelly pretend “Stop and Frisk” isn't.

It served as a reminder from the authorities: Your privacy and rights (if the Japanese are even protected from unreasonable searches) are bendable; they're merely obstacles in the path toward a false sense of security. That security breeds a different terror: a fear of the people with the guns, those who can take your freedom, those with power.

Being poor and black or Hispanic in the South Bronx, in Brownsville, in Brooklyn, is an existence fraught with far more challenges than those experienced by two vacationers roaming the streets of Japan.

But in that moment, thousands of miles from home, I felt a deep malaise about the state of justice in America, and the dignity of the hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers who have been violated on the streets of the neighborhoods they call home by those who are charged with serving and protecting them.

I had to go to the Land of the Rising Sun to truly understand what it is to feel singled out because of my race.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.