Sling TV Subscriber Mystery Stirs Frustration As Dish Network Corp Faces More Cord-Cutting

For the first time ever, Dish Network Corp. has shared limited subscriber data related to its over-the-top service Sling TV, but not everyone thinks the company is being as forthcoming as it should.

In a regulatory filing Wednesday, the satellite provider said Sling TV signed up 169,000 subscribers by the end of March, about two months after its launch. But it declined to say how many subscribers it gained since then, opting instead to lump the number together with its traditional satellite subscribers.

The lack of specific data has left analysts in the dark in terms of whether Sling TV has been able to build momentum. And that’s a problem, some say, because Sling is coming to be seen an indicator for where the television industry is heading. With cord-cutting rampant, cable and satellite operators are losing traditional subscribers across the board, and all eyes are turning to over-the-top alternatives.

Sling, in particular, is a closely watched product because it is the only Web-TV service that lets non-cable subscribers live-stream ESPN, the profitable sports juggernaut owned by the Walt Disney Company. As popular as ESPN is, its traditional subscriber base is also shrinking, and on Tuesday, Disney lowered the growth forecast for its cable segment after a disappointing earnings report in which the segment’s operating income dipped 1.2 percent.

If Sling TV and other over-the-top services were performing stupendously, at least there would be a light at the end of the tunnel. But no one really knows how they’re doing.

“Not only does the lack of clear numbers make it hard to evaluate results at Dish Network, it also makes it impossible to evaluate trends for the whole sector, something that has never been more important given the harsh spotlight on cord-cutting in the wake of Disney’s change to guidance,” analyst Craig Moffett, of MoffettNathanson, said Wednesday in a research note.

Moffett said one possible takeaway is that subscriptions for Sling TV “sharply decelerated” after the first few months, which would explain the lack of disclosure.

Dish Network, which reported earnings Wednesday, said it lost 81,000 pay-TV subscribers in the second quarter, almost twice as many as it lost for the same period last year. It said it had 13.93 million total TV subscribers as of June 30, including Sling. Moffett estimated that Sling TV could have averaged 275,000 subscribers during the second quarter, but it’s still just an educated guess.

Aggressive Marketing

Whether Sling is sinking or swimming, it’s not for lack exposure. The service, which offers a slimmed-down bundle of cable channels for only $20 a month, has been among the most-trumpeted over-the-top products out there, in part because the low price point presumably makes it appealing to younger consumers who have no desire to sign up for an expensive pay-TV package.

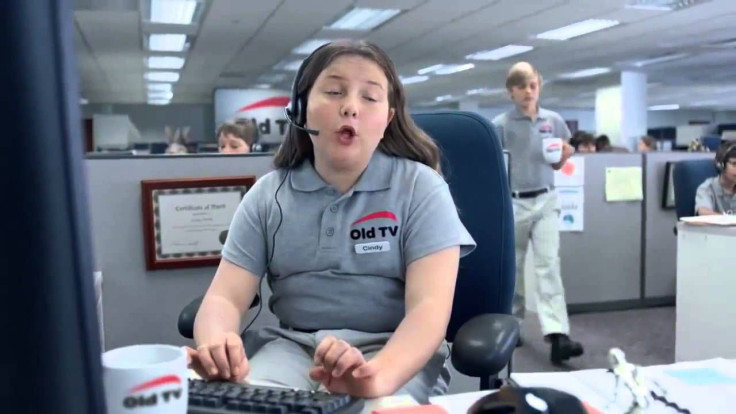

Last month, Sling launched its first ad campaign, a series of one-minute TV spots proving just how aggressively it is going after its target demographic, even if that means luring them away from its own parent company. The commercials feature tough-talking kids intimidating customers into long-term contracts bloated bundles, hidden fees and poor customer service.

In one scene, an angry kid pins down a customer on his front lawn and yells, “You’ll pay for 400 channels and like it,” while wailing him in the face.

The spots are edgy, the direction peppy, and the message is clear: Pay-TV companies are like schoolyard bullies, and consumers are better off without them. It’s a message that is far more antagonistic than it was. When Sling TV first launched earlier this year, the company was careful to say the intended market is “cord-cutters” and “cord-nevers,” thereby positioning the product as going after people who have already made the decision to go without a traditional cable or satellite subscription.

But the new commercials seem to be taking that a step further by actively encouraging people to ditch the old pay-TV model, despite the fact that Sling TV’s owner, Dish Network, epitomizes that old model. So do the folks at Sling TV just like biting the hand that feeds them, or is there something about the pay-TV industry that lends itself to self-loathing?

Glenn Eisen, Sling TV’s chief marketing officer, disagreed that the new commercials signify a deviation from the product’s marketing strategy. “There really hasn’t been a shift,” he told International Business Times. “We’ve always known that our strategic target is millennials. Cord-nevers or cord-cutters represent a segment of the population who have, of their own accord, rejected the pay-TV model.”

Eisen declined to say how many subscribers Sling TV has, but he said he’s happy with the number. He added that the typical Sling customer could be described as a “cord-hater.”

Hate The Company, Not The Service

Steve Beck, a business strategist and managing partner of the consulting firm cg42, doesn’t think it will be so simple for companies like Dish or Comcast -- which recently announced the beta launch of its own streaming service -- to convince disgruntled pay-TV customers to flock to their new products.

“What these companies are failing to recognize is that people are leaving them because of how they’ve been treated,” he said. “They’re leaving them because the business model is broken. They’re leaving them because they don’t like them, and they’re frustrated.”

Last year, cg42 released a brand vulnerability study showing that more than half of all customers with the nation’s top five cable operators would leave their current provider if they had a choice. That could spell trouble for providers looking to woo younger consumers with over-the-top products.

“The cable industry as a whole is unbelievably vulnerable, Beck said. “The levels of frustration that their customers have with them is higher than any industry we’ve ever studied, including the retail banking space in 2010, which was during the era of Occupy Wall Street.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.