Slovenia Bailout: Borrowing Costs Rise Again, High NPL Ratio In Banking Sector Fuel Concern

It’s never fun being the little guy.

Following March’s botched Cypriot bailout, Slovenia emerged as the most likely candidate for the euro zone’s next rescue because of the fragility of its banks. James Howat, an economist with Capital Economics in London, believes “there are good reasons to be worried about Slovenia.”

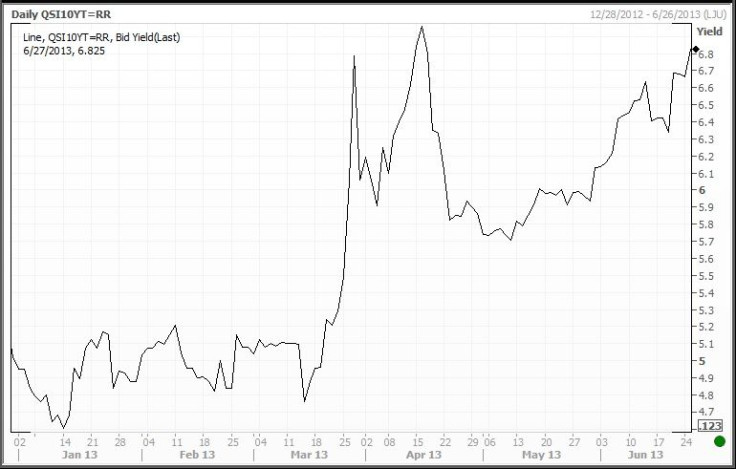

After a relatively quiet period, market pressure on the tiny former Yugoslav republic of 2.1 million people wedged between the Alps and the Adriatic Sea has re-escalated in recent weeks. Yields on 10-year government bonds have drifted back toward 7 percent, a level widely regarded as unsustainably high. All this suggests that Slovenia's new government led by Prime Minister Alenka Bratusek, which announced an ambitious package of reforms earlier this year, has so far failed to reassure investors.

The latest turn of the screw came from credit agency Fitch, which cut Slovenia’s sovereign rating to BBB+ from A-, with negative outlook. In a report last month, Fitch cited a list of factors behind the decision, notably the macroeconomic and fiscal outlook, which has “deteriorated significantly” since its last rating review, in August last year.

The agency now forecasts a 2 percent contraction in real GDP this year – more or less in line with most observers – along with a further decline of 0.3 percent in 2014, when “Slovenia is expected to be one of only two euro zone economies to contract,” Fitch noted. Fitch’s move followed Moody’s downgrade in April, which cut Slovenia to junk status, citing its weak banking system.

It’s not hard to see why markets turned their attention to Slovenia after the Cyprus bailout. Another small country mired in a banking crisis, Slovenia’s economy is still in a tailspin more than four years after its debt-fueled boom came to end. The post-2009 fall in gross domestic product is second only to that of Greece in the euro zone.

In the runup to the 2008-9 crisis, Slovenia had been one of the region’s top economic performers. Real GDP growth averaged 4.6 percent in the decade prior to the crisis, compared to only 2.1 percent in the euro zone, and Slovenia appeared to enjoy one of the strongest fiscal positions in the region, Howat said.

This performance, however, was built on a steep rise in private debt levels. Bank lending exploded from the equivalent of 40 percent of GDP in 2003 to 90 percent in 2008, funding a construction sector bubble and a wave of leveraged corporate buyouts. “Bank lending grew at a similar rate to that in other peripheral economies later forced into bank bailouts,” Howat noted.

As a result of all this, the global financial crisis and the euro zone crisis hit the Slovenian banking sector hard. Although Slovenia’s banking sector is much smaller than Cyprus’, banks’ nonperforming loans, or loans that are either in default or close to it, have risen to 15 percent of total assets from 5 percent in 2009, with the ratio in the three largest banks topping 20 percent. This already makes Slovenia’s nonperforming loan the second-highest proportion in the euro zone after Greece.

The actual amount of bad debt is probably much higher. In a recent report, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development warned Slovenian banks may be “ever-greening” their distressed loans. In other words, Slovenian banks are rolling the bad debts over to avoid recognizing losses. Like many other euro zone members, Slovenia is in recession, with slowing exports and high unemployment. Nonperforming loans may increase further, given that the economy is set to contract by at least 2 percent this year, following a fall of 2.3 percent in 2012.

Yet, Slovenia isn't Cyprus. For one thing, the scale of the Slovenian banking system isn't comparable with that of Cyprus: Bank assets amount to about 150 percent of GDP, compared with about 700 percent in Cyprus. The euro area average is roughly 350 percent. For another, Slovenia isn’t as dependent on financial services for growth as Cyprus was. In Cyprus’ case, financial services and related business services accounted for between one-third and half of the country’s GDP last year. The same industries accounted for about 10.5 percent of GDP in Slovenia.

While it does seem possible for Slovenia to avoid a bailout, Howat said, the road ahead is long and precarious.

The country bought itself some time from creditors in May when it issued two bonds worth a combined $3.5 billion, with a 10-year bond carrying a yield of 6 percent. It will have to tap markets again in the first quarter of 2014 before a 5-year, 1.5 billion euro bond expires on April 2.

Slovenia plans to overhaul its banking sector by transferring most of the nonperforming loans to a newly established "bad bank" over the next couple of months. It’s aiming to cut the budget deficit to 3 percent of GDP in 2015 from the 7.9 percent expected this year. The government plans to raise value added tax by 2 percentage points to 22 percent from July and reduce public sector wages by up to 5 percent.

Howat noted that Slovenia’s fate isn't entirely in its own hands.

The Slovenian government has become increasingly reliant on foreign investors to fund its ballooning debt. “The recent turmoil in global bond markets, which has also pushed up Slovenian yields, highlights the dangers of relying on flighty foreign investors,” Howat said.

While Slovenian government bond yields are below the levels that forced several periphery economies into full bailouts, they're hovering around the level at which Spain requested a bailout for its banks.

“Slovenia is still at risk of the markets forcing the country into some form of program,” Howat said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.