Slovenia Bailout: Will Slovenia Be The Next Cyprus?

Last month, Cyprus became the fifth euro zone member to receive financial help from Brussels to survive a regional debt crisis. Since the Cyprus bailout there has been widespread concern that Slovenia, the tiny former Yugoslav republic of 2.1 million people wedged between the Alps and the Adriatic Sea, could be the next domino to fall in the European debt crisis.

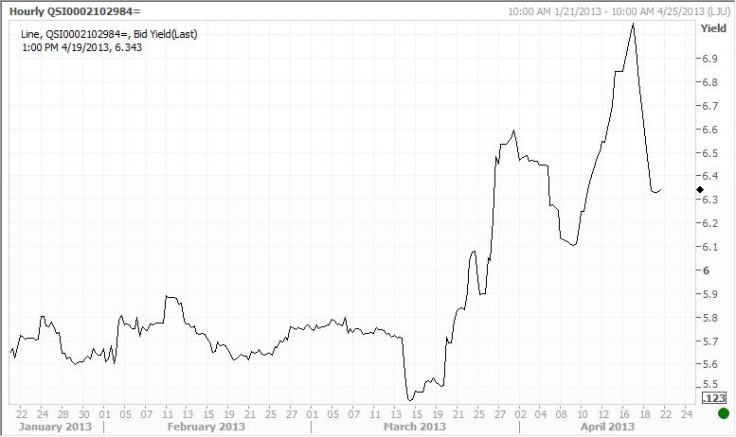

Investors, growing increasingly concerned about the health of this small euro-area country’s banks and the potential cost to the government of cleaning them up, pushed the yield on Slovenia's 10-year benchmark bonds maturing in 2022 up to 7.05 percent -- well above sustainable levels -- on Wednesday before letting it fall back to 6.34 percent on Friday.

UBS economist Gyorgy Kovacs pointed out that Slovenia needs to bolster the confidence of market investors to raise enough cash at reasonable rates to keep its banks and economy afloat.

“It is absolutely essential to restore and maintain market confidence if Slovenia wants to avoid a bailout,” Kovacs wrote in a note to clients.

Like many other euro zone members, Slovenia is in recession, with slowing exports and high unemployment. The country has recorded six consecutive quarters of negative growth since the summer of 2011. Slovenia joined the European Union in May 2004 and became part of the euro area in 2007.

The recession worsened in 2012, with gross domestic product falling 2.3 percent from a year ago and 8.3 percent from its 2008 pre-crisis peak, on the back of strong fiscal consolidation and an abrupt reduction of foreign inflows and credit to the corporate sector. Barclays analysts expect Slovenia’s economy to contract by another 1.9 percent this year.

The International Monetary Fund said in March that Slovenia’s three largest banks could need around €1 billion ($1.3 billion) of fresh capital -- about 10 percent of the country’s entire GDP -- to cover the rollover of its maturing debt, the 2013 budget deficit and the bank restructuring costs, and possibly somewhere between €3 billion and €4 billion in 2014.

The banking sector has been the weak spot in the Slovenian economy. Despite substantial deleveraging in recent years, the loan-to-deposit ratio is still high (at about 130 percent of GDP) compared with the regional average, albeit down from a peak of 160 percent in 2008, according to Barclays analysts Eldar Vakhitov, Apolline Menut and Andreas Kolbe.

Public ownership in the banking system is very high (accounting for about 40 percent of banking loans), with the government having substantial stakes in the three biggest banks: the Nova Ljubljanska, Nova Kreditna Banka Maribor and Abanka Vipa.

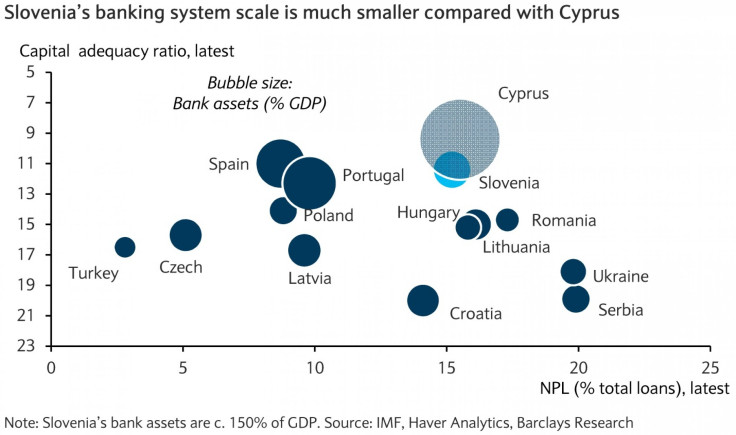

Today, 15 percent of loans held by Slovenia's banks are nonperforming. The six biggest state-controlled banks account for 58 percent of all outstanding loans, and of these 30 percent are nonperforming.

Slovenia Isn’t Cyprus

While both countries are facing significant challenges, analysts noted that there are crucial differences between the Cypriot and Slovenian cases.

“We believe that both the extent and the root causes of Slovenia’s problems are very different from those of Cyprus,” UBS’ Kovacs said.

For one thing, the scale of the Slovenian banking system is not comparable with that of Cyprus: Bank assets amount to about 150 percent of GDP, compared with about 700 percent in Cyprus. The euro-area average is roughly 350 percent.

For another, Slovenia isn’t as dependent on financial services for growth as Cyprus was. In Cyprus’ case, financial services and related business services accounted for between one-third and half of the country’s GDP last year. The same industries accounted for about 10.5 percent of GDP in Slovenia.

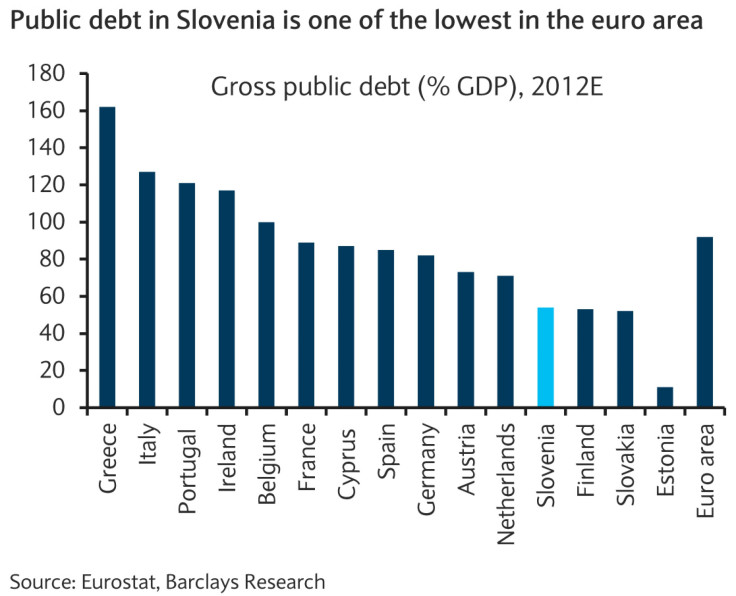

In terms of debt sustainability, although Slovenia’s public debt reached 54 percent of GDP in 2012 -- more than doubling since 2008 – it still remained among the lowest in the euro area.

Barclays’ Vakhitov wrote: “Despite a challenging banking sector and large financing needs, we think the government could avoid the bailout given its relatively low public debt ratio.”

Slovene Finance Minister Uros Cufer said in late March that his country did not need help.

“We will need no bailout this year,” he said, according to Reuters. “I am calm.”

Cufer’s comment followed an assurance by Alenka Bratusek, the new prime minister, that Slovenia would not need international aid and was “capable of sorting things out itself.”

On Wednesday, Bratusek told lawmakers that the government will present a plan to fix the banks within a month. She also pledged to sell two state-owned companies, including a lender. Slovenia does not require a bailout as the country is implementing structural reforms, President Borut Pahor told French daily Le Figaro in an interview. Pahor also said one of the big state-owned banks will be sold off.

Slovenia bought itself some breathing room Wednesday by raising more than $1.3 billion with a bond sale, easing fears that near-term funding problems could force it into an international bailout.

The country issued €1.1 billion of 18-month treasury bills, more than doubles the target, and then repurchased €511 million of similar bills that mature in June.

Although the government has taken some steps to start addressing the challenges Slovenia is facing, there is still considerable uncertainty about many details.

Analysts say the worst scenario would be one in which the reform process is stalled in Slovenia due to political impasses, which could make market access difficult, trigger rating downgrades and raise question marks over Slovenia’s ability to perform under a financial assistance program.

“The key trigger for an ESM [European Monetary System] bailout would be the drying-up of market access at reasonable rates,” Kovacs said. “This could be due to domestic reasons — e.g. the government’s inability to progress with its desired fiscal and banking measures — or general risk aversion.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.