Small Cable Companies To FCC: Set-Top-Box Rules Would Put Us Out Of The TV Business

The FCC is just as annoyed as you are at those set-top-box rental fees you see every month on your cable bill. It’s so annoyed, in fact, that it has proposed rules to “unlock the box” and make pay TV providers allow their programming to be accessed through any set-top box, regardless of the manufacturer — a proposal even President Barack Obama has voiced his support for. The agency wants tech companies like Google to be able to sell you a box that runs on its own operating system.

The Federal Communications Commission and the companies supporting the proposed regulations say their purpose is to break the stranglehold pay TV giants like Comcast have over how consumers take in their content.

But not every cable company has the market power and nearly unlimited resources as Comcast, and for many smaller providers, the FCC’s proposal could be a sucker punch. The American Cable Association, a group of 750 or so of these smaller providers, says such companies are already operating on razor-thin margins when it comes to video customers. Because they have smaller numbers of subscribers — more than half have fewer than 1,000 homes — they have less leverage when it comes to negotiating with networks over the fees they have to pay for programming. In fact, some of them are throwing their hands up altogether when it comes to providing TV services.

And so the ACA said it plans to file a comment to the FCC on Friday excoriating the agency’s proposal to force the industry to accept new, essentially open-source set-top boxes.

These smaller companies, the ACA argues, don’t actually make significant money from set-top-box rental fees. And because many of them are hybrid systems that haven’t been fully digitized, they might not be able to comply with the FCC’s proposed regulations from a technical standpoint or they’ll have to spend so much money rapidly changing their systems that they’ll simply give up on providing TV — leading to even more of a monopoly in the pay TV business.

The FCC’s proposal also ignores what ACA members are already offering their customers, Thomas Cohen, outside counsel for the ACA and a partner at law firm Kelley Drye in Washington, said on a call to reporters Wednesday. Many of these companies are innovating on their own, creating apps through which their customers can access TV on any device they want and teaming up with companies like TiVo to provide set-top boxes.

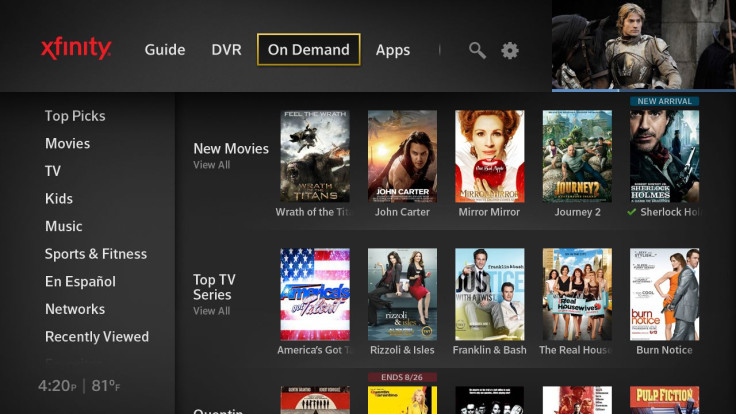

Similarly, even cable giants are getting with the times. Comcast announced Thursday that it’s partnering with Roku and Samsung to make its programming available via Roku players and Samsung Smart TVs through its Xfinity app, eliminating the need for a traditional set-top box.

The FCC was unimpressed, according to this statement it released:

While we do not know all of the details of this announcement, it appears to offer only a proprietary, Comcast-controlled user interface and seems to allow only Comcast content on different devices, rather than allowing those devices to integrate or search across Comcast content as well as other content consumers subscribe to.

In other words, the bee in the FCC’s bonnet is that this solution still involves some friction for the consumer. If you search for something in Comcast’s Xfinity app, it might not return results for shows or movies not in Comcast's system.

But according to a new study from media research firm Leichtman Research Group that polled 1,200 American adults, universal search isn’t really a problem. About 65 percent of those surveyed had a device connected to their TV that allowed them to access content from streaming services like Netflix and HBO, and 70 percent of those with connected TVs found that content easy to get to.

“There are actually more connected TV devices in U.S. households than there are pay TV set-top boxes,” said Bruce Leichtman, LRG’s president and principal analyst. “New forms of competition from Internet-delivered video via connected TVs, along with technological innovations in the pay TV industry, are allowing consumers to choose more options for accessing and watching TV than they have ever had before."

So it feels odd that the FCC wouldn’t at least be somewhat supportive of a solution that took care of its main beef with cable companies: saving consumers $231 per year in set-top-box rental fees.

What is also unclear is how much these third-party boxes would end up costing consumers. The only example we have to go off of is TiVo, which doesn’t necessarily save you money. Yes, you buy your box outright, but you also pay TiVo a monthly service fee. There’s nothing in the FCC’s proposed regulations that would prevent, say, Google (rumored to have a set-top box in development, and a big supporter of the FCC’s proposal) from charging the same kind of monthly fee, and from releasing better boxes every year to which customers would have to upgrade.

Google or some other third-party box manufacturer would also be able to, theoretically, sell its own advertising surrounding the programming streams it would get from pay TV providers, and create its own channel guides that more prominently featured certain networks. Channel position is a huge bargaining chip for providers; taking that away from all of them could have serious financial consequences.

Google, incidentally, will soon begin providing TV listings in search results for movies and TV shows. It has also discovered that becoming a fully fledged pay TV provider, through Google Fiber TV, isn't as easy as it looks.

Pay TV companies are usually the bad guy in any narrative you can come up with. But in this case, they’re the ones shelling out billions of dollars a year in programming fees — Time Warner Cable CEO Rob Marcus revealed in January that his company pays $42 per subscriber per month to TV networks. The companies supporting the FCC regulation aren’t paying a dime.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.