Snowstorm Upstate New York: How Lake-Effect Snow Phenomenon Causes Epic Winter Blizzards [VIDEO]

When winter storm conditions near Lake Erie are just right, the result is almost apocalyptic. This week, an epic – and possibly record-breaking – blizzard pummeled parts of western New York, closing nearly 140 miles of Interstate 90, stranding dozens of motorists and burying homes and roadways in almost six feet of snow. All of that can be blamed on a localized phenomenon called lake-effect snow, an annual weather event that brings heavy snowfall to the Great Lakes’ shores.

The storm that hit upstate New York, including the lakeside city of Buffalo, is being called historic and may top nearly 100 years of winter snowstorms, although official totals have not yet been confirmed. The blizzard left seven people dead and was “basically a knife that went right through the heart of Erie County," County Executive Mark Poloncarz said, according to CNN. "I can't remember and I don't think anyone else can remember this much snow falling in this short a period."

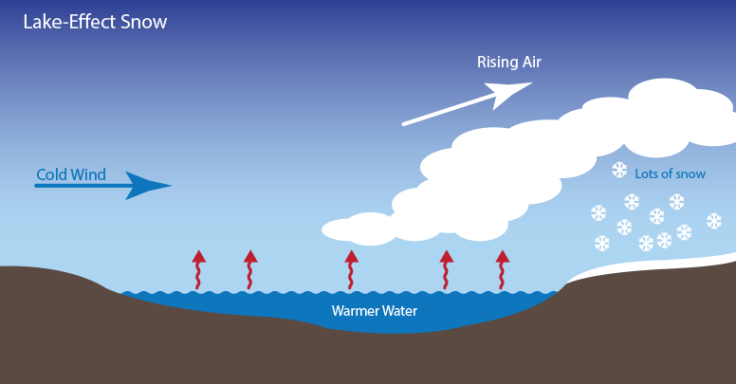

Lake-effect snow is the result of three basic ingredients: frigid air, warm water and a southern wind. It begins when a cold mass of Arctic air swoops in from the north and passes over the Great Lakes. Water holds heat better than air, meaning the lakes are typically much warmer than the air above them, sometimes by as much as 30 degrees Fahrenheit (16.5 degrees Celsius.) This causes low-lying clouds to form as some of the lake water evaporates into the atmosphere and condenses, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The mix of wind and temperature creates a “big sponge” that soaks up water from the lakes and releases it over land in the form of snow.

The snow falls in bands that can be 20 to 30 miles wide and travel over 100 miles inland from the lake. Snow can fall at rates exceeding 5 inches an hour, the NOAA reports. This week's storm was particularly severe because the air was colder than normal and winds blew in just the right direction across a 240-mile stretch of lake, according to the Associated Press.

Lake-effect snowstorms are unique to the Great Lakes region and are most common between November and February. The storms are part of life for residents along the lakes’ shores, where predicting such storms can be a matter of life and death. "Forecasting has come a long way in the past few years, but we still have a lot to learn about the complex interaction of the atmosphere,” Tom Niziol, meteorologist-in-charge at the National Weather Service office in Buffalo, told the NOAA. “As residents enjoy the region’s many winter activities, it’s important to be aware of the hazards of winter weather, including lake-effect snow storms.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.