Space Industry Startups Eye Asteroid Mining, Tourism And In-Orbit Construction As The Future

SEATTLE -- For a long time, Rob Hoyt harbored a lonely obsession with space tethers. Few people outside of NASA and the military were willing to talk with him about it. There were certainly no investors answering his calls for 15 years after he started a company to build top-notch tethers, long cords that connect spacecraft or satellites while in orbit, and other space technologies. But lately, Tethers Unlimited, the company Hoyt founded in 1994, is gaining a whole new clientele and feeling the unfamiliar pressure of competition as more private companies than ever before aspire to make money in outer space.

“There are a lot more people working on space missions than five or 10 years ago,” he says from the company's headquarters in a nondescript business park in Bothell, Washington, just 20 miles north of downtown Seattle -- not exactly the sort of place one might imagine as the birthplace for a coming revolution. “It’s getting kind of fun.”

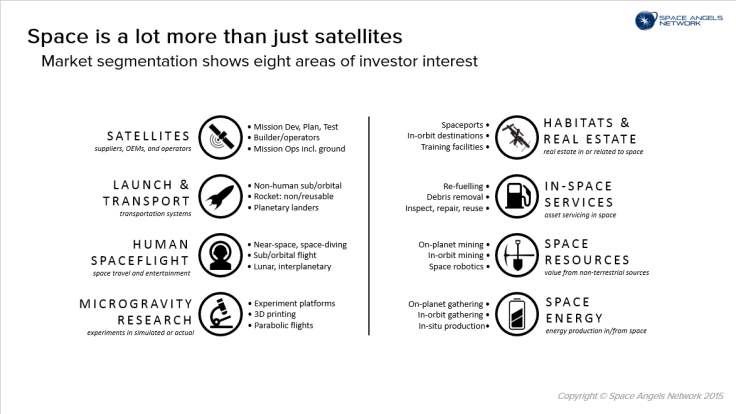

While Elon Musk's SpaceX and Sir Richard Branson's Virgin Galactic have set out a widely publicized vision for a second space age, dozens of lesser-known companies -- many of them in the Seattle area -- are pursuing ambitious projects of their own in the expanding space industry. Richard David, CEO of NewSpace Global, estimates that there are about 700 companies dedicated to commercial space worldwide -- up from 100 in 2011. They build rockets, offer mission planning services, pack freight into spaceships and monitor planetary risks.

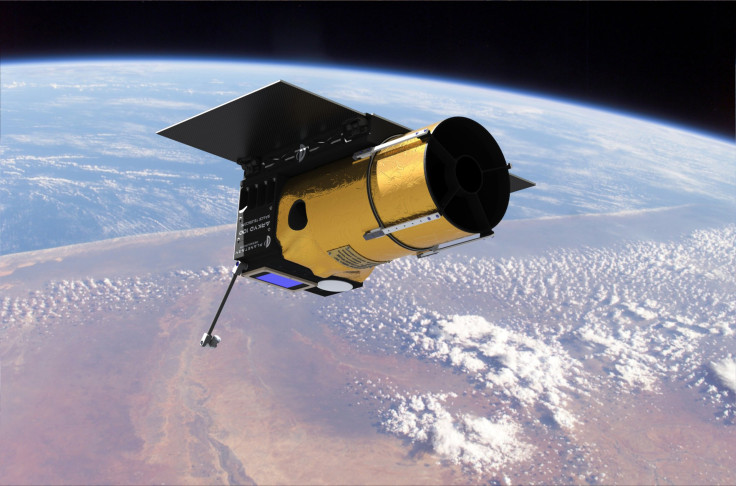

“People often think of this as a very long-term thing that is far in the future,” says Chris Lewicki, president and chief engineer of an asteroid mining company called Planetary Resources based in nearby Redmond. “I would encourage people to realize that it’s happening right now.”

Witnessing this, investors have begun to pour money into space-related pursuits, and the influx of funding has further galvanized the industry. Notable among them is Paul Allen, co-founder of Microsoft, who supported Mojave Aerospace Ventures, which won the $10 million Ansari X Prize in 2004 for being the first non-governmental entity to launch a sub-orbital spacecraft. Investors have sunk $10 billion into the private space industry over the past decade, and three-fourths of that money has come from venture capital funds and private equity firms, reports NewSpace Global.

The surge of interest and investment has inspired Congress to lay the groundwork for the new wave of space-based industries. The House recently passed the Space Act to permit companies to sell any resources they extract from asteroids in space – which Lewicki says isn’t so far off. The bill is now being reviewed by the Senate's Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation.

The grand ambitions of these startups and their backers are matched only by the magnitude of the political, technological and scientific hurdles that remain. Not least among these challenges is the fact that so many companies working on varying concepts are trying to get off the ground simultaneously, which makes it difficult for investors to discern which ones will truly lead the way forward.

“Space right now is where biotech was in the early '80s -- there’s a tremendous amount of innovation, but no one knows how to organize themselves,” says Richard Gayle, co-founder of the Space Trade Association. He spoke with cautious enthusiasm on the breezy patio of a corner restaurant in Bellevue, Washington, where a group of space enthusiasts met up for drinks after work last week to speculate on -- what else? -- the future.

Aiming For The Stars

The venue was a convenient place to start the discussion because as the space industry rapidly expands, Seattle area companies are the leading the charge: SpaceFlight Industries Inc. books extra cargo space on rockets at a minimum price of $295,000 per load; the space tourism company Blue Origin, founded by Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos, just tested a reusable spacecraft in April; and another company called Aerojet Rocketdyne has been building rockets in the area for 60 years and now boasts more than 500 employees.

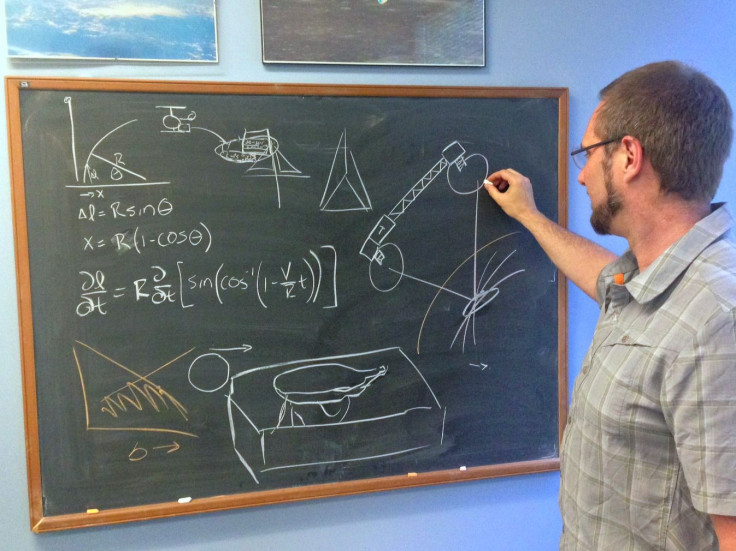

Back at Tethers Unlimited, Hoyt has moved beyond space tethers and is now betting on space-based factories. He says floating manufacturing plants will be particularly useful for making large pieces of infrastructure such as satellites, space stations and antennas, where “bigger is better.” The size of these components is currently limited by the size of a rocket that can launch them skyward.

Later this year, his team will launch a demo of SpiderFab, a system no larger than two loaves of bread that has shown it can manufacture a 50-meter truss from spools of carbon fiber in a lab here on Earth.

“Our long-term goal is the self-assembling satellite,” he says.

Planetary Resources, where Lewicki works, is another emerging leader with deep industry expertise. Before he joined the company, Lewicki helped to land three Mars rover missions as a flight director and mission manager for NASA. He saw the recent swell in the commercial space industry as an opportunity to follow his interests in the economic development of extraterrestrial resources.

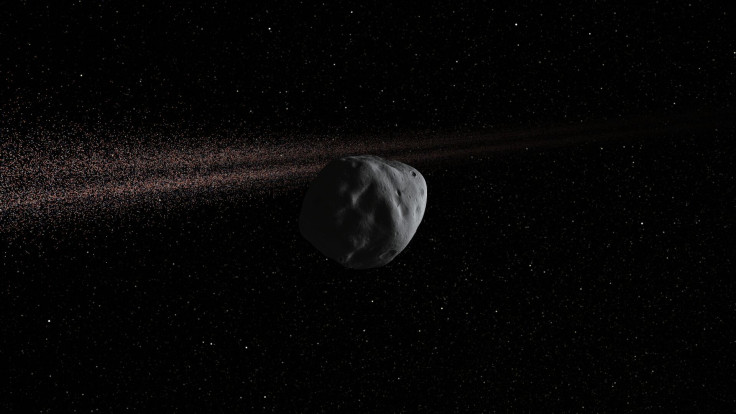

Now, Lewicki spends his days trying to figure out how to mine asteroids, which are packed with hydrogen, oxygen and metallic ore. Planetary Resources wants to use these raw materials to produce fuel for rockets and satellites which it will sell to companies and space agencies through refueling stations in orbit. Both the mining and filling operations would be manned by robots, and powered by the sun.

“Just like we set up gas stations all across the U.S., we can do the same thing in space,” Lewicki says.

His team is surveying nearby asteroids to find those likely to have the raw ingredients necessary to make fuel or produce other resources. One asteroid on the company's short list contains more platinum than has ever been found on all of Earth.

Planetary Resources, which is backed by Google co-founder Larry Page and Sir Richard Branson of Virgin Group, admits it will need to invent or improve a slew of technologies for better propulsion and communications long before it can open its first mine.

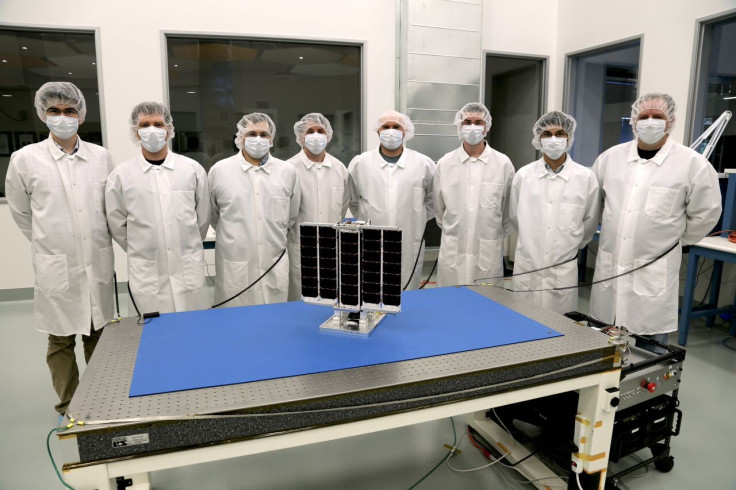

The team experienced a setback last year when its first demonstration satellite perished in a fiery explosion aboard a rocket destined for the International Space Station. Another version of the test satellite is set to launch from the space station in July.

Asteroid-Sized Challenges

Hoyt at Tethers Unlimited has also learned that the road forward into space entrepreneurship can be a rocky one. Not long after he started his company, he realized that there was not as much money in the pursuit of the perfect space tether as he had thought.

“If we had stayed focused only on space tethers, I’m fairly sure we’d be out of business,” he says.

Today, the company creates a wide range of products that solve common problems for NASA and military agencies as well as private companies -- such as a product called Terminator Tape that can produce enough drag to cause small satellites to fall back to Earth once their mission is complete. His company’s progression from early research and development to the testing and marketing of usable space technologies has been 20 years in the making.

In April, Tethers Unlimited landed a $750,000 NASA contract to work on a new challenge: find a way to turn the leftover bubble wrap and foam that is used to cushion experiments and equipment sent up in rockets to the International Space Station into a filament that astronauts can feed into an onboard 3D printer to make tools or radiation shielding.

Lately, Hoyt has also been able to sell more products to entities other than NASA. He spun off his knowledge of space tethers to create ties that keep underwater robots connected to ships for the U.S. Navy. He has also sold a self-guided anchor that was originally meant to help rovers climb out of crevasses to the U.S. Army, which will use it to hold temporary bridges in place.

“The market for technologies in space is still pretty limited,” he says. “You’re lucky to sell one or two of something. So we’re always looking for terrestrial applications.”

Hoyt admits to striking out a few times, too -- even though his company invented a net-like system to capture rogue asteroids or space debris and bring these hazards safely down to Earth, no one has placed an order for the service. “There isn’t a customer,” he says. “No one wants to have to pay for removing debris from space.”

Hoyt has sought outside funding only once in the company’s earliest days, without much success -- “As soon as I said ‘space,’ they were like, ‘No, thank you,’" he says.

But lately, investors have warmed to the idea of supporting space-related businesses, and fewer startups must rely so heavily on government funding. While NASA recently pledged $6.8 billion to pay Boeing and SpaceX to build a commercial spacecraft by 2017, many startups are looking elsewhere for funds. Planet Labs, a company that deploys low-orbit satellites to monitor agriculture, disaster response and urban planning, just raised $118 million in its third round of funding from a division of the World Bank.

“For a long time, NASA was a good customer, but I think the new companies are less focused on or not at all focused on NASA,” says Joe Landon, chief financial officer at Planetary Resources.

A High-Risk Game

Increasingly, companies are earning money from angel investors and venture capitalists who view space startups as a chance to get in on the ground level of a brand new industry with vast potential.

Don Weidner was persuaded to make an early investment in Planetary Resources after hearing a particularly convincing pitch by co-founder Peter Diamandis.

“He opened the books and showed me the projections and the spacecraft they're working on,” he says. “I even got to pick it up and be like, ‘Oh my god, this is the spaceship?’”

Weidner, who was formerly a supply chain manager at Intel, says he liked the fact that Diamandis and Lewicki didn't just have their sights set on mining asteroids, but also planned to make money in the short term by selling technologies and services to other companies and space agencies.

“Many of the things we're developing are actually useful for problems we have right here on Earth,” Lewicki says. He says the team is currently working with NASA to build a mapping tool that will scan the surface of the Earth in great detail, and which may someday survey an asteroid.

After backing Planetary Resources, Weidner became a member of the Seattle-based Space Angels Network, which is a global group of 65 investors started by Landon in 2006 who are interested in funding space startups. The group’s resume is stacked with scientific credentials -- the first 20 investors to join were all aerospace engineers. Even though most members still allot just a very small share of their wealth to space-related pursuits due to the inherent risks, members have so far made pledges ranging from $10,000 to several hundred thousand dollars to about two dozen startups.

Seattle’s Big Bet

Seattle companies are poised to lead the industry, so long as this funding lasts. While there is plenty of space-related activity in other aerospace hubs such as Southern California, Houston and Colorado, Landon says the reverberations feel especially strong here.

“With space, unlike a software company or an app company, you need to have both hardware and software expertise,” Landon says. “Seattle is a place where we have both.”

The city is home to a major research university (the University of Washington) and aeronautics prowess from a long history with Boeing. It’s also the headquarters for leading technology companies such as Microsoft and Amazon, with employees who can sometimes be persuaded to lend their programming skills to conquering space.

In fact, the technology sector in Seattle is undergoing a parallel revival that should only bring in more talent -- Facebook is opening a new office in the city, and Google has doubled the size of its Seattle-based staff over the past two years. Apple is steadily expanding its Seattle presence too, and SpaceX may hire up to 1,000 people for a new office that just opened here this month.

A Nod To The Future

Last year, the Space Angels Network brought new investors -- including Weidner -- to Los Angeles to scout out a cluster of space-related startups in Southern California; this year, the group will travel to Seattle.

Back at that first retreat in the Mojave Desert, Weidner could feel the potential in the air as he watched presentations by industry leaders.

“It felt like the garage days of the computer industry in the late '70s or early '80s where there were groups of 20 to 30 engineers and it looked kind of like a hobby,” he recalls.

Weidner favors an aggressive investment style, but he still says funding space is noticeably different from other commitments he has made in artificial intelligence, robotics and computing. While startups in those sectors often pitch on the hope that they will go public or be acquired, space-based businesses are more likely to remain private in the long run. About 70 percent of the world's commercial space businesses remain privately held, says Richard David of NewSpace Global.

“Space is more risk; it’s longer timelines,” Weidner says across the table from Landon at a Starbucks in Bellevue, just down the street from Landon's office.

Landon nods and acknowledges these investments may take a little longer to pay off -- five to seven years, he estimates, versus the typical three-to-five-year horizon that many investors feel is a sweet spot for returns.

Weidner perks up at the sound of that. “Really? I would have said five to 10, I don't know,” he says. “Seven would be great.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.