Spinrilla, DatPiff, My Mixtapez Apps Offer Illegal Access To Music, And Record Labels Won't Touch Them

If you found yourself worried about missing out on the Drake-Future mixtape “What a Time to Be Alive,” which dropped exclusively on Apple Music two weeks ago, you were not alone. And if you happened to be one of those people who illegally downloaded it using a mixtape app, you weren’t alone, either. According to a source at Universal Music Group who spoke on the condition of anonymity because he wasn’t authorized to discuss the matter, “What a Time to Be Alive” was illegally downloaded more than a million times in less than a week via Spinrilla and My Mixtapez -- two sites that are part of a subset of popular mixtape sites and apps that provide users with access to huge archives of amateur, occasionally illegal music for free.

Unlike on-demand streaming services like Spotify, which offer users access to millions of songs and albums, or radio-style services like Pandora, mixtape sites offer on-demand access to hip-hop mixtapes, compilations of unofficial or leaked material often built out of other artists' hit songs.

These sites and apps, many of which have been around for a decade, are an entrenched part of music consumption. According to data from App Annie, six of the 25 most popular music apps on iOS last month were mixtape apps, and some of the top sites, like DatPiff, have generated more than $1 million in annual advertising revenue. But they are also an intrinsic part of hip-hop's musical culture dating back decades, and they occupy a complicated place in record labels' worlds. Those labels and publishers -- which have found a way to monetize most of the music we can find online in one way or another -- don’t see a cent.

They also don’t want to talk about them, because a number of top hip-hop recording artists, including the aforementioned Drake and Future, regularly and routinely put their songs on these sites with their labels’ blessing. The major labels, however, all declined to comment on the relationship they have with these sites.

“It was one of those necessary evils,” said Shawn Prez, the head of Power Moves Inc. and the former vice president of promotions at Bad Boy Records. "Mixtapes were incredibly important to breaking artists."

Cultural Artifacts

The mixtape played a vital role in hip-hop’s cultural and economic history. In the late 1970s, when the art forms of rapping and DJing were growing up in parks and recreation centers in New York, people would trade recordings of DJ sets and people rhyming. In the 1980s, when club promoters were afraid of booking hip-hop acts or DJs, those same DJs would produce tapes in home studios and either give them away or sell them.

Later, DJs looking for new ways to stand out from the pack would cozy up to artist managers, producers and artists looking to get their hands on unreleased material that they could offer exclusively. DJ Clue, the first mixtape DJ to sign a major-label recording contract, would frequently hang around outside recording studios waiting for individual songs to be finished so he could release them before anyone else.

The tapes became so popular that they circled the globe. Copies of some of the most popular tapes, like Doo Wop’s “ ’95 Live,” made their way halfway around the world, showing up in collector hands in Japan and England and Brazil.

And as mixtape culture grew, the market for commercially released hip hop grew along with it. Label owners took notice. “The music industry embraced the mixtape DJ,” Prez said. “Those guys were essentially on the front lines of breaking our music.”

Legal Gray Area

The fact that every DJ was technically breaking the law was beside the point.

Irrespective of whether they sold their tapes or gave them away, mixtape DJs were all doing something illegal by distributing copyrighted material that they had not secured a license to distribute. “Whether you give it away or sell it, it's still a copyright violation,” said Robert Meloni, a partner at Meloni & McCaffrey, who represents a number of prominent artists, including Drake and Lana Del Rey.

Beyond the legal red tape associated with giving away songs that were somebody else’s property, plenty of hip-hop music, especially songs made in the genre’s earlier years, relies heavily on samples of pre-existing hits, which also needed to be cleared with rights holders legally. Those hip-hop tracks, all made by younger artists and producers who lacked the business know-how, resources or inclination to clear those samples, rarely did. “In most case, people don't get permission,” Meloni said.

But because mixtapes were unquestionably helping labels shift units, executives didn’t seem to mind. They began allocating resources to ensure their artists were well represented in that black market. “There was always a budget for mixtape promotion,” said Sommer Regan McCoy, founder of the Mixtape Museum and former manager of the Clipse. “Always.”

Before long, the label support for mixtape culture became even more institutional. Atlantic Records, home to artists like Curren$y, Wiz Khalifa and a number of other artists who put out mixtapes regularly, was one of the first sponsors of the Justo Mixtape Awards, the first awards show to recognize and celebrate the country’s most popular mixtapes, artists and producers.

Digital World

Inevitably, the world of mixtapes moved online. In 2004, the Boston DJ Clinton Sparks launched MixUnit, a site that became a kind of marketplace for mixtapes from all over the country. A year later, a site called DatPiff launched, and both businesses flourished. Five years after it went live, DatPiff's parent company, Idle Media, filed for an initial public offering.

But as piracy squeezed the music business, some labels began to change their tune. DatPiff was named in a number of lawsuits filed by artists for facilitating the distribution of songs that violated their copyrights, and in 2007, the Recording Industry Association of America went went to war with the mixtape industry, arresting popular mixtape DJs and producers Don Cannon and DJ Drama and jailing record store employees at shops that carried the tapes. While the RIAA is not currently in the middle of a full-scale offensive against these sites, their stance on them remains unchanged.

“Many mixtape sites and apps like these appear to operate under the misconception that they can distribute any content they choose to characterize as a mixtape and the burden is on the copyright owner to complain about each work. That is wrong,” Brad Buckles, the RIAA’s executive vice president of anti-piracy, wrote in an email. “These sites frequently engage in massive infringement of copyrighted works. They are unlicensed music services plain and simple and cannot hide behind the DMCA” -- the Digital Millennium Copyright Act.

Partners In Crime

Yet despite the widespread infringement and the lawsuits, the sites continued to operate, and artists, who saw the sites and apps as a proven place to grow their fan bases, continued to feed them. "Artists do what they want to do," McCoy said. "They'll leak to tapes. They're notorious for it."

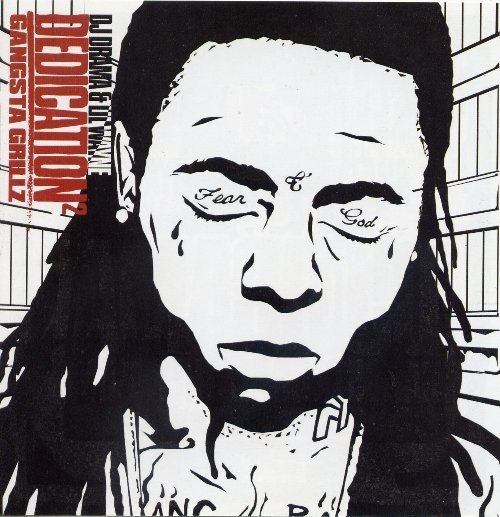

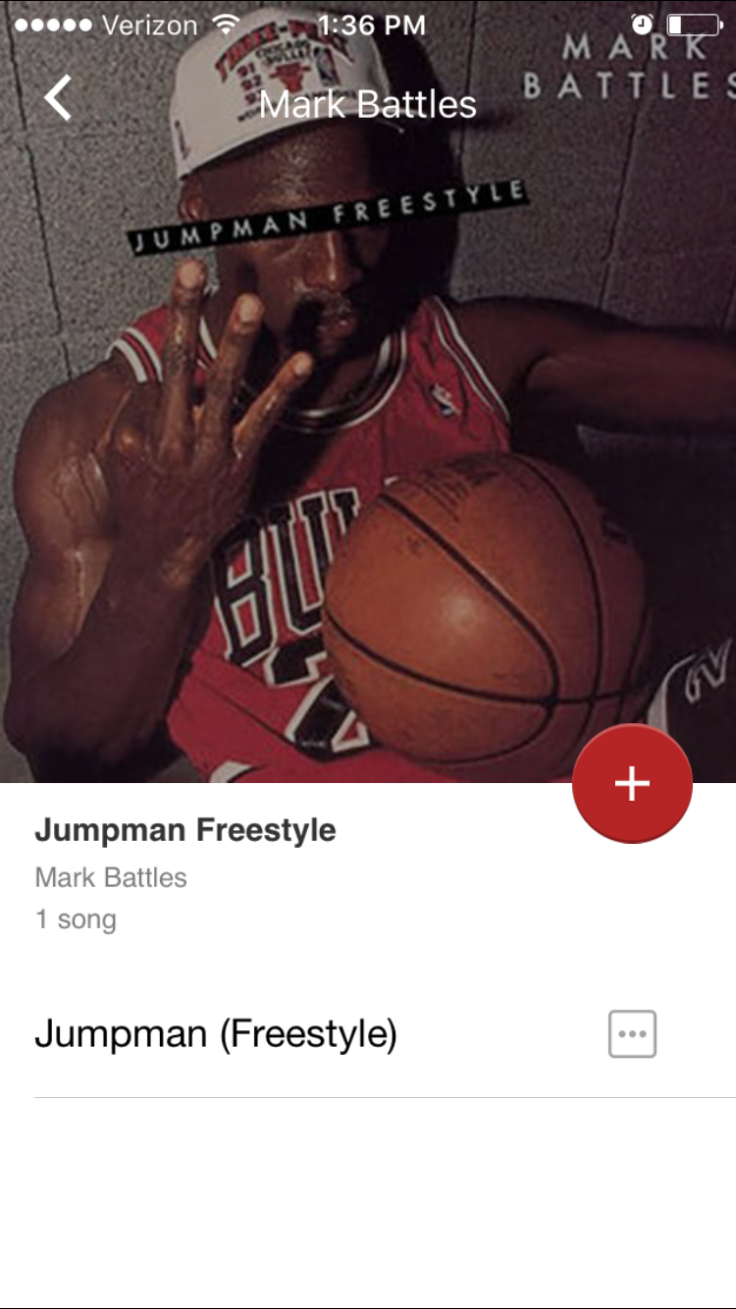

Thanks partly to the arrests and the suits, and partly to changing tastes, the mixtape and hip-hop evolved too. Producers moved away from blatant use of recognizable samples; mixtape DJs became more cautious in the material they used; and artists, following the example of stars including 50 Cent and Lil Wayne, started putting out album-length releases of original material and labeling them mixtapes. “Once upon a time, the mixtape was a playlist, a collage of old music, new music, all kinds of artists,” Prez said. “Nowadays, 90 percent of the mixtapes done are like artists dropping their own albums.”

Prez argues a large amount of the content that's filling sites like DatPiff and Spinrilla isn't owned by any of the labels that might once have rightfully felt infringed. But every once in a while, a release like Drake and Future's will pop up on one. And even if it doesn't, tracks featuring the beats or vocals from those hits will appear, often within days of the official release.

Yet despite the collaboration and interdependence, the prospect of an economic partnership feels stalled. Neither the three major labels nor Merlin, the digital rights agency that negotiates on behalf of independent labels, has any licenses in place with mixtape sites. According to a person with knowledge of the negotiations, Universal Music Group has tried to compel a number of the sites to sign a blanket licensing deal, though those talks were unsuccessful.

Similarly, the prospects of killing these sites in court are dim. "You cut off that one head, and 10 more pop up," Prez said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.