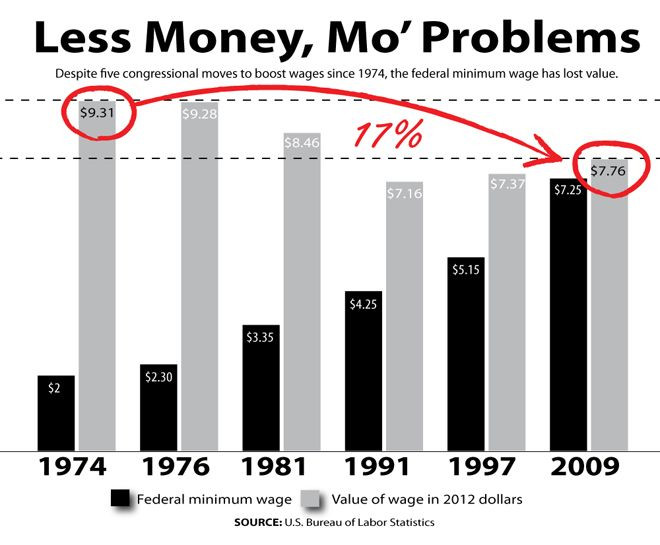

State of the Union 2013: Obama Calls For $9 Minimum Wage, Or Less Than What It Was In 1974 [PHOTO]

Way back in 1974, the year Nixon resigned, the federal minimum wage was $2 an hour.

How much would that wage rate be today in order to adjust for the rising cost of living we've seen in the past 39 years?

Answer: $9.31 an hour, or more than the $9 federal minimum hourly wage President Barack Obama called on Congress to pass during his State of the Union address. Included in his proposal: indexing future wage hikes to inflation, an attempt to stop the effect seen in the chart above.

We’ve come a long way since the early '70s, but one thing that hasn’t kept up is wages. And this has most hurt working Americans in lower income brackets who live paycheck to paycheck, where any fluctuation, such as the recent expiration of the two-year, 2 percent payroll tax relief plan, means much more than just canceling premium cable subscriptions.

Finding a happy place between paying hourly workers too little to keep up with price inflation and paying them too much, forcing businesses to lay off employees and freeze hiring, is a debate that in 75 years has never been completely resolved.

It’s a classic economic battle ... perhaps one of the most important affecting capitalism since the abolition of slavery and child labor, and the push to improve workplace safety in the developed world. These measures have increased the cost of doing business, but they're ones that most people agree is a cost that society is willing to pay, collectively, in higher prices.

Consider June 24, 1938.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt addressed the nation in one of his famous fireside chats, defending his push to ban child labor, and to set “a floor below wages and a ceiling over hours of labor.”

The following day he signed into law the Fair Labor Standards Act, which has been the key template for the evolution of the earning and paying relationship between employer and employee ever since.

Here's what Roosevelt had to say about opponents of his push to implement a 25 cents hourly minimum wage, equivalent to $4.07 in 2012 dollars:

“Do not let any calamity-howling executive with an income of $1,000 a day, who has been turning his employees over to the Government relief rolls in order to preserve his company's undistributed reserves, tell you -- using his stockholders' money to pay the postage for his personal opinions -- that a wage of $11 a week is going to have a disastrous effect on all American industry. Fortunately for business as a whole, and therefore for the nation, that type of executive is a rarity with whom most business executives heartily disagree.”

That paragraph is as applicable to the modern wage debate as it was back then, from claims that raising a wage floor destroys jobs and is bad for the lowest-paid workers who are the first to get laid off when cutbacks are made, to accusations that large companies reduce their operating expenses to the benefit of shareholders by paying so little to their bottom-tier employees that they’re forced to seek medical care from the government through Medicaid.

And in recent years there has been a surge in the minimum-wage "abolitionist" movement that argues having any minimum wage harms young, low-skilled workers. (Never mind that under current U.S. labor law, employees are legally allowed to pay a special minimum wage of $4.25 an hour for up to 90 days for workers under the age of 20.) Of course, this doesn't mean much to the growing number of professional interns who work for free.

It’s not likely that the debating points will change under Obama’s call to pass wage-increase legislation. His proposal to link the federal wage increase to the rising cost of living will definitely be met with Roosevelt’s “calamity-howling.”

But one point is not up for debate: Regardless of which side of the issue you stand on, wages have not kept up with America’s cost of living, making it more difficult for the working, taxpaying bottom-bracket earners in this country to pull themselves up by their proverbial bootstraps.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.