Study On Organic Poultry Hopes To Trigger A Wakeup Call For U.S. Regulators

With the recent salmonella scare and the upsurge in the price of corn against wheat in commodity trading, the health of U.S. livestock and subsequently, the health of the U.S. populace that consume these will largely depend on the feed used by poultry farmers.

Organic agriculture, long seen as the best foot forward for supporting good health has now found new proof in a recent study that expects to reduce existence of drug-resistant bacteria on U.S. farms that "go organic".

The study, published in Environmental Health Perspectives and led by Dr. Amy R. Sapkota of the University Of Maryland School Of Public Health, provides findings that states, "Poultry farms that have transitioned from conventional to organic practices and ceased using antibiotics have significantly lower levels of drug-resistant enterococci bacteria."

Inferring on her research, Dr Sapkota expects that reductions in drug-resistant bacteria on U.S. farms that "go organic" are likely to be more dramatic over time as reservoirs of resistant bacteria in the farm environment diminish.

This is the first research attempt to show lower levels of drug-resistant bacteria on newly organic farms in the U.S., suggesting that removing antibiotic use from large-scale U.S. poultry farms can result in immediate and significant reductions in antibiotic resistance for some bacteria.

The question that has long been raised is, when non-therapeutic antibiotics have long been banned from livestock farms across most of Europe; wouldn't it be beneficial for American regulators to re-think on the same lines? Banning antibiotics from breeding birds in American poultry farms could be an the alternative to curb bird flu and infections that keeping cropping up time and again. So, what are the salient features of the new study that could potentiate safe chicken farming?

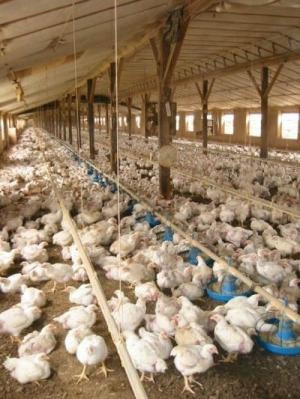

Dr Sapkota and team investigated the impact of removing antibiotics from U.S. poultry farms by studying ten conventional and ten newly organic large-scale poultry houses in the mid-Atlantic region. They tested for the presence of enterococci bacteria in poultry litter, feed, and water, and tested its resistance to 17 common antimicrobials.

Study findings noted, "While all farms tested positive for the presence of enterococci in poultry litter, feed, and water as expected, the newly organic farms were characterized by a significantly lower prevalence of antibiotic-resistant enterococci."

The researchers said, "Multi-drug resistant bacteria are of particular public health concern because they can be resistant to all available antibiotics, and are, therefore, very difficult to treat if contracted by an animal or human. Forty-two percent of Enterococcus faecalis from conventional farms were multi-drug resistant, compared to only 10 percent from newly organic farms, and 84 percent of Enterococcus faecium from conventional farms were multi-drug resistant compared to 17 percent of those from newly organic farms."

Dr Sapkota explained the reason behind tracking the enterococci bacteria saying, "We chose to study enterococci because these microorganisms are found in all poultry, including poultry on both organic and conventional farms. The enterococci are also notable opportunistic pathogens in human patients staying in hospitals. In addition, many of the antibiotics given in feed to farm animals are active against Gram-positive bacteria such as the enterococci. These features, along with their reputation of easily exchanging resistance genes with other bacteria, make enterococci a good model for studying the impact of changes in antibiotic use on farms."

Regarding future analysis of the study, Dr Sapkota added, "While we know that the dynamics of antibiotic resistance differ by bacterium and antibiotic, these findings show that, at least in the case of enterococci, we begin to reverse resistance on farms even among the first group of animals that are grown without antibiotics. Now we need to look forward and see what happens over 5 years, 10 years in time."

As reported by MarketWatch, poultry prices ticked higher margins in the second quarter this year; prices for boneless skinless breast meat averaged $1.34 a pound, down from $1.61 a year ago. Chicken wings were 77 cents a pound, compared to $1.23 a pound. The Georgia dock price for whole birds (a barometer of grocery-store demand) remained unchanged at 86.5 cents a pound.

In this light, Tyson Foods, one of the world's largest processors and marketers of chicken, beef and pork, as well as readymade foods, had commented on its chicken business saying that it is heading for a loss this quarter. Chief Executive Donnie Smith, Tyson said he is looking to lift contract prices for certain chicken products as feed-grain costs remain high amid tight U.S. corn supplies. He said, "We believe the current input costs are here to stay." "Therefore, we're focused on pricing because the current situation is simply unsustainable."

Under the current scenario, industry watchers anticipate another painful restructuring of the U.S. poultry market akin to the one that was brought about during the downturn of 2008.

With these in mind, would organic breeding be sustainable in the long run? This needs to be addressed by regulatory agencies that do have a say in this matter. Although government regulators such as the USDA and the FDA, have acknowledged the problem, along with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the efforts to minimise antibiotics in livestock feed has yet to be resolved on a daily basis.

The new study sure is a wakeup call in this direction!

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.