Super-Puffs: Hubble Observations Unravel Mystery Behind 'Cotton Candy' Planets

KEY POINTS

- 'Super-puffs' are young exoplanets with the density of cotton candy

- Researchers used the Hubble telescope to get a closer look at the super-puffs orbiting Kepler 51

- The super-puffs are so puffy that they may be just several times the size of Earth but look as massive as Jupiter

- Researchers were unable to have a closer look at the super-puffs' atmosphere because of a thick layer at high altitudes

- The planets are shedding gas at a rapid pace, so they can lose their "puffiness" in a billion years

The term “super-puffs” is the nickname used for a rare and unique class of young exoplanets that basically have the density of cotton candy. In fact, less than 15 super-puffs have so far been recorded in the galaxy.

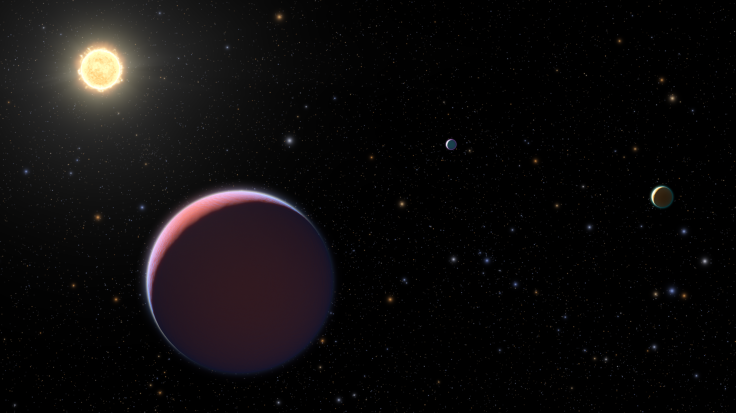

In 2012, three super-puffs were discovered to be orbiting around the young Sun-like star, Kepler 51, but it wasn’t until 2014 when astronomers discovered the exoplanets’ surprisingly low densities. To get a closer look at these mysterious cotton candy planets, the researchers of a new study that will appear in The Astronomical Journal used the Hubble space telescope to zoom in on the trio around Kepler 51 about 2,400 light-years away from the Earth.

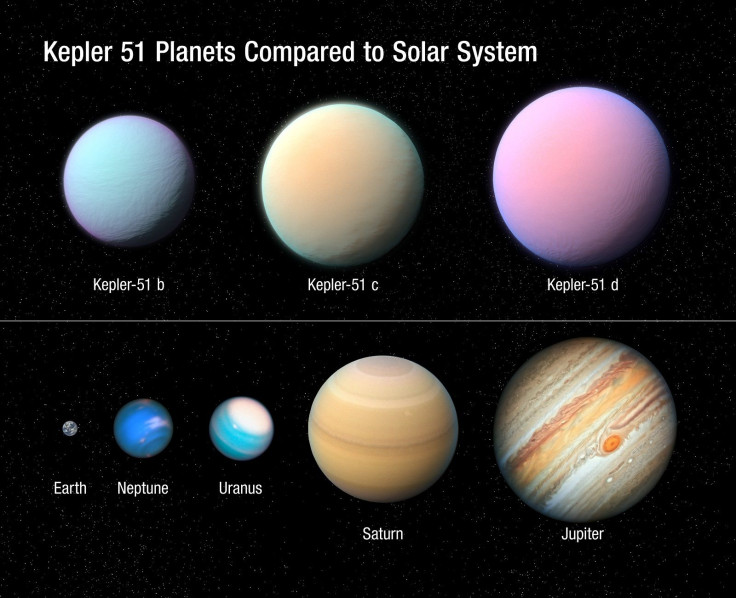

The team was able to refine the mass and density estimates of the planets, confirming that they are actually “puffy.” In fact, although the planets are no more than several times the size of the Earth, their atmospheres are so bloated that they look as big as Jupiter.

The researchers also attempted to look into the chemistry of the planets’ atmosphere, particularly for signs of water but they were surprised to find no telltale chemical signatures. Using computer simulations and other tools, the researchers surmised that the hydrogen and helium that make up most of the planet’s mass are actually clouded by thick clouds of particles high in their atmospheres. However, unlike the water-clouds on Earth, the cotton candy planets’ clouds may be primarily composed of photochemical hazes and salt crystals.

This is reminiscent of Saturn’s moon, Titan with its atmosphere cloaked by a thick, opaque layer at high altitudes, making it nearly impossible to look through.

“This was completely unexpected,” team member Jessica Libby-Roberts of the University of Colorado, Boulder said. “We had planned on observing large water absorption features, but they just weren't there. We were clouded out!”

The team also explored the possibility that the planets might not even be super-puffs at all, but instead, they found that one of the planets, Kepler-51 d was even less massive and puffier than previously thought.

The team concluded that it is possible that the planets’ puffiness might partly be due to the system’s relatively young age of 500 million years old compared to our Sun’s 4.6 billion years. Further, models also suggest that the planets were formed outside of their host star’s “snow line,” or the region where icy materials can survive, they migrated closer to their sun.

However, the researchers also observed that the unique exoplanets are actually shedding gas at a rapid pace. In fact, the planet closest to their host star is dumping an estimated tens of billions of tons of material into space per second. Should the trend continue, the planets could significantly shrink within a billion years, thereby losing their puffiness.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.