Supermassive Black Hole Binary Photobombs Andromeda Galaxy, Tightest Pair Ever Seen

While looking for an unusual star in the nearby Andromeda galaxy, astronomers instead found a pair of supermassive black holes. The binary system is the most closely orbiting pair of black holes of their kind we have ever seen.

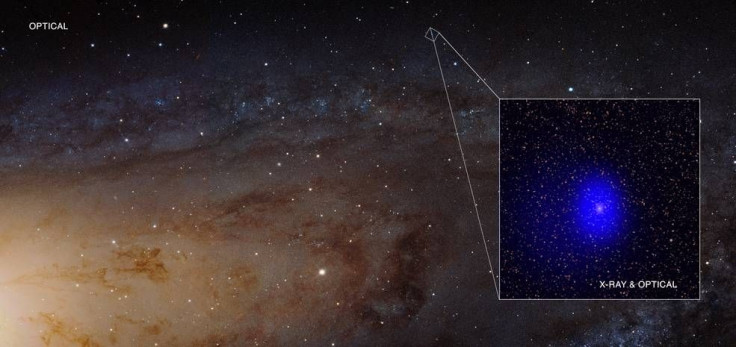

In a statement Thursday, NASA ascribed the finding to the black holes photobombing images of Andromeda (also called M31, after its position in the Messier catalog of non-cometary objects) that were taken by the agency’s Chandra X-ray Observatory, as well as optical data collected from Earth-based telescopes in Hawaii and California.

Trevor Dorn-Wallenstein of the University of Washington in Seattle, who led the paper describing this discovery, said in the statement: “We were looking for a special type of star in M31 and thought we had found one. We were surprised and excited to find something far stranger!”

Together, the two supermassive black holes have a mass of about 200 million times that of the sun, and are located about 2.6 billion light-years from Earth. The binary system is called LGGS J004527.30+413254.3, or J0045+41 for short.

Earlier observations of periodic variations in optical light from J0045+41 led researchers at the time to classify it as a pair of stars orbiting each other every 80 days. But Chandra’s X-ray data, collected later, was far more intense than what a pair of orbiting stars would produce, leading Dorn-Wallenstein and his team to look for a different kind of binary system — one that contained a neutron star or black hole.

But that would have satisfied as an answer only if J0045+41 was located inside M31. Instead, a spectrum from the Hawaii-based Gemini-North telescope showed that at least one of the objects inside J0045+41 must be a supermassive black hole, and that allowed scientists to estimate its distance, which turned out to be far beyond the 2.5 million light-years away where Andromeda is.

The spectrum also suggested the possible presence of another black hole inside J0045+41, one that was moving at a different speed than the first, which is usually the case when two black holes are orbiting each other. The Palomar Transient Factory in California was used to look for periodic variations in the light from this unusual source, and the findings matched theoretical models of two huge black holes in orbit around each other.

This does not mean that J0045+41 definitely contains two orbiting supermassive black holes, but according to Emily Levesque of the University of Washington, a coauthor of the paper: “This is the first time such strong evidence has been found for a pair of orbiting giant black holes.”

The system could have formed billions of years ago, when two galaxies, each with a supermassive black hole in its center, collided and merged. The two supermassive black holes are currently estimated to be separated by a distance of less than a hundredth of a light-year.

“We’re unable to pinpoint exactly how much mass each of these black holes contains. Depending on that, we think this pair will collide and merge into one black hole in as little as 350 years or as much as 360,000 years,” study coauthor John Ruan, also of the University of Washington, said in the statement.

If everything is exactly as the astronomers predict in this study, the merger of these supermassive black holes will also emit gravitational waves, or ripples in the fabric of space-time. But those waves would be far stronger than the ones we have detected so far, and their far lower frequency would mean existing methods to detect gravitational waves (think LIGO and Virgo) won’t be able to spot them at all. Instead, we would need to use arrays of pulsars — a special kind of neutron star — to detect them.

“Supermassive black hole mergers occur in slow motion compared to stellar-mass black holes”, Dorn-Wallenstein said. “The much slower changes in the gravitational waves from a system like J0045+41 can be best detected by a different type of gravitational wave facility called a Pulsar Timing Array.”

Here is a video looking at J0045+41 in M31.

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/L640y7kYP9g" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe>

The paper, titled “A Mote in Andromeda's Disk: A Misidentified Periodic AGN behind M31,” appeared Nov. 20 in the Astrophysical Journal. It is also available on the preprint server arXiv.

This article has been updated with new information.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.