Supreme Court Rules Against EPA Mercury And Air Toxics Standards For US Coal Plants

Dealing a blow to the White House's efforts to curb pollution, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled Monday the Obama administration acted improperly when it decided to regulate power plant emissions of mercury and other toxic air pollutants. The court’s 5-4 decision will require the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to review and reanalyze landmark standards, which took effect in April, and consider the costs the regulations will impose on power producers.

At issue in Utility Air Regulatory Group v. EPA is whether the environmental agency properly considered industry-compliance costs when deciding to adopt the rules -- or if regulators instead unfairly emphasized the public health benefits. The EPA’s Mercury and Air Toxic Standards, adopted in 2012, aim to curb power-plant pollution by 75 percent by forcing utilities to install and operate equipment that removes mercury and fine particulate matter.

"The Agency must consider cost—including, most importantly, cost of compliance—before deciding whether regulation is appropriate and necessary," Justice Antonin Scalia wrote for the majority.

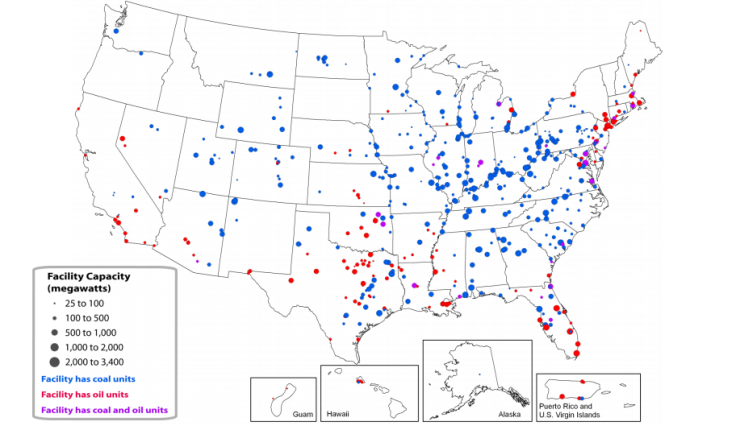

Across the county, hundreds of power plants spew toxic pollutants into the air, which settle on soil and in lakes and streams, gradually rising through the food chain. Mercury is particularly dangerous to pregnant or nursing women -- who can pass the toxin on to their unborn and newborn babies -- and to young children whose brains are still developing. Coal-burning plants account for about one-half of all U.S. mercury emissions, the EPA estimates.

The Supreme Court verdict reverses an earlier decision by a federal appeals court.

The D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals in April 2014 rejected a challenge to the rule, saying it found the EPA’s designation of mercury emissions from power plants as a “threat to the public and the environment” substantially and procedurally valid. The Utility Air Regulatory Group, the National Mining Association and 21 U.S. states appealed that ruling, arguing the EPA should have considered the cost of regulations.

Opponents of the court’s decision lamented the loss of environmental protection standards. “The court's decision to let polluters off the hook is a huge setback for our kids' health,” said Environment America’s Anna Aurilio. "But we'll keep fighting for clean air and a healthier future. Polluters' days of dumping unlimited deadly toxins into our air are numbered."

About 600 power plants are affected by the EPA’s mercury rules -- many of which have already made the necessary changes and upgrades to comply with the standards. Other operators have found that shuttering coal-fired power units is cheaper than installing the necessary equipment, especially given the fierce competition from cheaper natural gas in recent years.

While shuttered plants will remain retired, some of the 173 units that applied for an extension from the EPA until next April may be allowed to operate longer, experts say. The court reversed the D.C. Circuit court decision and sent the case back to the lower court to be redecided. This will give the EPA a chance to evaluate the decision and rework the rules.

Some legal experts say the Supreme Court’s decision could set a precedent for any future case over the EPA’s proposed Clean Power Plan, another hotly contested environmental policy that would force states to reduce carbon dioxide emission from existing facilities.

The Obama administration is expected to finalize the standards this summer, after which major U.S. coal companies and coal-producing states are expected to file a lawsuit. Coal mining giant Murray Energy and 14 states sued the EPA last year after the agency proposed the rules, but the D.C. Circuit appeals court tossed out the challenge, saying it was unprecedented for a court to review a draft rule.

But Brendan Collins, a law partner at Ballard Spahr LLD and lead environmental litigator, said he doesn’t think the Supreme Court’s decision on mercury rules will have much bearing on the Clean Power Plan’s legal standing. Collins represents a group of power companies that intervened in the Supreme Court case in support of EPA’s mercury rules.

“The [mercury] decision will leave tea leaves in the bottom of the cup that people will try to read,” he said. But the mercury rule is about whether EPA properly considered costs and used appropriate decision-making criteria. Opponents of the EPA’s carbon rules will likely raise questions the agency’s authority to impose the measures in the first place. The mercury case “is not at all about the scope of EPA’s authority,” he said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.