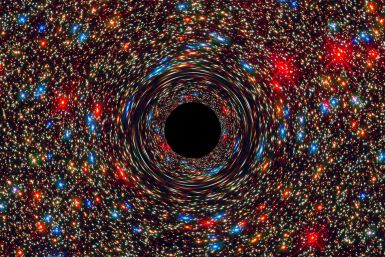

A new computer model has finally solved a longstanding cosmic quandary — how did supermassive black holes form in the first billion years of the universe?

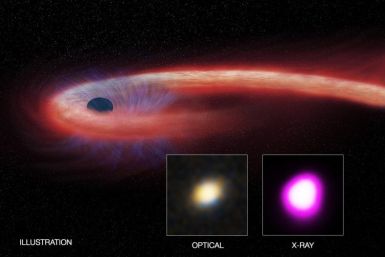

A team of astronomers has spotted a supermassive black hole located in a galaxy 300 million light-years from Earth "choking" on stardust.

How they grew to their size at a time when the universe was relatively very young — less than 800 million years old — has been a mystery ever since they were found.

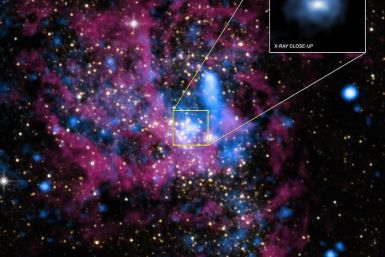

Analysis of gigantic gas bubbles burped out by Sagittarius A* — the black hole at the center of our galaxy — has revealed when it ate its last big meal.

A new survey of over 90,000 radio galaxies has identified 1,500 compact galaxies — some of which may never "grow up."

A team of scientists detected temperature swings in ultrafast “burps” of hot winds emitted by a black hole's accretion disk. These outflows could be responsible for preventing the birth of stars.

New evidence suggests that a black hole of roughly 2,200 solar masses is hiding in the center of a globular star cluster 13,000 light-years from Earth.

Numerous tidal disruption events have been observed by astronomers in the past, but they usually lasted only about one year or so.

The black hole, found lurking about 10,000 light-years away in the gas cloud of the supernova remnant W44, is believed to be just one of the millions peppered throughout our cosmic neighborhood.

The information paradox has been vexing scientists since the 1970s, when Stephen Hawking discovered that all black holes eventually evaporate, completely erasing all information about whatever they gobbled up in the past.

The two discoveries, from galaxies relatively close to the Milky Way, were made using a NASA instrument that can detect X-rays.

The Imaging X-ray Polarimetry Explorer mission, to be launched in 2020, would use three space telescopes equipped with cameras capable of measuring the polarization of high-energy X-ray radiation.

The computer model tracks the path of individual particles in the accretion disk plasma around the supermassive black hole, instead of treating its motion as a macroscopic fluid.

The number of known black holes is expected to double in the next couple of years thanks to a new detection method.

“The Copernicus Complex” author Caleb Scharf has revealed which type of black hole is more dangerous to man.

According to a new study, jets of energetic plasma emerging from a black hole’s accretion disk can increase turbulence of gas and dust in a galaxy, thereby preventing star formation.

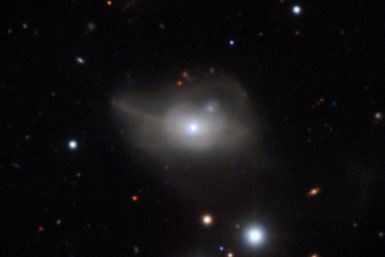

Scientists believe that the black hole, named XJ1417+52, may originally have been at the center of a distant galaxy that merged with a larger one.

The dual-star system is “the first gamma-ray binary in another galaxy and the most luminous one ever seen,” NASA said in a statement Thursday.

For the first time ever, scientists have observed, in infrared radiation, "tidal disruption" flares emitted by black holes after devouring stars.

The galaxy, 555 million light-years from Earth, is exhibiting atypical variations in its brightness — a phenomenon scientists attribute to two dueling supermassive black holes.

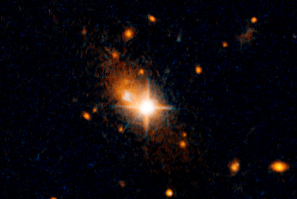

The 63 newly-discovered quasars, all of which date back to when the universe was just one billion years old, may shed light on the formative years of the cosmos.

Stephen Hawking had proposed in the 1970s that black holes can radiate quantum particles that would lead to their eventual evaporation.