Teaching Islam In Public Schools: Why Fear Of Religious Education Underscores The Need For It

During the first week of his world religions class at Texas State University, religious studies Professor Joseph Laycock shows his students a slide of how McDonald’s, which serves customers in 119 countries, offers different menu items in different parts of the world. In Israel, the Golden Arches don’t serve cheeseburgers. In India, veggie burgers are on the menu. And in Indonesia, McDonald’s makes sure its customers know that the beef they serve is halal. The variations are all due to the religious dietary restrictions in those countries.

“Knowing about world religions isn’t some kind of multiculturalism thing,” says Laycock, who has also taught high school students. “McDonald’s is all about the bottom line. They need to know about the religions of their customers. It’s a practical thing.”

Laycock’s slides underscore to his students that, in a shrinking world, an awareness of the religious beliefs of the people around the world is a necessity.

But not everyone shares his view. Stories of parents complaining about their children learning about Islam in social studies and history classes have made news in recent weeks. In Tennessee, a state lawmaker has introduced a bill banning the study of religion until 10th grade, arguing against “indoctrination,” after parents complained about public school curriculum that taught about Islam.

But experts say that the fear of religious education is misplaced, and the concerns that some parents are raising demonstrate precisely why Americans need to be better educated both about various religions and what is allowed in public schools.

“There are societal and educational reasons for learning about the world’s religions,” says Linda K. Wertheimer, author of “Faith Ed: Teaching About Religion in an Age of Intolerance.” “It makes it easier to understand history. It helps you understand the crises going on in our world, both past and present. But it also helps us understand the people in our community.”

Teaching Is Not Preaching

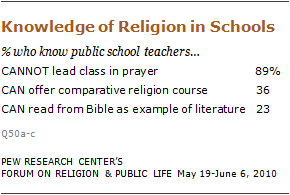

Wertheimer adds that most Americans are not well-informed about religious literacy, and they are often confused about the difference between teaching and preaching in public schools. A 2010 Pew Research Center Survey indicates that, on average, Americans scored 50 percent on basic religious literacy tests. And there is widespread confusion over what is allowed in public schools when it comes to religion.

Nine out of 10 Americans know, for example, that teachers can’t lead prayer in public schools. But only 36 percent of Americans believed that comparative religion could be taught in public schools, while two-thirds didn’t know that the Bible can be used in curriculum as an example of literature.

“We need to become constitutionally literate before we can become religiously literate. There’s a difference between proselytizing and teaching,” said Laycock, who added that it’s not just parents who have a misunderstanding of the establishment clause -- it’s teachers and administrators, as well.

“The separation of church and state is often misrepresented and misunderstood by citizens generally and by teachers in particular,” says Diane Moore, director of Harvard’s Religious Literacy Project, which provides resources and training on religion for journalists, educators and others. “They think we can’t teach about religion. That’s not true. What we can’t do is promote a particular religious conviction.”

It’s this chicken-and-egg dilemma that makes it difficult for some districts to help parents understand that religious education -- which has been part of most states’ history curriculum for years -- is different from preaching to students.

“There’s also absolutely no proof that teaching someone academically about a religion leads to indoctrination,” says Wertheimer.

Sherry McIntyre, a teacher at Johansen High School in Modesto, California, agrees. McIntyre teaches a world religions course to freshmen that has been a requirement of graduation for all high school students in Modesto City Schools. The Modesto school board adopted the curriculum 16 years ago and is the only school district in the country that makes such education mandatory. The one-semester course covers the basics of the world’s major religions but starts with a discussion of the First Amendment and an understanding of the separation of church and state.

“There’s a difference between teaching and preaching -- that’s our mantra. Not including religion in public school education is a disservice -- how do you explain why the Pilgrims came here, the mission system in California, the European wars? You have to know the basics,” says McIntyre, who has never fielded complaints from parents or students about the subject matter.

But Moore says religion is not something to be taught in a vacuum. She has helped develop the American Academy of Religion’s guidelines for teaching about religion in K-12 public schools. Simply teaching religious doctrine, says Moore, should be part of the approach but not the only one.

“If that’s the only way people learn about religion, you reinforce that it’s only about private practice and ritual,” says Moore. “We try to give teachers and students the tools to understand how religion functions in contemporary experiences. You can’t teach religion as an isolated unit. It’s the same as if you taught American history and then just spent a week on women in American history. We need to help people understand and recognize that religion is deeply influential. It’s a challenging thing.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.