Tesla Motors (TSLA) Is Showing A Broadening Gap Between GAAP And Non-GAAP As It Bets On Future Sale Of Post-Lease, Used Model S Sedans

Tesla Motors Inc. (NASDAQ:TSLA) is showing a widening gap between generally accepted accounting numbers and its "adjusted" figures. The little California electric carmaker with big aspirations could face a federal securities law claim over the way it has been massaging its accounting numbers since its second quarter, but even absent legal challenges, investors should pay closer attention to some of Tesla's non-GAAP accounting moving forward.

“We are investigating potential federal securities law claims against officers and directors of Tesla Motors Inc. (Tesla) (NASDAQ:TSLA) in connection with alleged violations by Tesla of Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) rules governing the disclosure of financial metrics that do not comply with Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP),” the New York City law firm Wohl & Fruchter said in a statement Monday.

Securities lawsuits are common when stock prices start to plummet, as TSLA has -- by 31 percent since the Oct. 1 Model S fire in Kent, Wash., that became a harbinger to two more fires and a disappointing third quarter earnings report. The report itself became the target on Friday of a takedown by Bloomberg View columnist Jonathan Weil, who said the way Tesla reported its 3Q non-GAAP numbers "seems to fly in the face" of SEC rules. All of this has been terrible news for a stock that has been riding an equity bubble for months. Since the Nov. 5 earnings report, two insiders exercised their compensation options to the tune of more than $12 million worth of TSLA. On Tuesday, Tesla stock was starting at a four-month low of $121.58, but it was still up 32 percent from six months ago as the bubble began to inflate.

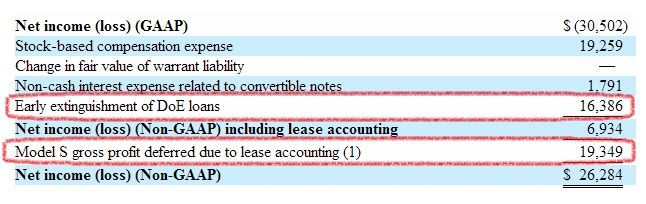

Tesla has been reporting two different financial metrics in its earnings reports: the one it's required to provide by law, the GAAP, and the adjusted earnings, often used by companies to account for one-time hits to their quarterly balance sheets, such as settling a lawsuit, opening or closing a factory, or paying off a loan early and booking the savings on interest, as Tesla did in its second quarter when it paid off its $465 million Department of Energy loan nine years ahead of schedule. The purpose of non-GAAP, companies say, is to impress on investors that these one-time hits are hiding underlying, organic real value that will be reflected in future quarterly results. Fund investors in particular tend to eschew non-GAAP numbers and focus on the GAAP.

While it’s legal for companies to release their own accounting methodologies, SEC rules require companies to provide GAAP figures and to explain to investors the differences. For insomniacs: here’s a breakdown of the rules for disclosing GAAP and non-GAAP accounting numbers.

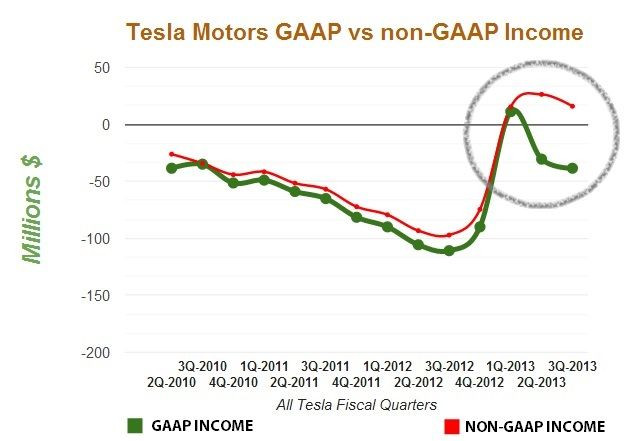

As the chart at the top of this story shows, Tesla has been puttering along quarter by quarter deeper and deeper into the red, from 2010, when the company went public, to the end of 2012. The company has been investing heavily in research and development, in building its manufacturing platform, in establishing a complicated supply chain and, most recently, in fleshing out its fast-charger networks and expanding its global sales network. Building a car company from scratch is a capital-intensive venture in ways making a mobile app will never be.

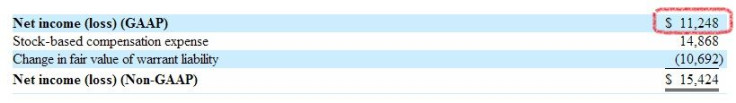

But since the company’s second quarter, the GAAP (the green line) and the non-GAAP (the red line) net income have been diverging, with the GAAP showing a loss while the non-GAAP shows a gain. Until 2013, Tesla’s main non-GAAP method of improving its balance sheet every quarter has been to return charges for stock-based compensation into its balance sheet, a controversial accounting method that was invented by the tech industry to lure executives with promises of future stock gains. Companies give them options to buy stock at a set price and executives can buy the stock anytime after it hits a certain level, known as the strike price. Stephen Jurvetson, a Tesla board member, did this last week, allowing Tesla to book about $1.5 million in "revenue" over the $9.53 million Jurvetson made from the deal.

In the second quarter, Tesla began an even more controversial accounting practice linked to its resale value guarantee for customers who lease its vehicles. What it boils down to is this: Tesla guarantees to buy back leased Model S sedans between 36 and 39 months old for 50 percent of the value of a 60 kWh Model S, and 43 percent of the value of any upgrades. Then it plans to make money from these cars, and reports that money as deferred gross profit. Accountants say tsk-tsk, that you can't do that under GAAP.

“As far as I can tell Tesla is accounting for the resale value guarantee assuming that the vehicles will be worth that amount when the guarantee is delivered on,” Ian Gow, assistant professor of business administration at Harvard Business School, wrote in an email to International Business Times. “Given the likely rapid development of electric vehicle technology in the next three years, assuming that three-year-old Teslas will sell for more than comparable BMWs and Lexuses seems ambitious.”

So investors should watch this closely to see how much Tesla books every quarter as money it expects to recover. The answer to the question is this: How much will you pay for a three-year-old Model S later on down the road?

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.