There will be no New Gold Standard, Part II

There are huge commercials all day long: 'Cash for gold, cash for gold'. Ever since gold went up...at least three times a day, we have customers asking about melting pieces. We try to save them from the melting pot.

So says Tobina Kahn, vice-president of US heirloom-jewelry business House of Kahn. There's so much good antique jewellery being lost, chips in Claude Morady, a jewelry boutique owner in Beverly Hills, also complaining to theFinancial Times. Lots of nice things are being melted down.

Melted down for what? For gold investment, of course! The pace of physical monetization - the rate at which scrap and newly mined gold is turned into bar and coin - hasn't been this frantic since 1980. Back then, jewelers and auctioneers also pleaded with the public to stop scrapping fine art at the smelters. Back then, higher prices led to a surge in thefts of silverware too, just as the UK's Ministry of Defence has recently suffered. And back then, the root cause was the very same as well.

[Raising rates is] the wrong policy, for the wrong reason, at the wrong time

- Gerard Lyons, chief economist at Standard Chartered

Although I acknowledge that the ultimate destination will be considerably higher double-digit inflation 5-10 years from now...I side with the belief that virtually all of the components of rapidly rising inflation are outside [central] banks' control.

- Albert Edwards, strategist at Societe Generale

Low real rates - let alone the negative real rates that sometimes occur - are extremely unpopular with millions of people, not merely top-hatted financiers...[but raising UK rates now] would risk a businessmen's riot in Downing Street...

- Samuel Brittan, FT columnist since 1966

Yes indeed! Real US interest rates now stand at minus 2.0%, even on the official measure of inflation. ShadowStats' application of '70s-style mathematics would put the number nearer 9.5% below zero. Here in the UK, real interest rates now stand at minus 5.0% per year, the worst since 1977, when double-digit inflation made the destruction of money all too livid (and gold prices rose very much faster). Even in the austere and ever vigilant Eurozone, this week's rate hike - so disparaged by the experts above - took nominal rates to just 1.25% remember. That's less than half the 17-nation currency zone's inflation rate for March.

Any wonder that gold and silver prices have jumped? The last time the world imposed such deleterious rates of interest on that risk-averse class of mugs called cash savers was the late 1970s. Back then, the idea of a return to some form of Gold Standard (or gold-and-silver standard) also gained currency. It even made it into Congress, which ordered a Gold Commission to consider the matter, which then reported in 1982. Scarcely a decade after formally abandoning the system, however, the Commission found no need for the US to revive its Gold Standard. Mostly because, by then, the inflation driving people to buy gold and silver - and so in turn driving economic policy-makers to consider the matter - was already subsiding, and subsiding thanks to the very thing which a Gold Standard would have brought about.

No, not gold as money. The Gold Standard never meant that. What defended the value of money - and thus savings - was higher interest rates...

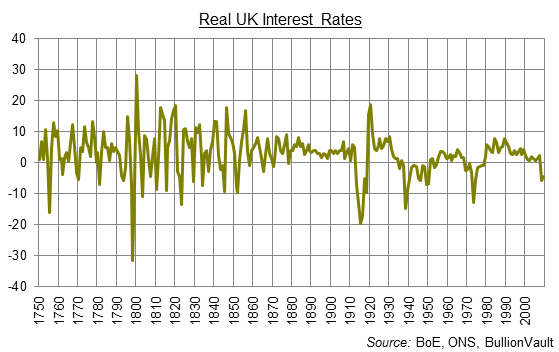

You can see Great Britain fumbling towards its classical Gold Standard - and then fighting to regain it, before quitting gold for good (or worse) - quite clearly on our chart. It maps the real rate of interest, after accounting for domestic UK price inflation, between 1750 and today.

Holding cash was generally a winning position, net-net, provided the country wasn't at war (and so hadn't suspended the government's promise to buy and sell bullion at the fixed price of £3 17s 10½d per ounce). Prior to quitting the Gold Standard in 1931, in fact, the average real return paid to bank savings was more than 3.6%. During the height of the global Gold Standard, interest rates averaged 4.0% above changes in the cost of living - which itself, and not by accident, in fact averaged zero.

[It] was a remarkable period in world economic history. It was characterized by rapid economic growth, the free flow of labor and capital across political borders, virtually free trade and, in general, world peace.

No, not a description of the Great Moderation so beloved of current Fed chairman Ben Bernanke, even though - minus the strong real returns to cash -n it fits pretty well. The period was from 1880 to 1914, known as the heyday of the Gold Standard, and the description comes from Michael Bordo, now professor of economics at Rutgers University, then writing for the St.Louis Fed in 1981.

Was the Gold Standard to thank for such felicitous economic conditions? British prime minister Benjamin Disraeli thought not. Our Gold Standard is not the cause but the consequence of our commercial prosperity... he told a gathering of Glasgow industrialists in the mid 1870s. Promising to buy and sell gold at that fixed price of £3 17s 10½d per ounce wasn't the cause of strong real returns to cash, either - but the result of it.

Whenever Great Britain faced a balance-of-payments deficit [i.e. trade deficit] and the Bank of England saw its gold reserves declining [as the Pound fell in value and so cash-owners swapped paper for metal], it raised 'bank rate', explains Bordo. [This] led to a reduction in overall domestic spending an a fall in the [consumer] price level. At the same time, the rise in bank rate would stem any short-term capital outflow and attract short-term funds [i.e.gold bullion] from abroad.

Which is the very simplest reason why there isn't a prayer for any kind of Gold Standard any time soon. Because backing money with gold isn't the problem for the legion of policy-makers and economists running the official monetary system. Raising interest rates is.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.