These Men Are Serving Life Sentences In Prison For Selling Pot

Fifteen years ago, Beth Curtis’ brother, John, was sentenced to die in prison.

His crime?

Selling weed.

In 1994, John Knock was indicted by the Northern District of Florida. Prosecutors alleged that Knock, then 47 years old, conspired to import vast amounts of marijuana into the United States through Canada over several years.

At the time of his arrest, Knock was a first-time offender. He had no history of being violent. Still, when Knock was convicted at trial, he was handed two life sentences, plus 20 years in prison. His extreme sentence was largely the result of drug laws passed in the 1980s, as well as so-called sentencing "enhancements" that can increase sentence length based on the type and quantity of drugs. (The Drug Enforcement Administration also labels marijuana as a “Schedule I” substance, which the agency classifies as “the most dangerous” type of drug.)

Beth Curtis admits that her brother did indeed import, at huge profits, an “extraordinary” amount of marijuana over the years -- hundreds, if not thousands, of pounds. But Curtis also doesn’t believe her brother deserves to spend the rest of his life behind bars for transacting in a drug that is now legal in several parts of the country.

"It’s illogical," Curtis says. "I don't think any nonviolent drug offender should receive a life sentence. I think it's a serious criminal justice problem."

President Obama would seem to agree.

Presidential Pardons

On Thursday, Obama will visit the El Reno Correctional Institution, a medium-security state prison in Oklahoma that houses 1,300 federal inmates. The visit, which is intended to showcase the president's larger desire to reform the criminal justice system, comes two days after Obama publicly commuted the sentences of 46 nonviolent drug offenders. (A commutation is the lessening or elimination of a penalty but not the nullification of the conviction; a pardon is both the cancellation of a penalty and the nullification of the conviction.)

"We spend $80 billion a year incarcerating people, who, oftentimes, have only been engaged in nonviolent drug offenses," Obama said in a video Tuesday. "I believe that, at its heart, America is a nation of second chances. And I believe these folks deserve their second chance."'

It is no secret that the United States has become the world’s leading jailer, surpassing incarceration rates of countries like Russia, China and Rwanda by vast margins. America makes up 5 percent of the world’s population -- but incarcerates 25 percent of the world’s prison population.

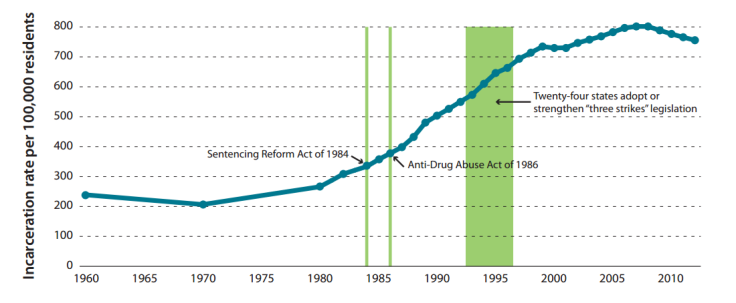

Pretty much all experts agree that the country’s extreme incarceration rates have been driven primarily by 1980s-era “three strike” laws and mandatory minimum sentences targeted at drug offenders.

The statistics are indeed fairly staggering: Beginning in 1980, when the U.S. began imposing harsher sentences for drug offenses, the number of prisoners in jail or prison for drug offenses skyrocketed by a factor of 10, surging from 40,900 inmates to 489,000.

As of May 2015, drug-related offenses account for 49 percent of the federal prison population, according to statistics from the Bureau of Prisons.

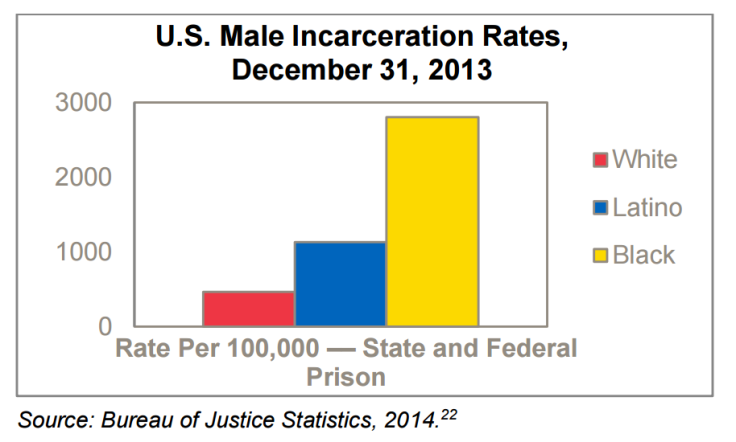

It’s also clear that the drug war has disproportionately affected minorities.

“In every year from 1980 to 2007, blacks were arrested nationwide on drug charges at rates relative to population that were 2.8 to 5.5 times higher than white arrest rates,” according to the Human Rights Watch.

In fact, the Brookings Institute now estimates that an African-American man without a high school diploma will face a 70 percent chance of imprisonment by his mid-thirties.

Latinos, too, seem to be disproportionately affected by the drug war. Hispanics make up 17 percent of the U.S. population, but 37 percent of people incarcerated in federal prisons for drug offenses, according to the Drug Policy Alliance.

"People of color experience discrimination at every stage of the judicial system and are more likely to be stopped, searched, arrested, convicted, harshly sentenced and saddled with a lifelong criminal record," notes the Drug Policy Alliance in a June 2015 report. "This is particularly the case for drug law violations."

To Die in Prison -- For Pot?

But the most extreme example of harsh drug sentences are the men serving life terms for marijuana offenses.

In 2010, Beth Curtis launched a website, LifeForPot.com, to create a database of nonviolent marijuana offenders who received life sentences. She says that there are no official statistics on these types of inmates, so she relied heavily on her own research and crowdsourcing from attorneys around the country.

Curtis has since vetted more than 100 inmates and features more than a dozen on the site.

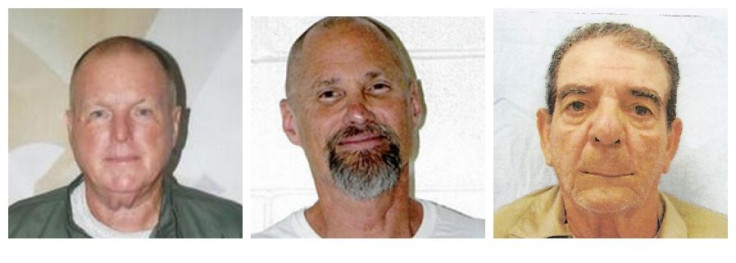

Those inmates include Fred Cundiff, a 68-year-old man who has been locked up for nearly 25 years. In 1991, Cundiff, who was married with three children at the time, drove to Tallahassee, Florida, to buy some weed. It ended being a sting operation. Because he had two prior convictions for growing pot, Cundiff was sentenced to life without parole.

“He now is in pain, immobile, without funds for basic necessities, and dependent on the kindness of strangers,” Curtis notes on her site.

There is also Paul Free, a former theater manager, serving a life term for selling pot -- a crime he has long claimed he didn’t even commit. Free is now 64 years old and 21 years into his sentence. And then there is Leopoldo Hernandez-Miranda, a Cuban immigrant, who claims he was making $50 per day as a day laborer when his boss put him in charge of guarding a safe house that contained some 3,100 pounds of pot. Days later, the safe house was raided by federal agents, and Hernandez-Miranda was arrested.

Working with two attorneys, Michael Kennedy and David Holland, Curtis has submitted a “Group Petition for Clemency” to Obama. She hopes that the website will bring attention to the men featured on the site. Though she has chosen to feature only marijuana offenders serving life sentences, she recognizes that many men and women are serving lengthy sentences for other types of nonviolent drug-related crimes.

“It's a fiscal problem, and it's an image problem” for the United States, Curtis says. “It comes down to whether or not we value our freedom.”

She adds, “But with marijuana being legalized [in some states], that's just pretty egregious.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.