The Threat Of A Declining China

Opinion

Many Americans view China’s emergence as the world’s second largest economy with trepidation. The United States, it seems, is in decline. China is a “rising power” destined to take over America’s role as global hegemon sometime in the not-too-distant future.

Recently, however, China’s prospects are looking less rosy. First quarter GDP grew only 7.7 percent, down from an already subpar 7.9 percent in the fourth quarter of 2012. Exports are slowing and the investment-led growth upon which the country has relied in the past is clearly unsustainable. Beijing is hoping to keep the economy on track by transitioning to a new “growth model” based on consumption and productivity gains. Yet so far there is little evidence to suggest that this strategy is working. Indeed, there is really no reason to believe that such a transition can be achieved under the country’s current political-economic system.

As the Chinese juggernaut starts to lose momentum, should Americans be breathing a collective sigh of relief? Not really. Unfortunately, China’s decline is likely to be a lot less peaceful than its rise.

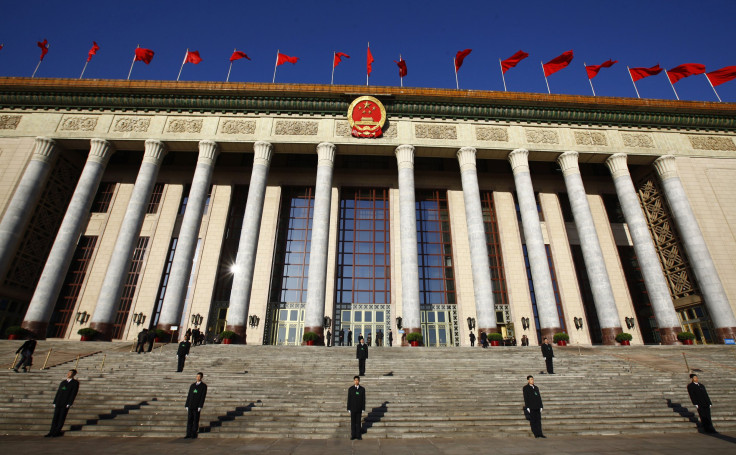

Slower growth will pose an existential problem for the Chinese Communist Party. Ever since the end of the Maoist era in 1978, economic development has been the Party’s primary source of legitimacy. A prolonged slowdown will weaken its hold on power in much the same way that crop failures during imperial times undermined the emperor’s claim to the “mandate of heaven.” If China is not going to be “number one” after all, some other justification for Party rule will be urgently needed.

The Party’s best bet will be to play the nationalist card, making the defense of the “motherland” its primary mission. This will not be difficult. It will be easy to blame China’s economic failures on the machinations of foreign powers, even as Mao Zedong did in his famous speech proclaiming the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949. The fact that China had “fallen behind,” he said, was “due entirely to oppression and exploitation by foreign imperialism and domestic reactionary governments.”

It will also be easy to put the Chinese economy on a war footing. China’s central planning institutions are well suited to the mobilization of resources for defense industries. A military buildup would also help to alleviate excess capacity problems in heavy industry. Total excess capacity in the steel sector, for example, already exceeds total U.S. capacity. Arms manufacturing is likely to be seen as a good way to put idle plants back online.

The implications for China’s neighbors are already evident in Beijing’s increasingly bellicose insistence on irredentist territorial claims. There have been escalating tensions with Japan over the Senkaku Islands, spats in the South China Sea involving areas claimed by Vietnam, and even a Chinese incursion into an Indian-controlled Himalayan region claimed by both Beijing and New Delhi.

Such incidents are often described as competitions for the control of natural resources such as the South China Sea’s oil and natural gas. They are, however, better understood as consequences of the Party’s domestic agenda. And as public relations exercises they have been remarkably successful. Chinese anti-Japanese sentiment is now at fever pitch, with many of China’s netizens expressing strident support for military action against Japan to recover lost territories, right historical wrongs, and avenge past humiliations.

U.S. policymakers need to realize that this type of nationalist sentiment is going to be the Party’s ace in the hole once the economy slows. Beijing can therefore be expected to prefer that international disputes remain unresolved. Its objective will be to keep the Chinese public distracted by possible foreign threats to China’s national security and economic development.

China, not the U.S., is fated to be the “declining power” for the remainder of this decade. This means that Washington’s preferred policy of ‘engagement’ will not work. Beijing will be unable to give ground in disputes with its neighbors because doing so will weaken the Party domestically. Events like the recent summit between President Obama and General Secretary Xi Jinping are not going to improve U.S.-China relations when the Party’s survival depends on escalating tensions.

Given that dialogue is likely to be ineffective, the U.S. must focus instead on defending its strategic interests in the Pacific. It must continue to strengthen ties with its regional partners, particularly Japan and Taiwan, which are likely to be the main targets of Chinese military adventurism. Most important, the U.S. must avoid helping the Party stifle demands for political reforms at home by handing it easy victories abroad.

Dr. Mark A. DeWeaver manages the emerging markets fund Quantrarian Asia Hedge and is the author of “Animal Spirits with Chinese Characteristics: Booms and Busts in the World’s Emerging Economic Giant.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.