Tiny Bacteria Produce And Release ‘Food Parcels’ Into Ocean For Marine Organisms: Study

Marine cyanobacteria, tiny ocean plants that produce oxygen and make organic carbon using sunlight and carbon dioxide, also help feed other marine organisms, according to a new study.

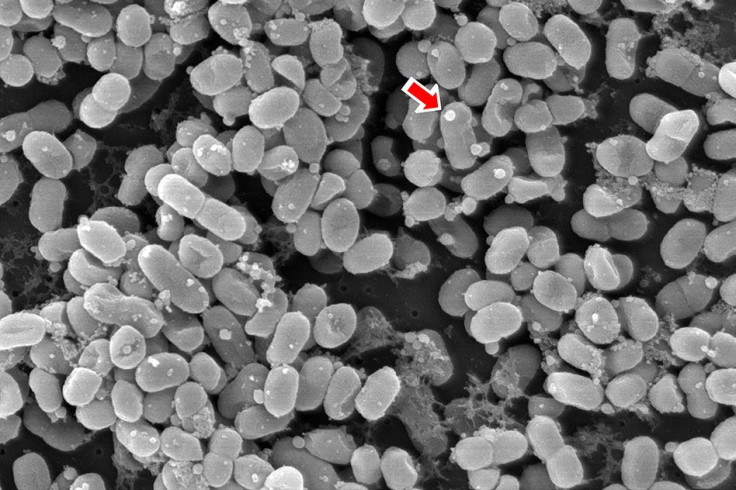

Cyanobacteria, which are thought to be one of the first single-celled organisms to inhabit the Earth, are said to nourish other organisms with oxygen and their own body mass. But according to researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, there is another dimension to the significant role played by these tiny cells in the ocean food chain: they continually produce and release vesicles, or round packages, containing carbon and other nutrients that serve as food for marine organisms.

“The finding that vesicles are so abundant in the oceans really expands the context in which we need to understand these structures,” MIT's Steven Biller, lead author of the study published in the journal Science, said in a recent statement. “Vesicles are a previously unrecognized and unexplored component of the dissolved organic carbon in marine ecosystems, and they could prove to be an important vehicle for genetic and biogeochemical exchange in the oceans.”

According to the study, the discovery of large numbers of extracellular vesicles -- lasting two weeks or more -- are associated with the two most abundant types of cyanobacteria: prochlorococcus and synechoccocus. The researchers compared the DNA sequence of the cyanobacteria cultured in their laboratory with the DNA of the vesicles (each about 100 nanometers in diameter) found in the ocean, and saw similarities between the two.

The scientists collected the vesicle samples from both the nutrient-rich coastal waters of New England and the nutrient-sparse waters of the Sargasso Sea, a region in the North Atlantic Ocean. Extracellular vesicles were first discovered in 1967 and have been studied in human-related bacteria, but this is the first evidence of their existence in the ocean.

The study of the vesicles taken from the seawater also revealed DNA from a diverse array of bacteria, suggesting that vesicle production is common to many marine microbes. The researchers estimate the global production of vesicles by prochlorococcus alone at many billions per day.

“Given the dearth of nutrients in the open ocean, the daily release by an organism of a packet one-sixth the size of its own body is puzzling, Sallie Chisholm, an MIT scientist who was part of the study, said in the statement. “Prochlorococcus has lost the ability to neutralize certain chemicals and depends on nonphotosynthetic bacteria to break down chemicals that would otherwise act as toxins. It’s possible the vesicle ‘snack packets’ help make this relationship mutually beneficial.”

According to the researchers, because the vesicles contain DNA, they likely facilitate the exchange of genes between individual bacteria, a process that is known as horizontal gene transfer. In addition, researchers said, the vesicles could even help defend against viruses. When viruses, or phages, that are known to attack cyanobacteria are mixed with the vesicle, it renders the viruses inactive, a process that makes the scientists speculate that the vesicles function as cellular decoys for deflecting viruses.

“By releasing extracellular vesicles these organisms shed new light on the importance of such particles in the largest ecosystem on Earth — the open ocean — with implications for marine carbon cycling, mechanisms of horizontal gene transfer, and as a defense against phage attack,” David Scanlan, a professor at the University of Warwick, who was not involved in this research, said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.