At Top Confederate General's Home Near Washington, Enslaved Voices Elevated

Statues of Robert E. Lee have been toppled as the United States grapples with its racist past but on a hill overlooking the nation's capital, the top Confederate general's house has been totally revamped.

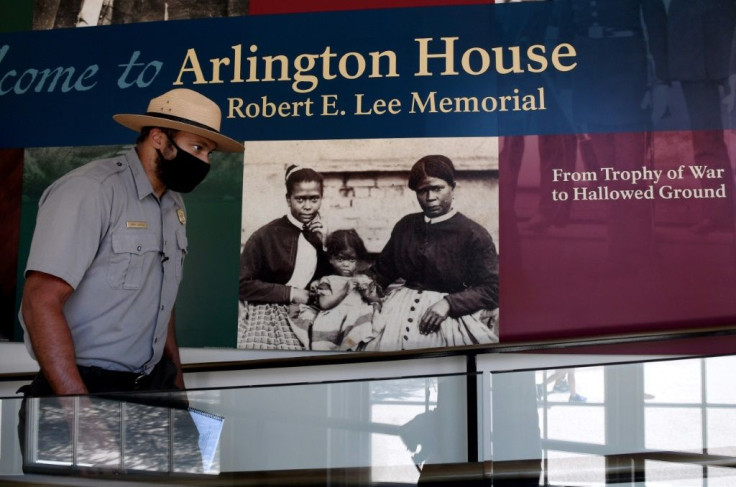

As Washington embarked on its usual humid, sweaty summer, "Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial," as the home is officially called, began welcoming visitors once again in early June after three years and more than $12 million in renovations.

The house's most impactful changes, however, were not just matters of brick and mortar: The home reopened with an aim of providing a more inclusive historical interpretation, its caretakers say.

Lee is a highly controversial figure: As the best-known Confederate general during the Civil War from 1861 to 1865, he helped lead the secessionist Southern states against the Union, in particular to preserve slavery.

Walking across the estate in late August, Aaron LaRocca, a ranger with the National Park Service, said that telling "a more holistic and inclusive story," by elevating the voices of those enslaved here, was a major point.

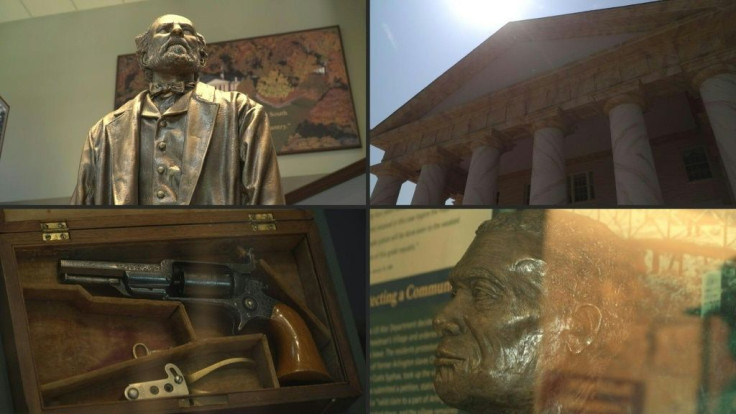

Unlike stone-cold statues, the mansion and its grounds -- which are part of the National Park Service and located inside Arlington National Cemetery -- reflect the real lives of actual people.

Telling the story of the more than 100 enslaved residents meant not only better incorporating their stories inside the mansion, but also creating new exhibits that fill two large buildings that were slave quarters. It also meant featuring particular individuals' histories.

Steve Hammond is a descendant of one of the enslaved families and has been volunteering at the house for approximately eight years, helping to tell the story of the residents "who many people are not familiar with."

Understanding Arlington House not only means tangling with the complicated history of Lee, but dipping a toe in the entire American saga.

At the base of the hill where the house sits is the late president John F. Kennedy's grave. The iconic Tomb of the Unknown Soldier is also nearby, as are hundreds of thousands of buried veterans.

The house itself was first built by George Washington's adopted grandson, George Washington Parke Custis, as an homage to the former president. His daughter, Mary Anna Custis, married Lee.

However, it is through Parke Custis' enslaved daughter, Maria Carter, whom he fathered with an enslaved woman, that Hammond is connected to Arlington House. He is a descendant of her husband's family.

Today, the descendants of those who lived at the house -- both the enslaved and the Lees -- meet routinely.

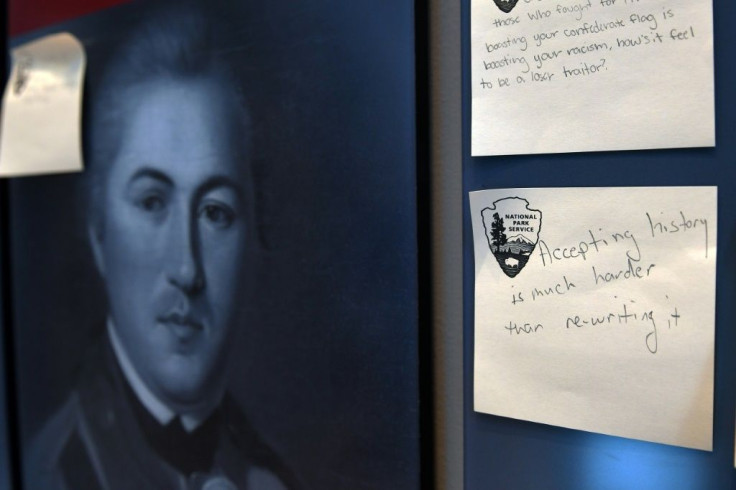

For many involved in expanding the site's narrative, a major sticking point remains Arlington House's official status as "The Robert E. Lee Memorial."

"The fact that we recognize it as a memorial to Robert E. Lee seems really out of date, especially in terms of where we are as a country today," said Hammond, 65, who is also a trustee for the Arlington House Foundation.

US congressman Don Beyer, whose district includes Arlington House, says he plans to reintroduce legislation nixing the house's Lee memorial status this session after a previous failed attempt, while philanthropist David Rubenstein, who funded the renovations, has urged the redesignation.

During the Civil War, the Union buried soldiers on Lee's property no doubt to deter his return, giving rise to Arlington National Cemetery, where more than 400,000 veterans and their dependents are buried today.

Congress officially recognized the site as a Lee memorial in 1955, citing his efforts after the war to reunify the country and authorized its current name in 1972.

"Memorials are a problem because a memorial is never about history, a memorial is about memory," said Denise Meringolo, a professor of history at University of Maryland, Baltimore County.

The idea of a joint educational museum and memorial is one that "complicates what we think we're supposed to be doing there."

Historically, Meringolo says, "it's been kind of white, middle-class people who've gone to historic houses and museums."

According to LaRocca, sites should be inclusive of diverse voices from the past in order to attract diverse visitors in the present.

Arlington National Cemetery welcomes more than three million guests a year and Arlington House over 600,000.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.