Trans-Pacific Partnership: TPP Will Make It Easier To Export US Natural Gas To Japan

The Trans-Pacific Partnership could boost exports of some U.S. energy supplies by making it easier to ship and sell the fuel to Pacific Rim nations. The biggest recipient likely would be Japan, which is eyeing deliveries of American liquefied natural gas to replace output from its nuclear power plants.

The 12-nation agreement completed in Atlanta this week is expected to call for the “national treatment for trade in natural gas,” a provision that would lower regulatory hurdles and cut tariffs among members of the free trade pact. If approved by Congress, the TPP likely would require the U.S. Department of Energy to approve automatically all gas exports to the 11 other nations, potentially accelerating LNG exports.

The DOE under current rules must decide whether it’s in the public interest to export LNG to nations that do not have free trade agreements with the U.S. So far, the agency has sanctioned five new export facilities to send LNG to such nations, including Japan and India.

Japan joined TPP negotiations in 2013 in large part because of its interest in cheaper U.S. gas supplies. The nation has phased out nearly all its nuclear power since the 2011 Fukushima meltdown and replaced the bulk of it with electricity from natural gas, which is significantly more expensive in the Pacific due to market inefficiencies and undeveloped pipeline capacity.

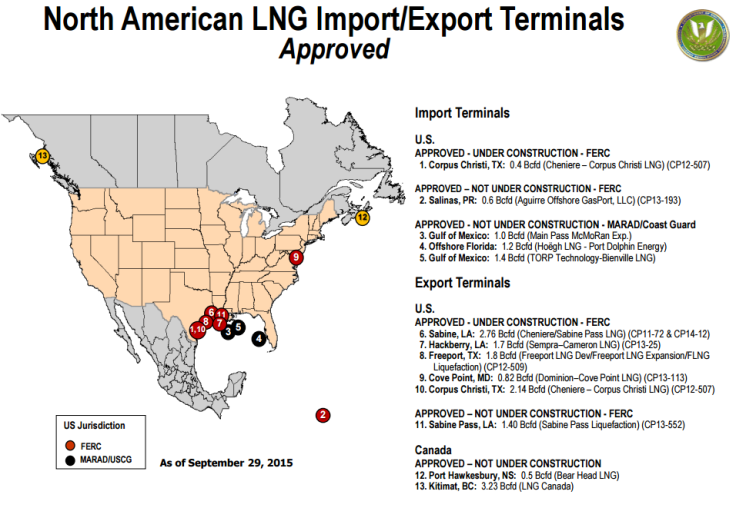

Liquefied natural gas is made by cooling natural gas until it becomes a clear, colorless liquid. In that form, fuel takes up less space than traditional natural gas and is therefore cheaper to transport and store. But exporting LNG requires building massive terminals on U.S. shorelines where supplies are loaded onto refrigerated tankers.

So far the U.S. has only one LNG export facility in operation: ConocoPhillips’ Kenai LNG Terminal near Anchorage, Alaska. Facilities in Louisiana, Maryland and Texas are under construction.

Environmental groups have long opposed expanding America’s LNG export capacity. They argue building new terminals will accelerate more natural gas drilling and fracking, boosting the threat of local groundwater contamination and increasing the world’s greenhouse gas emissions.

Sierra Club, Natural Resources Defense Council, 350.org and other major green groups this week blasted the TPP agreement, citing the uptick in natural gas consumption. The free-trade pact “would expand trade in dangerous fossil fuels that would increase fracking and imperil our climate,” Michael Brune, executive director of the Sierra Club, said in a statement.

But energy analysts said the TPP won’t likely drive a spike in LNG exports, at least not in the short term. The DOE already has approved the export of more than 10.5 billion cubic feet of natural gas a day, including to Japan and other non-free trade agreement countries. As a result, the TPP’s impact is “minimal,” Erica Bowman, chief economist for America’s Natural Gas Alliance, an industry advocacy group, told NPR’s StateImpact this week.

LNG exports could rise over time, however, if new export facilities no longer need the DOE’s trade approval to ship supplies to Japan and across the Pacific Rim, Bowman added.

The TPP is not expected to affect other U.S. energy exports, including coal and crude oil, experts said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.