Turkey Nixes Nuclear Power Plant Deal With Japan

KEY POINTS

- Turkey’s first nuclear plant, in Akkuyu, is slated to become operational in 2023

- Turkey has longed to have nuclear power since 1960s

- Erdogan is determined to lower Turkey’s dependence on energy imports

Turkey has canceled an agreement with a Japanese-led consortium to build a 4,500-megawatt nuclear plant in Sinop in northern Turkey along the Black Sea coast. The Sinop site would have been Turkey’s second nuclear plant

Turkish Energy Minister Fatih Donmez said that results of feasibility studies conducted by Japan’s Mitsubishi Heavy Industries did not meet the ministry’s expectations with respect to completion date and pricing.

The Japanese and Turkish governments originally agreed to the venture in 2013.

“We agreed with the Japanese side to not continue our cooperation regarding this matter,” Donmez said, adding that Ankara will now likely discuss construction of the proposed plant with other countries.

"Construction of the nuclear plant in Sinop with another partner is on the table," the minister said.

The Sinop project was already in trouble in 2018 when a financial crisis in Turkey led to a spike in financing costs. Ankara officials also raised questions about the plant’s rising safety costs and prospects for profitability.

Turkey and Russia’s state-owned nuclear energy firm Rosatom are already constructing the first Turkish nuclear plant, Akkuyu, in Buyukeceli, Mersin Province on the southern coast along the Mediterranean. Moscow and Ankara signed an agreement to build the plant back in May 2010.

Upon completion, Akkuyu is projected to generate about 35 billion kilowatt-hours of electricity per year and have a service life of 60 years. The first reactor of the Akkuyu plant is expected to be operational in 2023 – on the 100th anniversary of the founding of the modern Turkish state/

The Akkuyu plant is reportedly the largest joint project between Russia and Turkey and its $20 billion price tag is fully funded by Moscow. As a result, Russian companies will have a 51% ownership stake in the facility.

The Akkuyu plant will have four reactors and is anticipated to provide about 10% of Turkey’s total electricity needs.

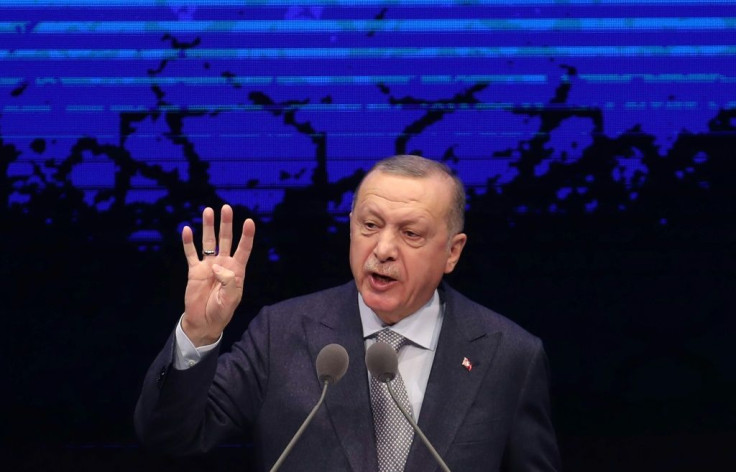

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan remains committed to a nuclear future for his country as a means of accelerating economic growth and lowering dependence on energy imports.

Turkey currently imports 98% of its natural gas and 93% of its oil.

Mehmet Ogutcu, a former diplomat and now chair of the London Energy Club and the Bosphorus Energy Club, said Turkey has dreamed of developing nuclear energy since the 1960s – but all ventures led nowhere until the Rosatom project at Akkuyu.

Ogutcu suspects, however, that previous failures might have been caused by some western powers’ perception that Turkey’s real agenda in securing nuclear power was to develop nuclear weapons.

“Hence, the conspiracy theorists believe that there has always been a ‘hidden hand’ determined to keep Turkey from nuclear energy technology,” Ogutcu wrote. “The link between nuclear weapons and civil nuclear power is often denied by the [Turkish] nuclear energy industry.”

Ogutcu further said that the Turks may seek to construct yet another nuclear plant in Igneada in Kirklareli province on the Black Sea, near the Bulgarian border.

But given the Chernobyl disaster in nearby Ukraine in 1986, not everyone in Turkey is eager to go nuclear.

“It is not easy to convince people completely of the benefits of a nuclear plant within the borders,” Ogutcu wrote. “In the public debate, there is no shortage of prejudice, misperception and ideological preferences for a variety of reasons, including public opposition, high capital cost and financing difficulties, and insufficient governance and management capacity on the part of the Turkish state agencies.”

The biggest concern of all, he added, is the lack of an independent nuclear regulator and a ‘‘safety culture’’ in state institutions “that is commensurate with the risks inherent in nuclear operations. Public consultation and dispute settlement mechanisms does not exist yet. Political concerns and bureaucratic interests might be at play instead of technical assessments of supply and demand.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.