UN Climate Change Report: World Must Phase Out Most Fossil Fuels To Avoid Catastrophic Global Warming

The world must stop using nearly all electricity from coal, oil and natural gas by 2100 to avoid the most damaging effects of climate change, such as surging sea levels and widespread food shortages, according to a United Nations report released this week. But heeding the U.N.'s advice also means huge employment changes: Thousands of jobs in the fossil fuel sector would be lost as new positions in the "green" economy are created.

Such a dramatic switch would help reduce the levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere and, in turn, keep the planet from warming to a catastrophic degree, the U.N.-led Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change said in its latest status report. The panel reiterated its targets of getting 80 percent of electricity from renewable and low-carbon sources by 2050, and 90 percent by the century's end.

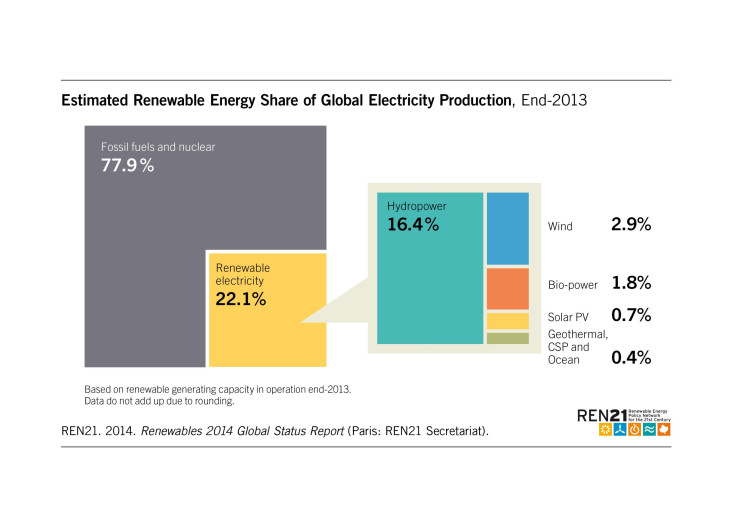

To meet those goals, countries would have to flip the global electricity system on its head. Fossil fuels today make up roughly 70 percent of total electricity production. The remaining 30 percent comes from nuclear power plants, which do not emit greenhouse gases, and renewables, including wind, solar, geothermal, hydropower and biomass.

All told, power plants account for about one-third of the world's emissions.

On a technical basis, the ability to swap coal and gas-fired plants with renewables isn't as far-fetched as it seems, according to scientists and analysts who study the low-carbon future. Many of the necessary clean-energy technologies already exist in the field or lab. An analysis of the U.S. grid found that renewables could provide most of America's power by 2050 if certain investments and improvements to infrastructure are made, the U.S. Department of Energy-run National Renewable Energy Laboratory concluded.

"There's a consensus in the research community that 80 percent renewables is possible," said Trieu Mai, a senior energy analyst at the lab in Golden, Colorado. "The technical engineering knowledge has pointed in that direction."

Yet enormous financial and political obstacles remain in the way.

Countries will have to spend an additional $1 trillion a year over the next four decades to meet the 80-percent target, for a total of $44 trillion, the International Energy Agency has estimated. Last year's clean-energy investment, by comparison, totaled just $254 billion globally.

Some of that money will help to install the solar panels and wind turbines we use today. But much of it will be plowed into the research, development and deployment of fledgling technologies that are not yet mature or cheap enough to replace fossil fuel electricity. Those include advanced battery systems that store up excess wind and solar power, and then feed it back into the grid when the wind isn't blowing or the sun isn't shining. Engineering tools that allow grid operators to manage and balance less-predictable electricity supplies are also still being scaled up. And highly energy-efficient appliances, controls and materials for buildings, which help reduce demand for electricity, are still too costly to be widely used.

To spur these investments and installations, governments will have to adopt far more aggressive policies than the measures in place today, putting leaders at odds with the lucrative fossil fuel industry. According to the U.N. panel, the most effective way to achieve the clean-energy targets is to put a global price on carbon dioxide emissions, which would penalize companies that burn and extract fossil fuels and make renewables more attractive as a result.

While momentum is building globally for such a strategy, growing opposition in the United States and India -- the world's second- and third-largest polluters, respectively -- threatens to undermine progress. At a major U.N. climate summit in New York City last September, both countries declined to sign a declaration that called for a price on carbon. More than 70 countries -- including China, the biggest polluter -- joined the nonbinding pledge, along with 1,000 companies and investors.

Prakash Javadekar, India's new environment minister, said his country shouldn't be forced to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions when 20 percent of its people don't have access to electricity. "India's first task is eradication of poverty," he told the New York Times at the time. "We will grow faster, and our emissions will rise."

In the United States, conservative lawmakers staunchly oppose existing and future policies that seek to limit the role of fossil fuels in America's energy mix. In nearly half the country, politicians have tried four-dozen times to eliminate or weaken state mandates for clean energy. In June, Ohio became the first state to pass such a measure when Republican Gov. John Kasich agreed to "freeze" the state's Renewable Portfolio Standard and energy efficiency goals.

More than a dozen coal-reliant states are suing the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency over its Clean Power Plan. The policy, approved in June, would require states to cut carbon output to 30 percent below 2005 levels by 2030 and is a signature piece of President Barack Obama's Climate Action Plan.

Opponents of these and other climate measures say the policies would ramp up electricity costs -- making it harder for businesses to operate -- all while eliminating thousands of jobs in the fossil fuel industry. The same goes for a global price on carbon. "You're going to see the electricity and energy systems change for the worst," said Chris Warren, a spokesman for the Washington, D.C.-based Institute for Energy Research, which analyzes U.S. oil, gas, coal and electricity markets.

He said the U.N. panel's targets for reducing fossil fuels are "unattainable and not realistic," given the scale of the challenge, and would impose "astronomical costs" on not only the U.S. but also developing economies like China and India.

Supporters of a clean-energy transition argue that the costs of transforming the electricity system will pale in comparison to the price society will pay in a warmer world. Climate scientists project that extreme weather events will become more frequent and intense as global temperatures rise. Severe droughts, dangerous heat waves, torrential downpours and sweeping wildfires will also become more common -- racking up trillions of dollars in damage and economic losses.

"The sooner we act, the less costly it will be," said Doug Vine, a senior energy fellow at the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, an environmental advocacy group in Washington.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.