US-China Climate Change Deal: Presidents Obama And Xi To Discuss Emissions Goals At White House

U.S. President Barack Obama and Chinese President Xi Jinping will make climate change a top focus during meetings in Washington this week. The leaders are expected to build on last fall's historic joint agreement to curb U.S. and Chinese carbon emissions and boost development of cleaner energy supplies.

Xi arrived in Seattle Tuesday for his first state visit. The Chinese president is slated to meet with Obama Thursday night and Friday at the White House, where the two will discuss climate issues, cybersecurity, China’s military ambitions in Asia and the country's recent economic troubles.

Obama and Xi last discussed climate issues in November during Obama's trip to Beijing. After months of negotiations, the two administrations announced joint commitments to curb their countries’ carbon footprints. Obama pledged to cut America’s emissions by up to 28 percent below 2005 levels by 2025. Xi proposed to cap China’s rapidly rising emissions within the next 15 years -- the first time China agreed to halt its growth in carbon pollution.

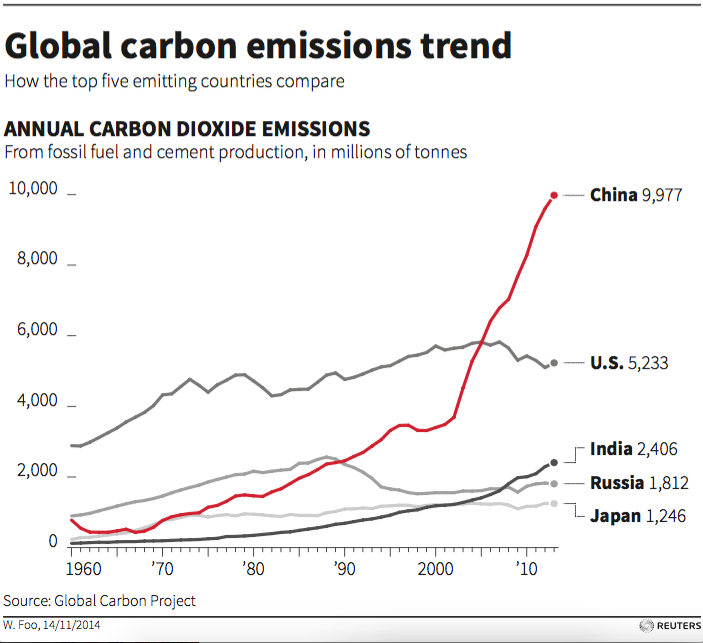

China is now the world's top emitter of carbon dioxide, a title it wrested from the United States in 2006 as the Chinese economy soared and energy consumption exploded. China accounted for more than a quarter of the world’s total greenhouse gas emissions in 2012, primarily by burning coal, oil and natural gas to power factories and vehicles. (Recent studies, however, suggest huge uncertainties in data from China on its carbon emissions). The United States is the second largest emitter, contributing to over 14 percent of total globa emissions in 2012.

For years, both China and the U.S. resisted international pressure to set limits on their emissions, arguing that such a move could jeopardize economic growth. The Obama administration proved reluctant to establish aggressive reductions unless major competing economies like China followed suit. Chinese leaders, meanwhile, argued that the richest nations -- which have historically spewed the most carbon -- should commit to stricter standards.

Obama and Xi's joint committment in November broke that logjam, and now both countries have said they will work together to meet their climate targets.

“Last year was about the U.S. and China making those commitments,” Brian Deese, Obama's senior adviser on climate change, told the New York Times last week in Los Angeles. U.S. and Chinese negotiators met in California to announce joint actions by dozens of cities, states and provinces to curb emissions. A handful of Chinese cities pledged to halt their emissions growth by 2020, ten years before the national target.

“This year, having made those commitments, needs to be a year of implementation, as our two countries demonstrate commitment to implement those goals with concrete steps," Deese told the Times.

Critics have argued both U.S. and Chinese emissions goals are too weak to address the mounting threat of climate change, which is causing sea level rise, brutal droughts and more violent storms. Still, the U.S.-China partnership has breathed new life into global climate change negotiations and inspired emissions cuts in other countries. Nearly 200 nations have agreed to forge a committment to reduce their individual emissions at a United Nations conference in Paris this December. The Obama and Xi administrations said they are now pushing to solidify such a deal.

The U.S. is expected to reach its 28-percent emissions target through existing state policies and federal laws, including the Obama administration's Clean Power Plan to cut carbon from coal-fired power plants, the World Resources Institute found in a May analysis. But reversing the rise in China's emissions growth will require a massive overhaul of the country's energy sector, according to experts on Chinese energy policy.

Fossil fuels accounted for more than 90 percent of China's total energy consumption in 2012, including 66 percent from coal alone, the U.S. Energy Information Administration estimated. (In the United States, by comparison, fossil fuels supplied about 80 percent of total energy consumption that year, though renewable energy supplies in both countries are quickly growing.) China has pledged to diversify its energy mix and double its share of non-fossil fuel consumption to 20 percent -- a feat that will require building more solar, wind, nuclear and biomass power than the U.S. has installed today.

Still, the policy experts said they feel optimistic that China can meet its goal to stop emissions from growing by 2030.

“There’s a much greater degree of political will in China than I’ve ever seen” on climate issues, said Kelly Sims Gallagher, a former senior policy adviser in the White House’s Office of Science and Technology Policy. Much of that push comes in response to the chronic air pollution choking China’s largest cities, which is raising pressure on China’s leaders to shut down coal-fired power plants and invest in cleaner energy supplies.

Xi is also responding to calls from global leaders to become a “responsible stakeholder” in international issues, Gallagher said at a Monday panel on China hosted by Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy in New York. “Cooperation on climate helps to embody Xi Jinping’s proposal for a new model on relations,” she added. “In some areas, China is trying now … to shoulder the responsibility for global issues.”

Zhu Liu, a postdoctoral research fellow at Harvard University, said China will have a better shot at meeting its 2030 target if its economy continues to slow, dampening the demand for high-carbon coal in energy intensive industries.

China's coal consumption fell in 2014 for the first time in a century due to a mix of environmental restrictions and sluggish manufacturing, according to statistics from the China National Coal Association. China's economic growth is projected to dip to 6.7 percent in 2016, down from a projected 6.8 percent this year and 7.4 percent in 2014, according to the Organization for Economic Development and Cooperation.

But Liu cautioned that a drop in China's emissions from lost manufacturing activity could translate into higher emissions elsewhere if another country picks up the slack without adopting cleaner energy. "The peak [emissions] issue is not just China's issue," he said Monday at the Columbia panel. "To protect our environment, we need to consider our whole footprint."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.