In US, An Effort To Commemorate Thousands Of Lynching Victims

More than 120 years ago, a Black man was accused of raping a white woman in the city of Decatur, Illinois, but before Samuel Bush could be tried, a vicious mob forcibly took him from a local jail, beat him and hung him from a telephone pole. Now, an effort is underway to memorialize the brutal lynching.

"We learn from past mistakes so it doesn't happen again," said Rich Hansen, a local high school history teacher who is campaigning to dedicate a memorial to Bush in the American Midwestern city. "If we as a nation are going to move past this racial divide, we need to first of all be educated in what came forth and understand why it happened."

A year after the killing of George Floyd set off a nationwide wave of mass antiracism protests, activists are mounting a campaign to honor the memory of several thousand African Americans who were lynched throughout the country from the end of the US Civil War through the end of World War II.

But as the United States undergoes a broader national reckoning over racial justice, the effort is facing a backlash in some communities.

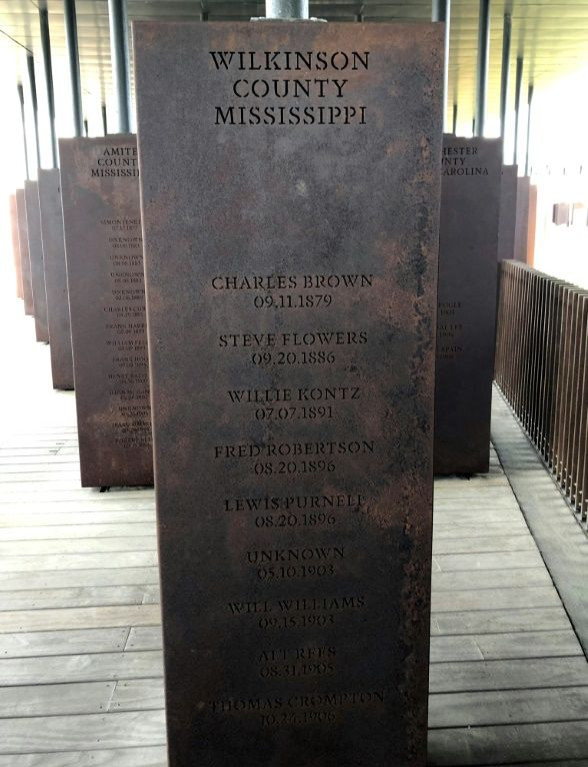

The Equal Justice Initiative, a racial justice advocacy group based in Montgomery, Alabama, has documented more than 4,400 victims of lynchings nationwide from 1877 through 1950. In 2018, it opened the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, where more than 800 weathered steel columns etched with the names of lynching victims hang from the ceiling.

The group also collaborates with local communities to gather soil at lynching sites to be displayed in glass jars with the victims' names, and to erect narrative markers in public locations throughout the country where lynchings took place.

"This was a horrible time in our past, but we need to look at it and we need to learn from it so it never happens again," said Melissa Thiel, a historian who is campaigning to erect a memorial commemorating another brutal lynching that took place in the city of Sherman, Texas.

In 1930, as America was going through the Great Depression, a Black day laborer named George Hughes was lynched after he was accused of assaulting the wife of his white boss as he tried to collect $6 in payment for his work. The lynching led to a rampage, in which Black businesses were burnt to the ground.

However, Thiel's efforts have met resistance in a city where a towering stone monument to the pro-slavery Confederacy stands next to the courthouse. Local officials have stonewalled Thiel's plans, saying they don't want to relive a past tragedy.

But Thiel is undeterred: "Do we talk about World War II? Do we talk about the Holocaust? Do we talk about 9/11? These histories are very difficult and tragic, but that's okay to talk about," she said.

Sometimes resistance to racial reckoning can take a more violent form, as was the case in Kansas City, Missouri, another former Confederate state.

In 2018, activists put up a plaque in memory of Levi Harrington, a Black man who was lynched in 1882 after being falsely accused of shooting a police officer. But at the height of the Black Lives Matters protests last year, someone vandalized the memorial, cutting it off at its base and tossing it off a cliff.

The plaque was later retrieved and placed outside the Black Archives of Mid-America in Kansas City, a museum of African-American history. ?

The Equal Justice Initiative is now working on creating a new memorial and plans to re-dedicate it in the coming months, according to Black Archives' executive director Carmaletta Williams.

"It's because of an innate fear that somehow the self-identity that they built as the power of the country is no longer the truth," Williams said. "It's been recognized all over that white men and white privilege does not give you a special place in this country anymore, so they fight."

But lynchings were not only confined to Confederate states. In Duluth, Minnesota, about as far north as one can go in the United States, the Clayton Jackson McGhie memorial is dedicated to three Black men lynched in 1920.

Avi Viswanathan, the director of inclusion and community engagement at the St. Paul-based Minnesota Historical Society, said the fact that the memorial is in a northern state that fought the Confederacy in the Civil War -- and also the state where Floyd, an unarmed Black man, was killed by a white police officer last year -- is a reminder of the constant work that needs to be done.

"We don't want to isolate ourselves from the stories of the past because they can repeat. And as we saw with George Floyd, systematic racism and violence against (Black people) is still present," Viswanathan said. "So, if we force the stories of the past, we cannot see the context now and we will not be in a position to prevent it from happening in the future."

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.