US Federal Reserve Keeps October Rate Hike On The Table, But The Odds Are Slim

The ongoing speculation over whether the Federal Reserve will raise benchmark interest rates in October is exposing the tension between critics of accommodative monetary policy and data hard-liners with their eyes on inflation.

As Fed officials tell it, an interest rate hike is still in the offing when the Federal Open Markets Committee meets Oct. 28. In a speech last week, Fed Chair Janet Yellen said that she expected the central bank to move by the end of 2015, leaving just October and December meetings available for action.

Meanwhile, St. Louis Federal Reserve President James Bullard said the possibility is open, but cast doubt on an October rate hike. In comments Monday, William Dudley of the New York Fed encapsulated the contradictory viewpoints, repeating his colleagues’ convictions that rates should come up in 2015, while emphasizing that the decision should hinge on the data.

Taking a more dovish tack, Chicago Fed President Charles Evans diverged with his colleagues Monday in suggesting that they wait until 2016 to raise historically low interest rates. In comments prepared Monday for an appearance at Marquette University, Evans advocated an "extra patient approach" to a rate liftoff.

Financial markets agree. Futures used to hedge interest rate increases currently imply a slim 11.5 percent chance that the Fed will act in October.

And analysts are equally unconvinced that October will see the first hike in benchmark interest rates in nine years. After the Fed’s decision earlier this month to keep rates suspended near zero, the economic team at Goldman Sachs kept its sights on December, while analysts at Citigroup and Pimco have pegged a hike for early 2016. “They’re under very little pressure to actually do anything,” says Steven Ricchiuto, chief economist of Mizuho Securities, who has predicted an early 2016 rate hike for several years.

Why the uncertainty? The Fed has a dual mandate of keeping inflation in check while maximizing employment. Low interest rates can help spur investment and create jobs, though they run the risk of leading to inflation if kept low too long.

Since the Fed dropped interest rates to historic lows seven years ago, jobs have come back; the headline unemployment rate stands at just over 5 percent. But inflation growth has proven elusive, with core inflation measures stuck stubbornly below the Fed’s 2 percent target.

Recent economic indicators have flashed positive. Newly revised second-quarter GDP growth came in at a brisk 3.9 percent, and consumer spending ticked up in August. But Ricchiuto says as far as a pickup in inflation is concerned, “there’s no evidence that it’s happening.”

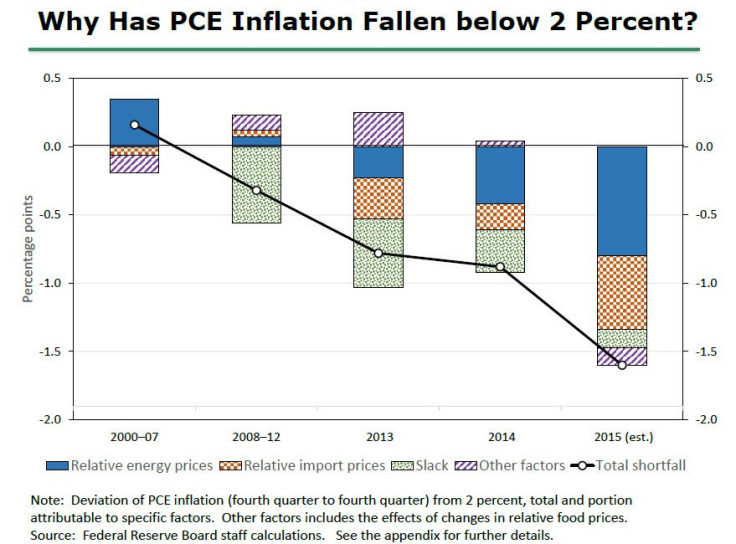

In comments after the Committee meeting that kept interest rates near zero, Yellen said that “transitory” pressures were keeping inflation down -- by the Fed’s models, roughly 80 percent of the shortfall in expected inflation can be explained by the recent strengthening of the dollar and low energy prices.

But if those trends prove more durable than the Fed thought, a jump in inflation could remain a distant possibility, indicating in part that the economy has more room to grow. Yellen has pondered the possibility that headline unemployment measures mask vast reserves of slack in the labor market that keep inflation from heating up.

Still, some market participants counter that the Fed should raise rates even with inflation below target. Billionaire investor Carl Icahn has sounded the oft-heard warning that near-zero interest rates have inflated a dangerous asset bubble. Others, like economists at the bank HSBC, have cautioned that keeping interest rates at an absolute minimum leaves central banks without ammunition should recession hit.

A few Fed officials have echoed those concerns, though they remain a minority voice in the rate-setting committee.

The coming week will provide plenty more Fed prognostications to parse. Yellen and Bullard will speak Wednesday at the Third Annual Community Banking Research and Policy Conference. San Francisco Fed President John Williams speaks in Utah Thursday. And a conference Friday will hear remarks from Boston Fed President Eric Rosengren, Minneapolis Fed President Narayana Kocherlakota and Cleveland Fed president Loretta Mester.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.