US Federal Reserve’s ‘Dot Plot’ Of Interest Rates Appears Increasingly Out Of Touch

The U.S. Federal Reserve’s so-called dot plot of the path of interest rates has become increasingly detached from financial markets’ rate projections and risks sending an overly hawkish message that may undermine the central bank’s credibility. Despite falling inflation expectations and turmoil in financial markets this week as concerns about growth mounted, the Fed hewed to its message that it could build on December’s rate rise with further hikes in 2016.

Quite how many rises is unclear, and there is just one tool economists can use to get an idea: a chart in the Fed’s quarterly “Summary of Economic Projections” known colloquially as the dot plot. The chart shows individual Fed rate setters’ expectations, although they are not identified by name.

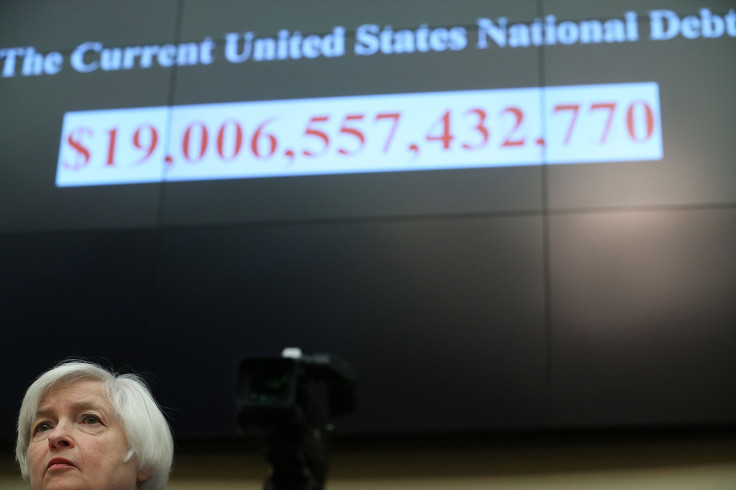

Both Fed Chair Janet L. Yellen and Federal Reserve Bank of New York President William C. Dudley suggested this week that rate rises were still on the cards, pointing to the underlying health of the U.S. economy. Neither referred directly to the dot plot that envisages four rate hikes this year, versus market pricing of a one-in-three chance of even a single rate rise this year. Fed officials say that while the dots, issued every quarter, do not represent a rate path per se, they can be used to manage expectations.

“Part of the problem is that it is consistently wrong,” said Tim Duy, an economics professor at the University of Oregon. “The second part of the problem is that the Fed doesn’t seem to recognize how terrible their forecasts have been.”

Fed officials have had to regularly ratchet down their dot-plot forecasts since they began publishing them four years ago. At the time the Fed said the publication of individual rate forecasts would give markets a better idea of where the Fed was heading. Economists say it was a useful signaling tool to reinforce the bank’s commitment to zero rates.

“I think they have outlived their usefulness and they risk sending a signal that [Fed officials] have a ‘plan’ rather than that they are data dependent,” said JPMorgan Chase & Co. economist Michael Feroli.

Before Yellen’s appearances at congressional hearings last week, she had not spoken since signing off on the December rate rise. And she has no listed speaking engagements until the March Federal Open Markets Committee meeting, a gathering the Fed had wanted to keep on the cards for a potential rate rise.

The Federal Reserve appears to have no plan to ditch the dots. Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco John C. Williams suggested last month that they remain a central part of the Fed’s policy toolbox, telling reporters they are a means for policymakers to “adjust the path of policy down” if the economy takes a turn for the worse.

The problem with the anonymous dot plot is that it does not provide a clear picture of the Fed’s majority view. Because the forecasts are anonymous, critics say, economists end up guessing which dot belongs to Yellen.

The International Monetary Fund is among the critics of the current arrangement. Much better, it and others believe, would be to issue a staff forecast, similar to what the European Central Bank produces, so that analysts and the public have a clearer view of where the Fed thinks the economy and rates are heading. Members of Congress have made similar suggestions.

But the idea has always foundered at an institution whose various members give different weight to different bits of data, have different views on policy, and have a plethora of staff forecasts and models volleying around the Washington-based board of governors and 12 regional banks.

Yellen herself has run both hot and cold on the dot plot. In March 2014, she warned against giving the rate forecasts too much weight. A year later, she elevated their importance by listing the median dot reading along with the rest of the Fed’s projections on growth, unemployment and inflation, and providing new color about the thinking behind some of the dots.

Many economists expect the Fed to lower its dot-plot forecasts yet again when it publishes new ones after its next policy-setting meeting in mid-March. “The median of the dot plot will likely migrate to three rate hikes or maybe even two quarter-point rate hikes for 2016,” predicted Bank of the West economist Scott Anderson.

Even that puts the Fed far from what many investors expect.

As much as the Fed would like to think its dot plot manages market expectations, it is likely to have to bring it in line with the market’s interest-rate outlook, said economist Diane Swonk. “They have been unwilling to capitulate, and they’ve really wanted to separate themselves as not being beholden to Wall Street,” said Swonk, founder of Diane Swonk LLC in Chicago. “But at the end of the day, they are.”

© Copyright Thomson Reuters 2024. All rights reserved.