US Military Readiness In Question Amid Calls For Syria Invasion Against ISIS

The rise of the Islamic State group and terrorist attacks in Paris and San Bernardino, California, have prompted calls for the U.S. to engage in a new war in the Middle East. Republican presidential candidates Lindsey Graham, Marco Rubio, Jeb Bush and John Kasich say it’s time to send U.S. ground troops to Syria and Iraq.

President Barack Obama has deployed a small contingent of special forces to the region and requested congressional authorization in case he wants more. In a new CNN survey, a majority of Americans told pollsters they now support an invasion.

But while the American public may be ready for a new war, Pentagon officials have warned that the U.S. military may not be.

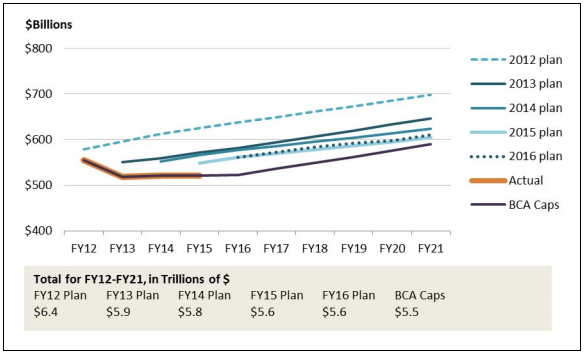

More than 14 years after the United States followed the 9/11 terrorist attacks with an invasion of Afghanistan and then Iraq, leaders of the armed forces and many military experts say America’s war-fighting machine is suffering a readiness crisis. In this “era of persistent conflict,” as military leaders call it, U.S. troop strength has been depleted by over-deployment and force reductions. Aircraft and ships are aging; bomb supplies are running out. The country’s military budget is 45 percent larger than it was before 9/11, but the military over the last decade has been asked to do far more. And recent budget cuts -- mandated by Congress -- have hurt the military’s ability to prepare for any new conflict, some experts say.

“We are unable to generate readiness for unknown contingencies and under our current budget, army readiness will at best flatline over the next three to four years," Army Chief of Staff Gen. Ray Odierno said earlier this year. Today’s military readiness is at “historically low levels,” he said.

Other combat branches of the armed services echo that message.

Gen. John Paxton, the assistant commandant of the Marines, told senators earlier this year that half of the corps’ units in the United States are not at “readiness levels needed to execute wartime missions, respond to unexpected crises and surge for major contingencies.” At the same Capitol Hill hearing, Admiral Michelle Howard said the Navy is “at our lowest surge capacity that we’ve been at in years.” And while presidential candidates of both parties have called for the United States to use its air power to enforce a no-fly zone over Syria, Air Force Vice Chief of Staff Gen. Larry Spencer said that when it comes to the “combat air forces that we have right now, less than 50 percent are fully spectrum ready.”

Last year, Military Times reported that most active-duty troops it polled said “readiness in their unit is either good, high or optimal.” But Todd Harrison of the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments told the newspaper that while soldiers can judge “near-term readiness,” they “can't see what readiness might be in five, 10 or 15 years from now when the equipment they are using today may no longer be serviceable.”

Aging hardware is indeed a top concern of Pentagon leaders. In 2010, the General Accountability Office reported that Navy officials found that fleet readiness had “declined over the previous ten years and was well below the levels necessary to support reliable, sustained operations at sea.” Military leaders told lawmakers in March that aircraft are now anywhere from 22 to 29 years old and F-18 jets are being flown for 60 percent more hours than the lifespan for which they were designed. Just last week, the Air Force -- which has been launching airstrikes on ISIS for 15 months -- warned of a possible shortage of bombs.

Mackenzie Eaglen, a defense analyst at the conservative American Enterprise Institute, told International Business Times that the degradation in military hardware and the attendant overall decline in readiness is primarily the result of two factors: long-term combat operations in Iraq and Afghanistan and sequestration -- the automatic, across-the-board spending cuts passed by Congress in 2013.

“There’s no doubt an intense, high-level, high pace of operations for 10 years and two theaters just wore the military plain out across the board,” Eaglen said. The budget cuts then “did so much damage to military readiness that all of the services will not recover from that one year’s consequences until at least 2020,” she said.

Military officials have long feared the effects of sequestration. Leon Panetta, then the defense secretary, warned in 2013 that the budget reductions would force the Pentagon to “cut back on Army training and maintenance” and “cut back on the ability to support the troops who are not in the war zone.” Sequestration also accelerated the federal government’s previous plans to reduce the size of the U.S. Army by 120,000 from where it stood when Obama first took office -- which will translate to a 21 percent reduction of active duty soldiers.

In its 2016 budget documents, the Army now says that if the cuts from sequestration are permitted to persist, they will end up “jeopardizing the Army’s ability to execute even one prolonged multiphase contingency operation” -- such as the one being proposed to fight ISIS in Syria and Iraq.

‘A Washington game’

Even at a time when high-profile lawmakers like Sens. Graham and John McCain are calling for an initial deployment of 10,000 troops into Syria and another 10,000 to Iraq, some experts dispute that the sequestration cuts have been severe enough to damage readiness. The U.S. military currently enjoys, by far, the largest budget of any defense force in the world.

The watchdog group National Priorities Project, for instance, has pointed out that Congress quietly restored many cuts, leaving the Pentagon’s 2013 budget less than 6 percent below pre-sequestration levels in 2013 and less than 1 percent below those levels in 2014. An analysis from the Washington-based Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) found that while the cuts would have an “important impact on U.S. deterrent and warfighting capabilities,” the Pentagon in fact had plans in place to prioritize readiness -- an assessment confirmed by some of the findings of a General Accountability Office review delivered to Congress this past spring.

That report found that following orders “to preserve military readiness and wartime operations,” military leaders ended up protecting funding for training the soldiers who were scheduled for imminent deployment. The GAO said at least one branch of the armed forces — the Marines — “avoided cancelling deployments or major exercises and reported no readiness effects as a result of sequestration.”

The brass are playing “a Washington game, where they say you want us to put 20,000 people into the Middle East so you have to increase our budget,” former Reagan Assistant Secretary of Defense Lawrence Korb told IBT. A military with a $500 billion annual budget and a standing army of more than 1.3 million personnel has plenty of resources for such a deployment and the term “readiness” is being misunderstood, Korb said.

“Readiness is a specific military term — they set standards for each unit and if you don’t meet those standards, you don’t get the readiness classification,” said Korb, who is now a senior fellow at the left-leaning Center for American Progress. “They are saying not all the units are where you would like them to be if you want to fight two wars, but what happens is that the common, ordinary person hears ‘readiness’ and they think it means more than the specific narrow definition that the military uses.”

Still, if a relatively small American deployment to fight ISIS grew into a large-scale conflict involving more than 100,000 troops, those concerns would become more acute and increase the chance of “mission failure,” said Eaglen of the conservative American Enterprise Institute.

But that's a real risk, Korb told IBT: Because presidents don’t want to be seen as “cutting and running,” small deployments can expand in pursuit of an outcome that can be labeled a victory. So-called “mission creep” would be especially problematic right now because units have been deployed more rapidly than normal.

“What’s happened is that we haven’t given the men and women in combat enough time between deployments,” he said. “Over the long haul, that creates serious problems.”

Korb authored a report showing that by 2007, more than 420,000 full-time troops had already been deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan more than once and another 84,000 National Reservists had been deployed multiple times. A Rand Corporation analysis found that since 2008, “the cumulative amount of time that a soldier has spent deployed has increased by an average of 28 percent.”

Multiple reports have suggested that such a deployment schedule can impair combat readiness.

- A report from the Army in 2006 found that soldiers ordered to serve multiple deployments in Iraq were 50 percent more likely to experience significant combat stress — and thus be at increased risk of post-traumatic stress disorder — than those who had served only one tour.

- A study sponsored by the New Jersey Department of Military and Veterans Affairs in 2010 found that repeated deployments “adversely affect the physical and mental functioning” and "adversely affect the military readiness" of the National Guard troops they studied.

- An analysis released by the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments last month reported that the accelerated schedule of Naval and Marine deployments risks “breaking the force” after a decade of “deferred maintenance, reduced readiness and demoralized crews.” That followed a report from the U.S. Naval Institute on how the pace of Marine Corps deployments has become “problematic for force health.”

‘Mythical Arab armies’

One proposal to alleviate war fatigue is an invasion plan that relies heavily on other countries to bear more of the burden of combat operations.

In a recent interview on CBS's "Face The Nation," Graham and McCain said their proposal for 10,000 American troops in Syria envisions the U.S. participants as only a small part of the at least 100,000 troops they say would be necessary to defeat ISIS.

“Let’s go on the offense,” Graham said. “Let’s get a regional army and go into Syria with American help — 90 percent the region, 10 percent U.S.- Western forces — and destroy the caliphate, take Raqqa away from [ISIS], destroy [ISIS] because this whole episode here is what happens when a terrorist organization is allowed to win and hold land.”

Such plans may have a large element of wishful thinking. It’s far from clear that potential U.S. allies have the political will or physical manpower to muster such a large fighting force. Graham himself has said, “These mythical Arab armies that my friends talk about that are going to protect us don't exist.”

In terms of Middle East and North African countries, Turkey’s Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu has said his government would consider sending ground troops across the border into Syria to fight ISIS, but he has not committed a set number and has suggested it would do so only as part of an international coalition. The United Arab Emirates has said it is willing to send ground troops to Syria — but its entire army has a total of just 44,000 troops and the country is already involved in the burgeoning war in Yemen. Saudi Arabia, Morocco, Egypt and Qatar have not committed to sending ground troops and their militaries are also already being deployed to Yemen.

As for European countries, U.S. Secretary of Defense Ash Carter expressed concern during a congressional hearing on Wednesday that America's NATO allies are not investing the resources necessary to defeat ISIS. NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg earlier this week said that sending ground forces is “not on the agenda of the coalition and the NATO allies.” French President François Hollande said last month, "France will not intervene militarily on the ground” in Syria. Germany’s government has approved a plan to send military forces to the Middle East — but only 1,200 military personnel and only in roles supporting other nations’ front-line troops. British Prime Minister David Cameron has not committed to sending ground troops, instead suggesting that continued allied airstrikes will embolden what he asserted are "70,000 Syrian opposition fighters on the ground who do not belong to extremist groups.”

The United States previously tried training some of what it called "moderate” rebels to combat ISIS in Syria, directing $500 million to a program to train over 5,000 rebels. But the Pentagon scrapped the effort in October after officials admitted that the military had trained just “four or five” Syrian fighters.

That leaves Russia as a key variable. In September, that country’s parliament approved the use of military force against ISIS in Syria, following Syrian President Bashar Assad’s request for airstrikes against Islamic State group targets. In October, Russian President Vladimir Putin drafted 150,000 people into the military, which already had 845,000 troops.

But while additional troops are welcome, Moscow’s involvement could become problematic. Russian interests don’t entirely align with the interests of a potential U.S.-led coalition. Both parties want to defeat ISIS. But Putin’s government is an ally of the same Assad regime that Washington ultimately wants ousted. Russia has reportedly bombed areas controlled by Syrian rebels supported by the United States.

Defense contractors, which have played a significant role in the United States’ most recent large-scale conflicts, might be a source of manpower in a new Middle East engagement.

A recent report from the Congressional Research Service says contractors “frequently averaged” 50 percent or more of the military’s total presence in Iraq and Afghanistan over the last decade. This summer, the Daily Beast reported that after the U.S. military’s withdrawal from Iraq, America had more contractors (6,300) than troops (3,500) stationed there. A majority of defense budget cuts in recent years have centered on support and command, which could exacerbate the need for contractors in future conflicts.

The military’s reliance on contractors, though, has been controversial. This year, a group of military contractors were convicted in federal court for the massacre of 31 innocent civilians in Baghdad’s Nisour Square in 2007. The federal government has said it failed to "provide effective management and oversight of contract spending" during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and admitted that contractor waste and fraud had cost U.S. taxpayers tens of billions of dollars.

One potential way to raise enough manpower and resources to alleviate readiness concerns and prosecute another full-scale war in the Middle East is through mandatory conscription and a war surtax. During the Vietnam War, there was a draft and a war tax — and in recent years, both ideas have been floated in legislative proposals from Democratic lawmakers.

“The all volunteer military was basically was designed for small type of operations -- if you get into a prolonged war you should activate selective service,” said Korb, who pressed his then-boss Ronald Reagan to keep the selective service system. “What I tell people is if you want to send lots of American troops back into the Middle East, let’s have a draft and raise taxes.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.