US Oil & Gas Fracking Boom Could Drive Silica Sand Mining Operations In 12 More States, Environmental Groups Say

Victoria Trinko says she hasn’t opened the windows to her home in Bloomer, Wisconsin, in more than two years. That’s around the time a mining company began churning up silica sand a half-mile from her family farm, filling the air with tiny particles and making it harder for her to breathe. “I could feel dust clinging to my face and gritty particles on my teeth,” Trinko recalls.

Silica sand is one of many ingredients used in the hydraulic fracturing process. During fracking, operators blast thousands of tons of sand and millions of gallons of water and chemicals into the ground to release oil and natural gas deposits stored in shale formations.

As fracking accelerates in the United States, demand for "frac sand" could climb 30 percent from 2013 to 2015, an increase of about 95 billion pounds of sand, according to industry projections. Sand miner U.S. Silica Holdings Inc. said demand for its own volumes of sand could double or triple in the next five years, Reuters reported last week.

In a report released Thursday, environmental groups and residents like Trinko said they are worried that expanding sand production will lead to increased health, air and water complications in communities near the mines. In Wisconsin and Minnesota, the states where most silica sand is produced, regulations are fairly lax for monitoring air pollution and water contamination at these sites, the groups said. Those states have more than 160 active fracking sand facilities combined, and another 20 projects are in the works.

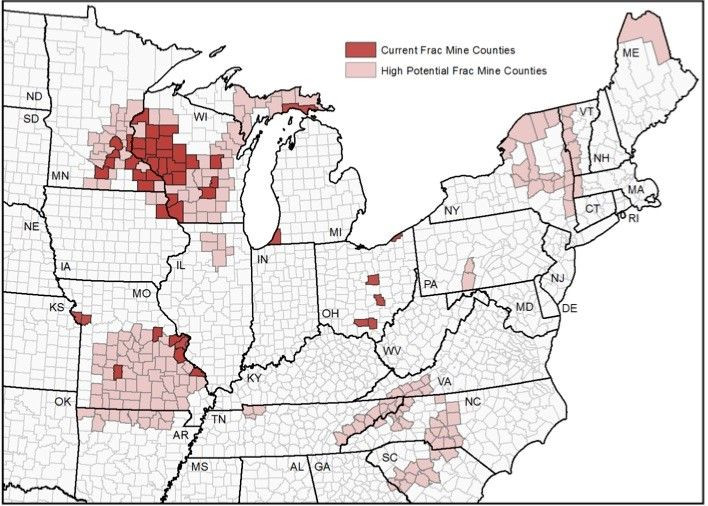

Given the pace of the fracking boom, silica extraction could spread to a dozen other states with untapped or largely untapped sand deposits, including Illinois, Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, Missouri, New York, North Carolina, South Carolina, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Vermont and Virginia.

Grant Smith, the report’s lead author, raised three key concerns with the expansion of silica production in any state.

First, water quality. Chemicals used in the mining process can enter the groundwater or surface water from dumping ponds at mining sites, raising the risks of contaminating drinking water supplies. Second, air quality. Small particles of silica dust can easily enter the lungs and bloodstream, and in the worst cases lead to silicosis, a lung disease. And third, financial effects. A major mining operation can depress nearby real estate values, and increased activity of heavy trucks and transportation equipment can shorten the lifespan of roads and bridges, requiring governments to pay for expensive repairs.

The rapid expansion of U.S. oil and gas drilling “has a hidden side filled with problems,” Smith, a senior energy policy adviser at the Civil Society Institute in Massachusetts, said in a call with reporters. For state and local governments, “health, water and other economic concerns should be addressed comprehensively, rather than just being ignored or dismissed.”

Spokespeople for the Wisconsin and Minnesota departments of natural resources were not immediately available for comment.

A related map published Thursday (see below) examined the impacts of existing mining operations. Researchers at the Environmental Working Group, a nonprofit advocacy organization, studied a 33-county area in southern Minnesota, southwestern Wisconsin and northeastern Iowa.

The area contains more than 70 sand mining operations and 27 sites for processing, transporting or loading sand onto trucks or rail cars -- a nearly 150 percent increase compared to just a decade ago. Another 82 mines or associated sites have been proposed or granted permits in the tri-state region.

Researchers found than more than 58,000 people live less than half a mile from existing, permitted or proposed facilities -- a range at which silica particles are known to degrade air quality. More than 162,000 people live within a mile of these sites.

“None of the states at the center of the current frac sand mining boom have adopted air quality standards for silica that will adequately protect those exposed,” Heather White, the group’s executive director, told reporters.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.