U.S. Opportunities In Libya And Egypt

Opinion

Events in Libya and Egypt highlight the potential benefits of United States human rights promotion -- both for the U.S. and for people across the world -- as well as the downsides of America's failure to pursue that task.

The U.S. promotes human rights -- i.e., freedom and democracy -- for both moral and selfish reasons. Morally, human rights promotion reflects the values we hold dear. Selfishly, we seek to advance freedom and democracy in order to help create a safer, more prosperous world from which we will benefit.

To promote human rights, Washington has a variety of tools at its disposal. The president can speak out forcefully for human rights, encouraging democratic activists while pressuring authoritarian governments; the president and Congress can allocate foreign aid to support democracies and withhold it from rights-abusing autocracies; and U.S. leaders can use military force to prevent or stop a government from slaughtering its people.

No one approach fits every challenge, so Washington must tailor its approach to every situation, choosing the most appropriate tools for the challenge at hand -- as events in Libya and Egypt make clear.

Needless to say, the Arab Spring (or Arab Winter, depending on your take) is a work in progress, one whose ultimate path may not be known for years. So, we should avoid definitive judgments about the direction of any particular country.

Having said that, the early signs in Libya are promising. The nation's recent parliamentary elections suggest that, despite widespread fears to the contrary, a nation once ruled by the maniacal Moammar Gadhafi has, at least at this point, largely rejected the Muslim Brotherhood and other extremist forces.

With 4,000 candidates vying for 200 seats in the General National Congress (which will form a government to replace the Transitional National Council), the National Forces Alliance (which supports a civil state) was maintaining its lead as returns continued to trickle in. To be sure, one election does not guarantee a democratic future. Nevertheless, the results to date raise justifiable hopes.

U.S. leaders, who have largely ignored the North African nation since the West's military action of last year helped topple Gadhafi, should not only be publicly applauding Libya's admirable progress. They should be offering financial and technical assistance to build the infrastructure of long-term democracy (civil society, opposition parties, a free press) while encouraging Libyan leaders to enshrine women's, minority, and other human rights into the laws and mores of their emerging society. That would make it harder for extremist forces to later seize power through non-democratic means.

Most Libyans admire America and our heritage of liberty, the Hudson Institute's Ann Marlowe wrote in the Wall Street Journal this week. That the United States, unlike Great Britain, France, and Italy, never cozied up to Gadhafi is a big part of the story.

Another big part is the military action that toppled Gadhafi (for which Washington provided the most important firepower). When New York Times columnist Nicholas D. Kristoff visited Tripoli after Gadhafi's fall, he wrote that Americans are not often heroes in the Arab world, but as nonstop celebrations unfold here in the Libyan capital I keep running into ordinary people who learn where I'm from and then fervently repeat variants of the same phrase: 'Thank you, America!'

U.S. leaders should return the favor, putting Washington squarely on the side of freedom and democracy by praising the progress to date and offering financial and technical assistance to help Libya achieve more.

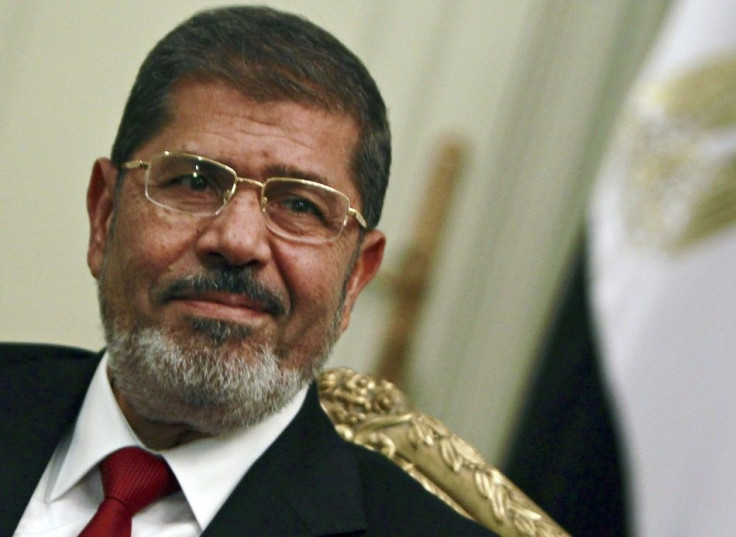

Perhaps understandably, U.S. leaders have focused their attention on fast-moving developments in Egypt, where military leaders are battling the nation's new president, Mohamed Morsi (the candidate of the Muslim Brotherhood), in a power struggle that the nation's top courts are trying to adjudicate.

For Washington, the challenge is much different in Egypt than Libya. Rather than reinforce pro-U.S. attitudes on the ground by further assisting a democratic transition, U.S. leaders must address a deep-seated skepticism among Egyptians that Washington is really interested in human rights at all.

For three decades, Washington backed strongman Hosni Mubarak as a pillar of stability in a turbulent region despite his disdain for human rights. That did nothing to engender warm feelings for the U.S. among the teeming masses of Egyptians who suffered under Mubarak's rule.

Now, as Egypt struggles to chart its path, Washington has another chance to position itself behind freedom and democracy. Whether it seizes the opportunity will depend largely on what President Barack Obama and his top diplomats do in the days ahead.

White House Press spokesman Jay Carney acknowledged that Obama would speak meet with Morsi during the UN General Assembly meetings in September -- though he suggested that their chat might not rise to the level of a formal bilateral meeting. Meanwhile, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton plans to visit Cairo this weekend, though the current power struggle could complicate her trip.

Whether Obama and Clinton meet with Morsi, however, is far less important than what they say during any encounter.

Will they make clear, publicly and privately, that Washington will put its voice, its money, and other resources behind efforts to build a free and tolerant society, one that permits free speech and free assembly, respects women and minority rights, and allows opposition parties and an independent media to flourish? Will they also make clear that Washington will oppose efforts that move in the opposite direction?

Or, will they succumb to an all-too-familiar U.S. pattern in the region, which is to sacrifice the cause of human rights at the altar of regional stability, enabling authoritarian governments to impose their will with impunity?

Obama, a self-styled foreign policy realist, has often avoided tough discussions about human rights when seeking better relations with rights-abusing regimes, whether in Beijing, Moscow, Tehran, or elsewhere. With so much up for grabs across the Middle East and North Africa, it's time for a course correction.

Egypt's people will be watching what we do. We shouldn't blow the opportunity.

Lawrence J. Haas, former communications director for Vice President Al Gore, is senior fellow at the American Foreign Policy Council and author of Sound the Trumpet: The United States and Human Rights Promotion (just out from Rowman & Littlefield).

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.