In US, Podcasts Can Sometimes Shape Course Of Justice

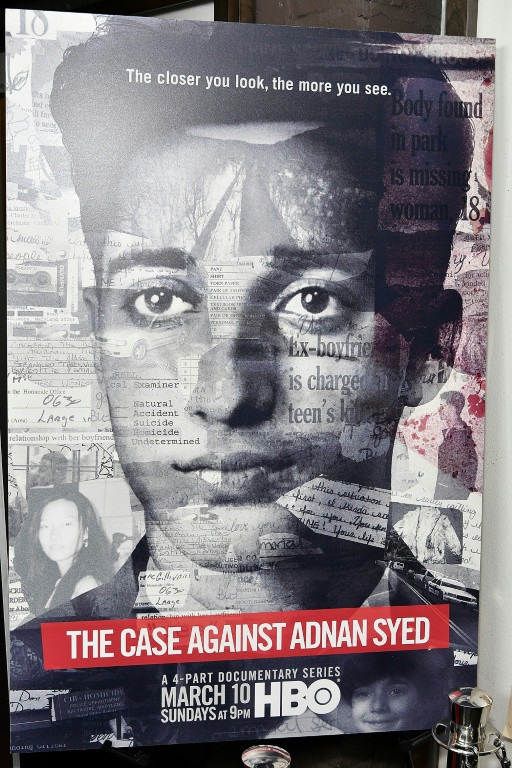

The release this week of one of the main characters on the hit podcast "Serial" has reignited the debate over Americans' "obsession" with true crime series and their effect on the US penal system.

When Adnan Syed walked out of the Baltimore courthouse free on Monday, 22 years after being given a life sentence for allegedly murdering his ex-girlfriend, a crowd of supporters greeted him with cheers.

Syed has always denied culpability in the 1999 murder of Hae Min Lee.

Among the supporters was Sarah Koenig, the journalist who in 2014 brought his case to the attention of millions of listeners with her podcast "Serial."

While she never concluded whether Syed was innocent or guilty, her investigation raised many doubts over how the case was prosecuted.

Downloaded millions of times, the podcast was "a pop culture hit," says Lindsey Sherrill, a communications researcher at the University of North Alabama and the author of multiple articles on the topic.

"People have been interested in true crime as long as we've had humans," she told AFP. "You can find evidence of people being interested in crimes even in the Middle Ages when people would go to see public executions and trials."

But with "Serial," it has transitioned from "something that was seen as kind of a salacious or guilty pleasure to something that's very accepted... So now it's cool."

Unsolved murders, failures of justice, mysterious disappearances -- podcasts dedicated to true crime have flourished in the wake of "Serial." Sherrill has counted at least 5,000 of them, although she says they vary in both nature and quality.

Most of them, made by amateur enthusiasts, do little more than "redo a Wikipedia article," Sherrill said.

But the higher-quality, "more impactful" ones are made by "journalists, or people involved in the law in some way."

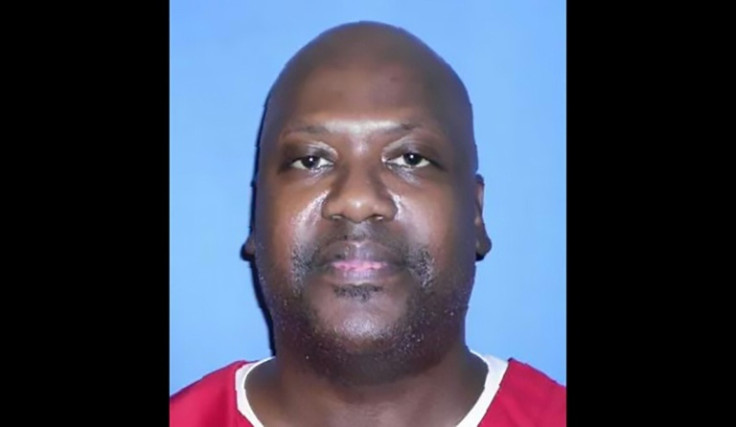

One of the best, in her opinion, is the second season of "In the Dark," a public radio show that examined the case of Curtis Flowers, a Black man tried six times for a quadruple murder that he has always said he did not commit.

The journalistic investigation, which pinpointed the failings of the lead prosecutor in the case, helped Flowers's legal team take his case to the US Supreme Court and helped secure his release after more than 20 years behind bars.

The effect of "Serial" on Syed's case is less direct, as prosecutors reopened his case as part of a request for a reduced sentence.

They have also retained the option to retry him. But in the United States, state attorneys are elected officials who are often attune to public opinion.

Sometimes, the amateur podcasts can have real effects, too.

The series "Truth and Justice," which encourages fans to send in tips, helped facilitate the 2018 release of Ed Ates, who was imprisoned for 20 years for the murder of a neighbor, which he always denied.

According to Dawn Cecil, a criminology professor at the University of South Florida, this participatory aspect is one of the main reasons for true crime podcasts' success -- along with their intimate nature and the ability to listen to an entire show in one sitting.

Listeners "can participate in online sleuthing and even crowdsource investigations, they can join social media groups to discuss cases and theories," she said.

But "it can create a whole host of issues if not done properly, such as false identification of suspects, interfering in ongoing investigations."

More broadly, while these shows are educational in nature and bring "more attention to potential injustices," they also have "a tendency to distort people's views of crime and justice," said Cecil, the author of "Fear, Justice, and Modern True Crime."

"Sending false messages about what crimes are most common," she explained, as well as "why people commit crime, who commits crime, and who is victimized, among other things."

Despite recent progress, many podcasts revisit the murder or disappearance of white women, often young and sometimes former beauty queens, such as the show "Up and Vanished."

The podcasts can also have a negative effect on the victims, especially if they don't want their story told, Cecil said.

The family of Lee, Syed's former girlfriend, has regularly said they are unable to move on because of all the attention on her case.

On Monday, her brother Young Lee let his pain explode while giving a statement over Zoom in court.

"This is not a podcast for me. It's real life," he said through tears.

"It's a nightmare."

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.