US Restarts Production Of Plutonium-238 After Nearly 3 Decades To Power Deep Space Missions

Earlier this year, it came to light that NASA had only enough plutonium-238 to drive not more than three batteries that currently power deep-space missions.

Now, to make up for the shortfall, the Department of Energy announced that 50 grams of the substance has been made at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) in Tennessee. While 50 grams is not a large amount, especially compared to the 4 kilograms of plutonium-238 the Mars 2020 rover would require, it marks the first time the material has been made on American soil in nearly three decades.

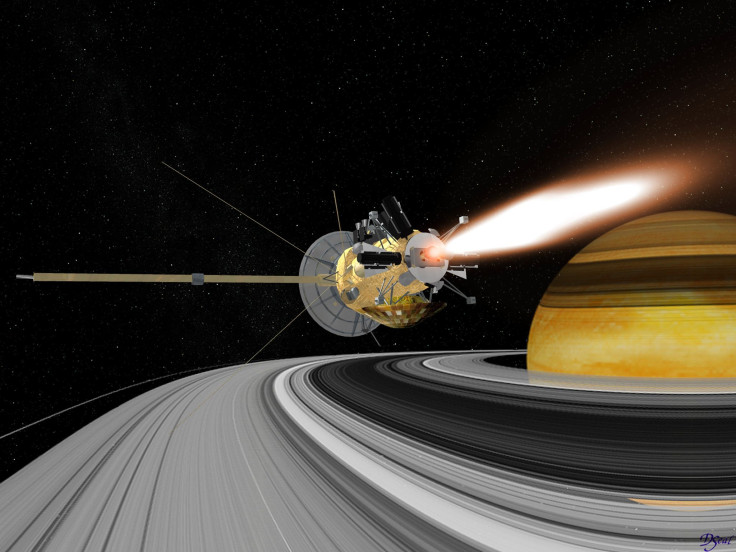

Plutonium-238 powers Multi-Mission Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generators (MMRTGs) -- the batteries used by missions such as Voyager, Curiosity, and New Horizons, and are manufactured by the DoE.

“This significant achievement by our teammates at DOE signals a new renaissance in the exploration of our solar system,” John Grunsfeld, associate administrator for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington, said, in a statement released Tuesday. “Radioisotope power systems are a key tool to power the next generation of planetary orbiters, landers and rovers in our quest to unravel the mysteries of the universe.”

The highly radioactive plutonium-238 is different from the plutonium used in nuclear weapons and power stations. As plutonium-238 decays into uranium-234, it gives off huge amounts of heat, which can then be converted to electrical energy by NASA’s radioisotope thermoelectric generators. Additionally, the heat also keeps scientific instruments warm in the cold void of space, allowing them to function properly.

Right now, though, NASA only has an estimated 35 kilograms of plutonium-238, of which only 17 kilograms is believed to be of a quality suitable for use in spacecrafts. And, in the statement, the DoE said that it hopes to scale up the operation to produce an average of 1.5 kilograms of plutonium in the coming years.

“As we seek to expand our knowledge of the universe, the Department of Energy will help ensure that our spacecraft have the power supply necessary to go farther than ever before,” Franklin Orr, under secretary for science and energy at the DoE, said. “We’re proud to work with NASA in this endeavor, and we look forward to our continued partnership.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.