US Solar Boom: 'Community' Solar Energy Projects Are Accelerating America's Drive Toward Renewables

Americans are putting more solar panels on their roofs than ever before. Yet only a small group of people -- homeowners, mostly well-to-do -- are driving the boom. Apartment dwellers, cash-strapped families, renters and others are largely shut out of the solar movement, sidelined by financial and technical constraints.

Enter community solar projects.

Paul Hyun and his neighbors have one of them on their rooftop. They live in a 70-unit apartment complex in a tightly packed neighborhood in the Brooklyn borough of New York. A solar array is affixed to the roof, and each neighbor pays about $80 a month to cover the cost of installing and maintaining the system. All the electricity that’s produced is sold to the local utility, Consolidated Edison Inc., and the neighbors split the proceeds.

Hyun said he typically saves 15 to 30 percent on his electric bills thanks to the solar panels. In January, he received a $1,000 rebate check from the housing cooperative, which manages the project.

“When I talk to my neighbors in other buildings, a lot of them are jealous of what we have,” said Hyun, a real-estate agent in Sunset Park.

Shared solar arrays are a tiny but growing segment of the broader U.S. solar market. As demand for cleaner and cheaper energy rises, more residents are finding alternative ways to access renewable energy -- even when they don’t own homes or have deep pockets.

Such projects are critical for accelerating the nation’s overall use of lower-carbon energy, analysts say. More than three-quarters of U.S. homeowners can’t put up panels because their roofs are positioned wrong or the costs are too high. Even fewer renters, public-housing residents or condo owners can go solar due to building restrictions.

Through shared arrangements, solar companies and utilities can tap into an otherwise overlooked demand segment, said Cory Honeyman, a senior analyst covering U.S. solar markets at GTM Research in Boston.

“Community solar is one of the next largest growth market opportunities in the broader U.S. solar market,” the analyst said.

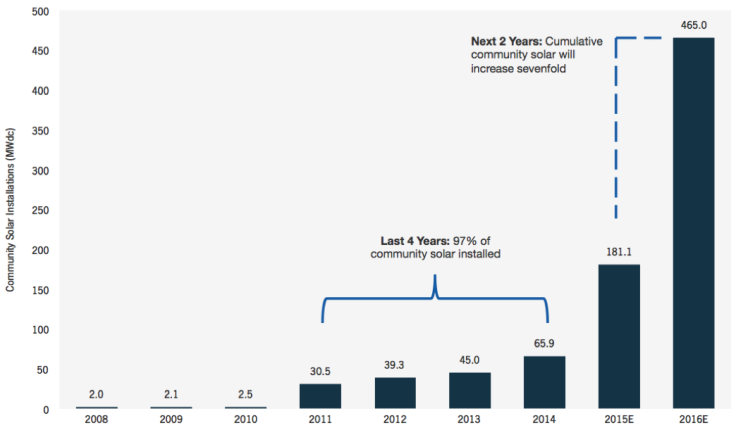

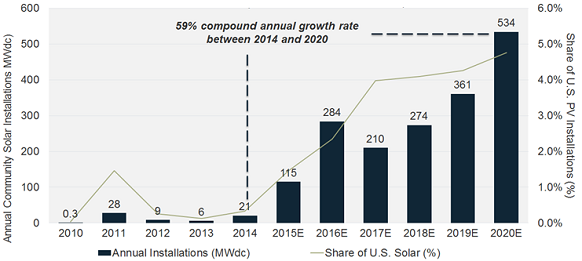

Installations of shared solar projects are expected to total 115 megawatts in capacity this year, a jump of nearly 75 percent over last year’s additions, according to GTM Research. In 2020, neighbors and business owners could add 500 megawatts of community solar, or about 5 percent of total solar installations that year.

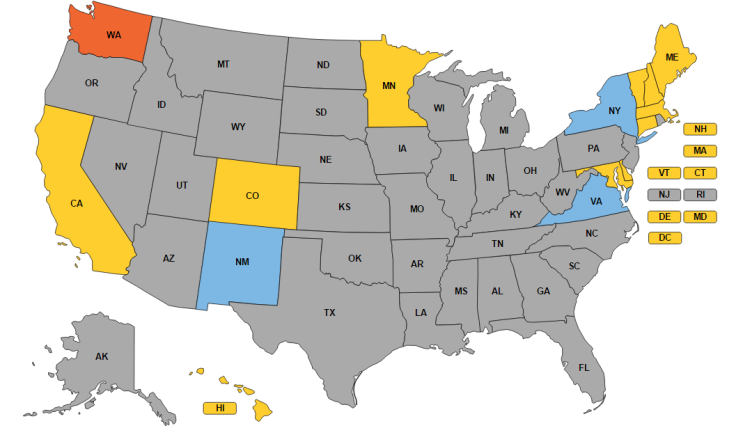

Favorable policies and incentives in a dozen states and the District of Columbia are driving much of the growth in shared solar-project ownership, and at least four other states are considering adopting similar rules. Major players in the rooftop solar space, such as SolarCity Corp. and SunEdison Inc., are extending their third-party financing programs to community projects.

Most recently, the Obama administration this week unveiled a plan to help low- and middle-income Americans gain access to solar energy, including a low-cost loan program for homeowners and a nationwide initiative for renters.

Elizabeth Kennedy, the solar-program director at the Massachusetts Clean Energy Center, said her agency is exploring more ways to help residents invest in the community solar space.

Massachusetts’ first shared solar project was developed in 2011 by a group of 50 residents in the town of Harvard, Kennedy said. The state-run agency was rolling out a program to help cut the costs of rooftop solar projects, but not everyone could participate. Their houses were considered historic landmarks, faced the wrong way or were surrounded by too many trees. “Those residents banded together and worked with a local installer” to build their own joint solar array, she recalled. “There’s such a community aspect to it.”

While these projects benefit residents who couldn’t otherwise access solar, the shared nature of these arrays has its own drawbacks. Community projects tend to be larger than the typical single-home solar system, so they take longer to design, develop and permit. They also require participation by dozens or hundreds of people to drive down the costs for individuals.

“Sometimes, there’s a bit of a chicken-and-egg problem,” Kennedy said. “The developer wants to build a community shared solar project, but you have to line up a critical mass of interested customers in order to do that.”

GTM Research’s Honeyman said participants in shared solar projects tend to save less on their monthly electric bills compared to homeowners with individual systems. In some communal projects, participants may see no savings at all, unless the price of traditional electricity begins to rise substantially.

But with lower savings comes lower risk, Honeyman said. Homeowners or businesses with their own arrays can’t pluck the panels off their rooftops when they move, as each has to sell the solar apparatus with the building. Individual owners must deal directly with solar developers. For Hyun in Brooklyn, his solar investment is hands-off: He sends in a monthly check to the housing cooperative, and the rest takes care of itself.

“There’s less headaches that come with participating in community solar than participating in rooftop solar,” Honeyman said.

Shared solar projects are still just a tiny slice of the nation’s broader solar market. Of the 6,200 megawatts of solar photovoltaic projects installed last year, only about 1 percent was considered community solar, GTM Research data show.

Nonetheless, Honeyman said the market is now gaining steam. Beyond 2020, community solar could grow exponentially and eventually beat out the residential, commercial and utility-scale solar sectors. “There’s an increasingly strong case for post-five years from now ... of it being the leader of new solar development,” he said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.