U.S. Supreme Court Wrestles With Oklahoma Tribal Dispute In Breyer's Last Case

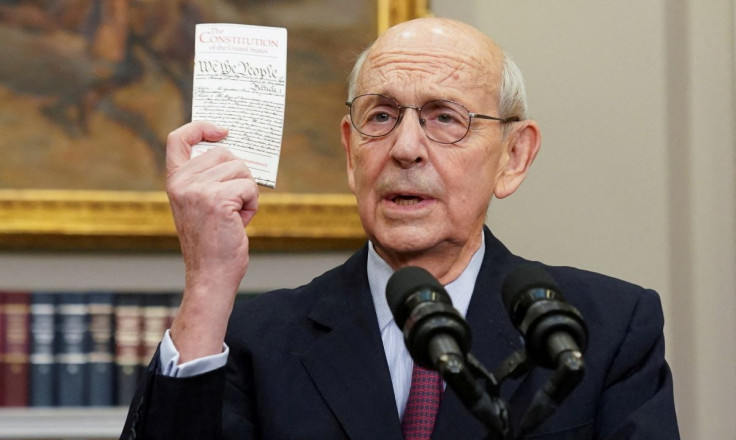

The U.S. Supreme Court on Wednesday, in Justice Stephen Breyer's last scheduled oral argument before retirement, appeared divided as it weighed limiting the impact of its own 2020 ruling that greatly expanded Native American tribal authority in Oklahoma.

The justices heard Oklahoma's appeal in a case involving Victor Castro-Huerta, a non-Native American convicted of child neglect in a crime committed against a Native American child - his 5-year-old stepdaughter - on the Cherokee Nation reservation.

A state court threw out Castro-Huerta's conviction, saying the Supreme Court's 2020 ruling deprived Oklahoma authorities of jurisdiction in his case.

Breyer, at 83 the oldest of the nine justices, announced his retirement in January, effective at the end of the court's current term. The Oklahoma case is the last one on the argument calendar, with the justices expected to finish issuing rulings for the term by the end of June. The Senate on April 7 confirmed Ketanji Brown Jackson, Democratic President Joe Biden's pick as the first Black woman to serve on the court, as Breyer's replacement.

Chief Justice John Roberts, at the argument's conclusion, expressed his "deep appreciation of sharing the bench" with Breyer, who joined the court in 1994.

The 2020 ruling in a case called McGirt v. Oklahoma recognized about half of Oklahoma - much of the eastern part of the state - as Native American reservation land beyond the jurisdiction of state authorities. The ruling, criticized by Governor Kevin Stitt and other Republicans, meant that many crimes on the land in question involving Native Americans now must be prosecuted in tribal or federal courts.

The state prosecutes crimes in which no Native Americans are involved in the affected land.

Tribes have welcomed the McGirt ruling as a recognition of their sovereignty. The Supreme Court in January rejected Oklahoma's request to overturn it.

The new case focuses on whether non-Native Americans who commit crimes on Native American land against Native Americans should remain under state jurisdiction. As a result of the McGirt ruling, such crimes - about 3,600 every year - will now be prosecuted by the federal government.

In the 5-4 McGirt ruling, conservative Justice Neil Gorsuch joined four liberal justices and wrote the decision. Since then, the court has moved rightward, with conservative Justice Amy Coney Barrett replacing the late liberal justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg in 2020, leaving a 6-3 conservative majority. Barrett, who expressed some doubt about Castro-Huerta's arguments, may now cast the deciding vote.

Gorsuch said it had long been understood that states do not get jurisdiction over such cases, citing the history of state discrimination against Native Americans. In Oklahoma, state courts played a role in depriving Native Americans of property rights when oil was discovered, Gorsuch pointed out.

"The history and the reality should stare us all in the face," Gorsuch said.

Breyer noted that if the court limits the scope of the McGirt ruling in Oklahoma, it also would upend the law in the 49 other states where the "general assumption" has been that they do not handle the prosecutions of crimes against Native Americans on land under Native American jurisdiction.

"Now you are creating chaos across the country," fellow liberal Justice Sonia Sotomayor said of that potential outcome.

Some conservative justices who dissented in the 2020 decision seemed sympathetic toward Oklahoma's argument.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh expressed concern about crimes against Native Americans not being prosecuted because of a lack of federal resources and questioned whether a ruling against Oklahoma would help tribal interests

"I don't see how it would help Indian victims. It's going to hurt Indian victims," he said.

The eventual ruling, due by the end of June, will not affect cases heard in tribal courts involving crimes committed by and against Native Americans.

Castro-Huerta was convicted in state court of neglecting his stepdaughter, who has cerebral palsy and is legally blind, and sentenced to 35 years in prison. The Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals last year threw out that conviction. But Castro-Huerta by then was already indicted for the same underlying offense by federal authorities, transferred to federal custody and pleaded guilty to child neglect. He has not yet been sentenced.

© Copyright Thomson Reuters 2024. All rights reserved.