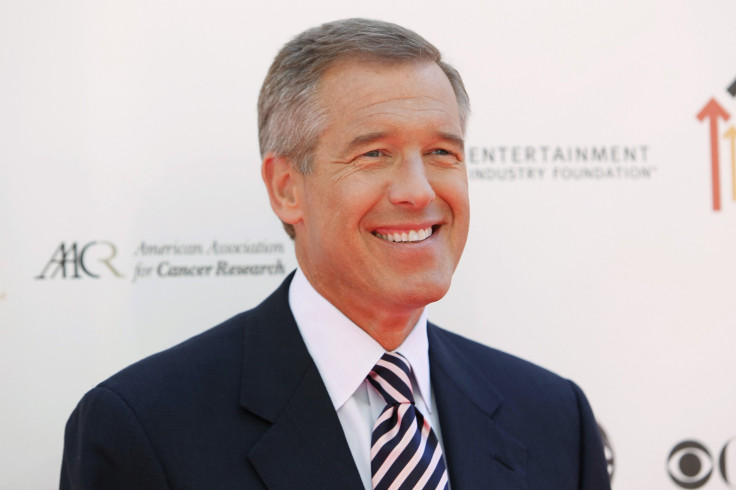

Veterans Slam Brian Williams' Iraq Story, But Say Scandal Shouldn't Detract From Value Of Embedded Journalism

NBC News anchor Brian Williams' fabricated tales about his reporting stint with a U.S. military unit have angered veterans who say he broke their trust and lied about his experience in Iraq for nearly 12 years. Williams, they say, was welcomed by the military under a longstanding tradition of embedded journalism, where service members protect reporters who often have few military skills with the hope that their harrowing tales of battle and bravery will be told. But Williams' subsequent betrayal violated the military's code of honor, veterans said.

Anthony Anderson, a South Carolina Army veteran who owns the Guardian of Valor site, which exposes people for lying about their military records, said he wasn't impressed by Williams' apology this week because it came only after the famous journalist was hounded by troops. "It took him 12 years," Anderson said. "He knew what he was saying. He knew that he was lying. You just don’t remember getting shot at, and I think the soldiers that were actual there saying, 'Hey, you weren’t there,' for him to apologize the way he did, it made it worse in the veterans community. Had they not come forward, I really don’t think he would have admitted to lying about it."

Williams had long claimed that he was aboard a Chinook helicopter hit by two rockets and small arms fire during the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003. But it was revealed this week that Williams was actually never in danger. Instead, he arrived at the scene in a separate helicopter about an hour later.

“On this broadcast last week in an effort to honor and thank a veteran who protected me and so many others following a ground-fire incident in the desert during the Iraq War, I made a mistake in recalling the events of 12 years ago,” Williams said in an on-air apology Wednesday night. “It didn't take long to hear from some brave men and women in the air crews who were also in the desert. I want to apologize: I said I was traveling in an aircraft that was hit by RPG fire. I was instead in a following aircraft. We all landed and spent two harrowing nights in a sandstorm in the desert. This was a bungled attempt by me to thank one special veteran, and by extension our brave military men and women - veterans everywhere -- those who have served while I did not. I hope they know they have my greatest respect … and also now my apology.”

Williams elaborated on Facebook after he was pressed by angry veterans. “You are absolutely right and I was wrong. In fact, I spent much of the weekend thinking I'd gone crazy. I feel terrible about making this mistake, especially since I found my OWN WRITING about the incident from back in '08, and I was indeed on the Chinook behind the bird that took the RPG in the tail housing just above the ramp,” he wrote. “Because I have no desire to fictionalize my experience (we all saw it happened the first time) and no need to dramatize events as they actually happened, I think the constant viewing of the video showing us inspecting the impact area -- and the fog of memory over 12 years -- made me conflate the two, and I apologize.”

Williams embedded with a U.S. military unit at the start of the Iraq War, a popular practice at the time that raised questions about the media's objectivity while reporting on the conflict. While embedded, journalists often become part of the unit's family, sharing in the service members' fear and excitement, veterans said. For the most part, both sides admire each other, forming strong relationships.

"There’s a lot of journalists out there that we respect," Anderson said. "This is the first time I’ve actually run across anything where a journalist's story was brought into question."

Bryan Nesfeder, who served in the Marines from 1999 to 2011, including in Iraq and Afghanistan, said journalists deserve credit for reporting from dangerous conflict zones.

"It’s very important to embed reporters. It’s brave of them and there is a message that needs to be brought back to the people, and that’s the best way to do it," said Nesfeder, who founded vetprestige.com, a career networking site for veterans. "These reporters kind of become part of the unit’s family. The unit protects them, and they are there to tell the stories."

Nesfeder said he was having a hard time understanding how Williams could repeat an untrue story for more than a decade. "Adopting a memory is a strange term. It’s not something I can completely comprehend. I think your memory is very clear about what happened, but who’s to say?" Nesfeder said. "The true heroes of any given day don’t beat their chest about it. They are usually very, very humble."

Other veterans also said lying about your time overseas with the military is obviously frowned upon.

"For the most part, journalists are respectful. I think for the majority of those who’ve embedded or spent any time with troops in a hot zone, the gravity of the situation is intense enough. They don’t need to add color," Randi K. Law, spokeswoman for the Veterans of Foreign Wars' national office in Missouri, said in an email. "Mr. Williams’ embellishment shows he has no idea what the term 'direct fire' really means. Whatever personal or professional fallout that follows will and should be determined by the American public."

American Legion National Commander Michael Helm was also not ready to forgive Williams. "As an organization of wartime veterans, the American Legion finds Mr. Williams’ behavior reprehensible, and it shows a marked lack of integrity and character," he said in an emailed statement Friday.

Williams certainly wasn't the first to lie about his wartime experiences, but each fabricated tale is still hard to understand, said Anderson.

"I get asked that a lot, why do these people do what they do?, and I really don’t have any answer," Anderson said of people who tell military tall tales. "Some do it to get the attaboys, some do it for financial gain. Whether he did it to help his career, I don’t know."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.