Wall Street Meets Climate Change With Fossil-Free Exchange-Traded Fund

Investors looking to ditch their stocks in high-carbon U.S. companies can steer their dollars to Etho Capital's soon-to-be-launched, first-of-its-kind investment fund. The fund eschews fossil fuel producers entirely and considers only companies with cleaner-than-average carbon footprints.

The Etho exchange-traded fund (ETF), which will start trading on the New York Stock Exchange next week, includes 400 publicly listed companies from a diverse mix of industries, including healthcare, IT, manufacturing and consumer goods. Etho Capital says it narrowed the list to businesses that are taking the biggest strides to reduce harmful greenhouse gas emissions while still delivering strong financial returns for investors.

“It’s still a commonly held belief that sustainable investing means you don’t care as much about your financial performance,” said Ian Monroe, co-founding president and chief sustainability officer at Etho Capital in San Francisco. “Our mission is to create the world’s best fossil-free investment products that are superior in terms of overall sustainability and financial performance.”

The climate-focused ETF is the latest outgrowth of the so-called “impact investment” movement. U.S. and global investors -- especially millennials in their late 20s and early 30s -- are increasingly gravitating toward funds and companies that reflect a broad range of values, including lower environmental impacts, strong human rights records and decent wages for workers. About 71 percent of individual investors say they’re interested in these types of investments, the Morgan Stanley Institute for Sustainable Investing found in a February survey.

Climate issues in particular are gaining attention in financial circles in the run-up to the United Nations climate change conference in Paris, which starts Nov. 30. Negotiators from nearly 200 countries have agreed to forge a deal to reduce global emissions sharply and help the most vulnerable nations adapt to rising sea levels, brutal drought and other climate effects.

In the last year, a growing number of financial institutions and companies -- including major European oil and gas producers -- have joined calls for a price on carbon dioxide emissions, which would make it costlier to burn and consume coal, oil and natural gas. Large investment funds are steadily pulling their money out of fossil fuels: In February, Norway’s $850 billion Government Pension Fund Global, the world’s richest sovereign wealth fund, said it had ditched 114 companies on environmental and climate grounds. Last month, California Gov. Jerry Brown signed a law requiring the state's two largest pension funds, Calpers and CalSTRS, to sell their investments in about two dozen thermal coal mining companies.

“There’s definitely been a trend toward being fossil fuel-free or low-carbon,” said David Kathman, a senior analyst for Morningstar, an investment research company.

Responding to that trend, Morningstar said in August it would launch the industry’s first system to score global mutual funds and ETFs based on their performance on environmental, social and governance criteria. “There’s rising interest. People are looking for that type of information,” Kathman says. The scores could be published in early 2016, he adds.

Etho Capital’s new fund isn’t the only ETF to exclude fossil fuels. Other specialized funds, such as those focused on renewable energy or healthcare, exclude oil producers or coal miners by definition. But Monroe says the Etho ETF is the first broad-based fund spanning multiple U.S. sectors that doesn’t include fossil fuel companies or related firms, such as pipeline builders or gas distributors.

Monroe formed Etho Capital last year with his co-founders after launching the startup Oroeco, which makes an online platform to help users improve their carbon footprints. “We saw it could be used to create investment funds optimized for climate and financial performance,” Monroe recalled. Etho Capital in October launched its Climate Leadership Index, which tracks lower-carbon equities and provides the foundations for the upcoming ETF.

For the Etho fund, the California investment firm reviewed 5,000 of the most commonly traded public companies and compared their total greenhouse gas emissions -- including those from direct operations, electricity use and supply chains -- with their total market values. Etho Capital then determined each firm’s “climate efficiency”: the level of emissions associated with every dollar invested.

“If you’re a shareholder in that company, if you own ‘x’ percent, then you’re responsible for that same percentage of the company’s emissions,” Monroe said. Compared to the S&P 500 index, the 400 final companies in the Etho ETF average 50 percent fewer emissions per dollar invested, according to Etho Capital.

Firms in the ETF were also screened to exclude certain taboo industries, including tobacco, weapons and gambling, as well as companies that scored poorly in other measures of social responsibility and sustainability. For instance, agribusiness giant Monsanto Co. did not make the cut -- despite a good climate efficiency scoring -- because of various controversies surrounding its use of genetically modified seeds and a recent World Health Organization finding that Monsanto’s RoundUp pesticides probably cause cancer in humans.

Conor Platt, Etho Capital’s co-founding CEO and chief investment officer, said the ETF is only the first of multiple climate efficient financial products the company plans to develop in coming years. The executives will appear on Wall Street next month to ring the bell at the New York Stock Exchange.

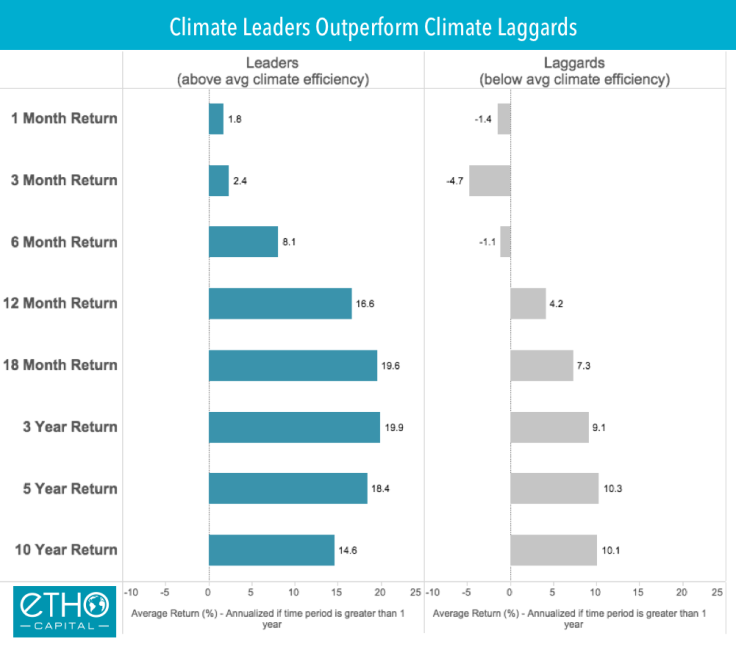

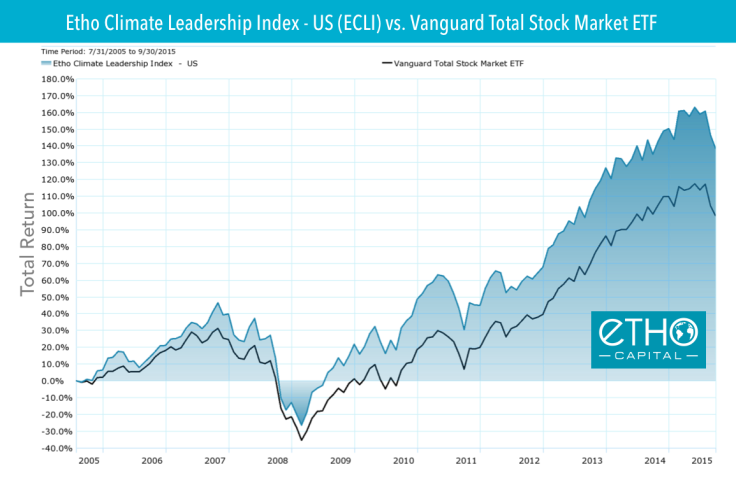

Etho Capital said its list of climate leaders outperformed the “laggards” -- companies with below-average efficiency scores -- for financial returns over periods from one month to 10 years. The Etho ETF also performed better than the Standard & Poor's 500, a common benchmark for the U.S. stock market, on a risk-adjusted basis over the last decade, the firm said.

“Investing in the most efficient companies in each industry appears to improve financial returns and improve your risk profile,” Monroe said.

Kathman, the Morningstar analyst, said the reality is much more complicated. He analyzed a handful of recent studies on the performance of environmental and socially oriented funds and found that, on the whole, they aren’t too different from the rest of the market. “There are some good [sustainability] funds and some bad ones, and they as a group will outperform some of the time, and underperform other times,” he said. “It seems to not make that much of a difference, either positively or negatively.”

Skeptics of impact investing tend to note its tiny scale in the broader financial markets even with the surge of interest in recent years.

“I’m aware this is still a rounding error on the capital markets. It’s a few billion dollars versus a few trillion,” said Matthew Weatherley-White, co-founder and managing director of The Caprock Group, a family wealth-management firm focused on impact investing.

Weatherley-White launched the advisory firm in 2005, after growing disgruntled with Wall Street while working at SmithBarney, a brokerage firm that later merged with Morgan Stanley after the 2008 financial crisis. “I felt this subtle but pervasive existential disappointment in the capital markets, and the way they prioritized financial returns over everything else,” he recalls.

He said despite the niche role of impact investing, he expects it eventually could become the norm as more shareholders and consumers let moral values guide their decisions. “It will be just as laughable to invest with disregard for social or environmental consequences as it was [unthinkable] in the 1950s to hire children to work in shifts at a factory,” Weatherley-White said. “In 20 years, maybe sooner, impact investing will fade and will simply become investing.”

A similar transformation is taking place within many companies themselves. If executives at first chased “green” projects to boost their public image, many are now pursuing sustainability strategies to enhance their bottom lines. Ford Motor Co., for instance, has said it cut total water consumption by 62 percent from 2000 to 2014, in large part to insulate the Detroit automaker from rising water costs, scarcer resources and tougher regulations.

“We have boards of directors actively asking their CEOs what their sustainability plans are. Young employees are using sustainability as a way of deciding where they’d like to work and not work,” said Rick Fedrizzi, chief executive and founding chairman of the U.S. Green Building Council, a nonprofit organization that runs the LEED green building ratings system.

In his book “Greenthink,” Fedrizzi argued capital markets could “save the planet” as companies and investors shift to operations that burn fewer fossil fuels, consume fewer natural resources and use energy more efficiently. “It’s really about the idea that it’s OK to be a capitalist and an environmentalist,” he said. “You can have tremendous financial performance of your company or your job, and you can be an increasingly responsible environmental citizen.”

Platt of Etho Capital said the next few months will serve as “the big testing ground” to see how individual and institutional investors respond to the firm's Etho ETF. The goal, he added, “is to make this mainstream.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.