'This War Of Mine' Review: The Indie Game Topping Steam's Sale Charts

“This War of Mine” has garnered lots of press attention as a war game that has you assuming the roles of noncombatants. It’s been pegged as a thinking and time-management survival game, a moral simulator that puts the faces of real people to war. You play a real person trying to survive rather than the role of supersoldier #28 who can miraculously heal his wounds by hiding behind a wall for five seconds.

Two weeks after its release, it remains at the top of the Steam download charts, even atop titans like "Call of Duty: Advanced Warfare" (though the main "Call of Duty" fan base is console-driven).

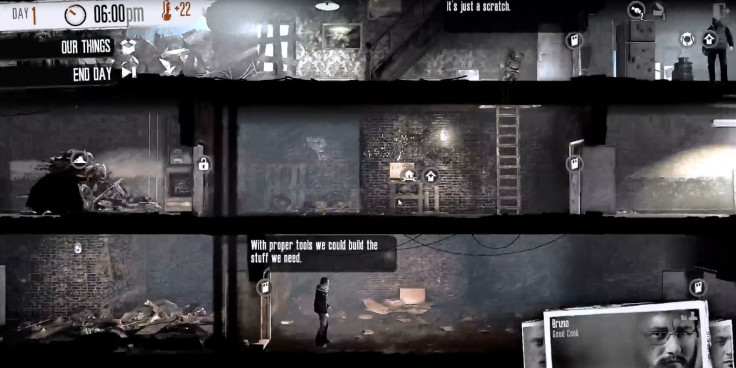

At its core, “This War of Mine” is a survival and resource-management game mixed with some light platforming. The only way to interact with anything (or anyone) is your mouse’s left click.

It’s a difficult experience, in more ways than one.

You start with a random trio of survivors. No blood relation to one another, just people who have banded together to stand a better chance in their war-torn country. The characters have a basic shelter full of holes and rubble, pieces of the walls blown away by mortar rounds. There are very limited supplies inside, so they’ll have to get to work quickly if they want to stay alive. The group must venture out to restock.

That’s where the experience truly begins -- your group isn’t the only band of survivors in the city. Not everyone is friendly. Those who are might trade with you. Some will try to join your group, adding another mouth to feed in an environment bereft of food. Some will ask for handouts. Not all can survive.

“This War of Mine” tests your moral compass: How do you treat other survivors? Do you steal from the innocent to ensure your band lives another day? Do you stand with strangers to fight back against the military that abuses its citizens, or do you ignore injustice? No one is immortal, and everything you do has consequences, both good and bad.

And “This War of Mine reminds” you of that at every turn.

I sent one of my group members, Pavle, to scavenge through the abandoned supermarket in search of food we desperately needed. Reports had suggested the area was dangerous, so I gave Pavle a homemade knife, just in case. As he searched through the shelled store, Pavle overheard a conversation between a male soldier and a female scavenger. Initially, the soldier was somewhat friendly, offering to help the woman look for what she needed -- food. When she politely declined his help, he then offered to give her food and wine in exchange for sex.

She refused. He pushed her toward a wall, trying to take her by force.

Pavle had been watching the scene through a crack in a door. He had his knife in his hand, though he was not trained in combat; he was an athlete before the war. I asked him to approach the armed soldier, knife drawn. Pavle burst through the door, giving the unnamed woman a chance to run. As the soldier raised his rifle toward Pavle, I ordered my survivor to stab him.

The soldier did not collapse after the first clumsy slash, and raised his rifle once more. Another slash. The soldier yet lived, but he did not raise his weapon a third time. Instead, he begged for his life.

Pavle’s makeshift blade pierced him a third time. The soldier would never terrorize civilians again.

But I had a choice: leave the soldier wounded and risk retribution from the overbearing military, or eliminate the man to ensure brutal justice and safety. I was tired of seeing innocent people struggle. It felt empowering to take his life in a way no "Call of Duty" shot to the head ever had.

When Pavle returned to our hideout, he told the others what happened at the supermarket. He was glad that he had saved the girl, as were the others -- it gave them a sliver of hope that the people weren’t totally powerless. They felt no remorse for the would-be rapist lying in a poolof blood.

Word traveled quickly, it seemed. A new survivor, Zlata, came to our door the next day. She sought asylum and had heard that we were a friendly bunch. We accepted her, albeit reluctantly; Zlata was a musician and lifted our spirits, but she was also another mouth to feed. The following evening, I sent another survivor, Katia, to a derelict house to look for food (Pavle, though proud of himself, needed a rest).

I gave Katia the same shoddy shovel she’d used to clear out piles of debris in the hideout, in case she ran into any roadblocks on the expedition. And in case a hostile party was already there, the shovel could be a blunt force weapon. But Katia did not encounter any resistance at the house as she searched and scavenged for a few hours in the middle of the night. She found a note from an artist in a desk, saying that he would not leave until his painting was finished. Where someone would even get painting supplies in a time like this was beyond her. It did not matter. Katia resumed her search, entering the basement. There she found (presumably) the artist from the note. He was not hostile.

He was hungry.

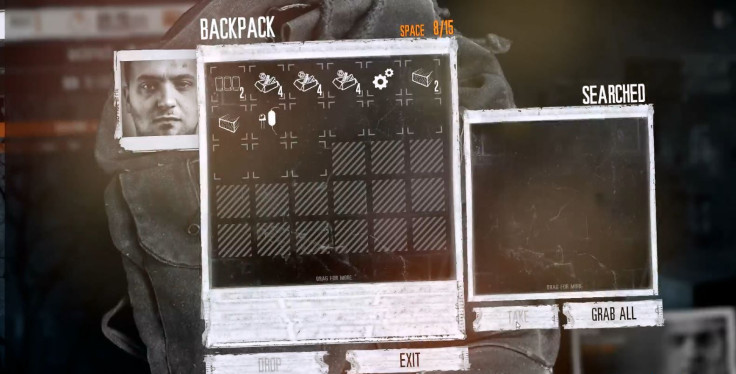

He had not eaten in days. He pleaded with Katia for food, saying that she “seems like a nice woman.” There was no food in the house, and I hadn’t given Katia any to bring along. Why would I? Food would have just taken up space in her backpack. Although I felt bad for the man, I had to leave him empty-handed. He hoped Katia would return soon with food. Katia felt guilty. She returned a few days later, with a few pieces of food we could spare.

The artist was dead.

Maybe he was beyond help when Katia first met him, maybe not. It still felt like we could have saved him. Katia was upset that she could not help.

Either way, we had to move on. A plane had dropped humanitarian aid packages all over the city, and though the military had already confiscated the vast majority of them, a neighboring survivor had secured one stash. He offered to share some of the haul with us if we helped carry supplies to his hideout. I sent Pavle, and he returned the next morning with much-needed stocks of fresh meat and vegetables.

Soon the fighting within the city cut off access to multiple scavenging points. The ones that were left would force us to either kill heavily armed, deranged militiamen or steal from the church congregation.

I chose to send Pavle to the hotel, to look for food. We had run out, and I was unwilling to steal from innocents to assure our survival. We would not lose our humanity so quickly. Instead, Pavle would sneak around, hoping to find some useful things in the ruins.

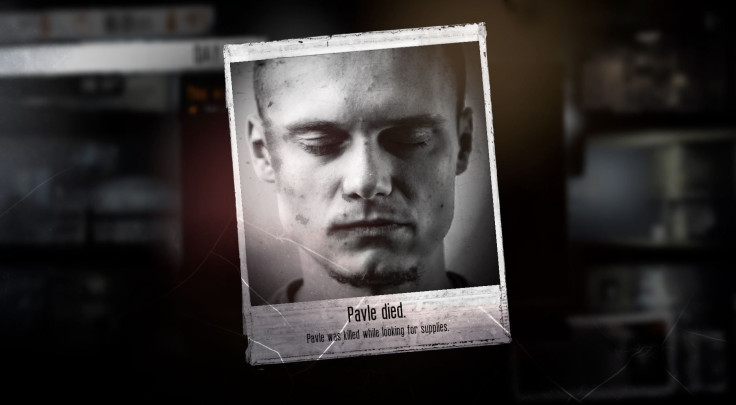

Instead, Pavle would die.

Pavle found the mutilated bodies of two people in a quiet spot of the hotel. The information had said screams came from this building at night, presumably from these unlucky souls. He stumbled upon a locked room at the top of the hotel, where the militiamen had been keeping their next victim. He tried to open the door quietly, but one of the militiamen heard him from the floor below and opened fire. Although Pavle retreated to a dark corner, the gunman alerted his brothers, and Pavle was soon cornered by four heavily armed assailants. There was a hole in the wall that led outside, but Pavle was four stories up -- to jump would be suicide. So he waited until all but the original gunman had left the floor, and charged him with his knife. Pavle’s life ended with one well-placed bullet to the chest. Pavle was not a soldier, and nothing I tried to have him do would make him a match for one. He never stood a chance.

He died because he tried to help his fellow man.

News reached the hideout. Pavle was not coming back. Katia and Zlata were devastated. Bruno, my cook who never ventured outside, promised himself that he wouldn’t die the same way.

It was at this point, though I still had three people left, that I had to step away from “This War of Mine.” Although the characters you control never get elaborate story arcs, they get just enough backstory for you to grow attached. They feel like regular people, struggling to eke out one more day in a miserable hellhole of a reality. The odds are against them, and it’s ultimately up to you to keep them alive. There are no redos, no checkpoints, no multiple save files. Once you make a decision, you are stuck with the repercussions.

“This War of Mine” crushes the ego. We are used to being gods in war games: infinite lives, recharging health, properly equipped and trained soldiers. Yet here, we watch our comrades die for a can of food or a few vegetable scraps. Or for just trying to do the right thing. It’s not fair.

That’s what makes “This War of Mine” so difficult. And as a sheer emotional experience, it’s hard to top.

For those wondering, there is an ending to the game. Provided you can survive long enough, there may be a cease-fire, temporarily ending the war. You don’t win “This War of Mine” in a traditional way.

“This War of Mine” was reviewed on PC, with a code provided by 11 Bit Studios/Evolve PR.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.