We're Not Alone Here: Death Unites Us All In Mourning

“A father should never have to bury his son.”

When I was young, my father told me that when we heard news of a young man’s death. We didn’t attend the wake or the funeral, but the message still stayed in the back of my mind.

I wondered how my parents would cope if they had to put me in the ground, instead of me burying them. Moreover, I wondered what the funeral was like - I had been to my grandfather’s, but I was a child at the time. I didn’t understand the emotion involved with the ritual; to me, grandpa had expired and was being put away. Kind of like milk.

But you’re never surprised to hear an old man died.

Kyle Miller was 18.

His father buried him the week before Christmas, on a beautiful, crisp December morning. The atmosphere above the church enveloped our town with a grey-white blanket to match the somber mood of the funeral attendees as we watched Kyle’s casket loaded into the back of the waiting hearse.

Everyone was surprised when Kyle’s car hit a telephone pole. But we thought he’d pull through - kids aren’t supposed to die. You just expect them to bounce back, because teenagers are made of rubber and magic. They can stay awake all night on a Red Bull and go to work the next morning without a hitch. Some scrapes and bumps from a car accident should be no big deal, right? He’ll be back at work in a week.

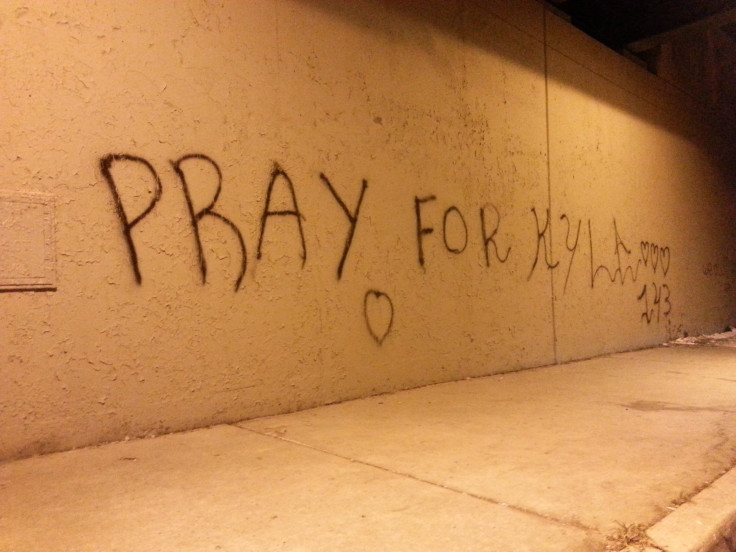

Kyle hit his head so hard that his skull was fractured, his brain swelled, and his neck vertebrae were shifted. Paramedics brought him to a hospital, but Kyle never woke up. Despite the severity of his injuries, his friends tagged familiar spots on Staten Island in public support.

I first met Kyle three years ago, when he was still in high school. He would come into the store I worked at, looking for his older sister. She was another employee, and a good friend of mine. Kyle and I spoke a few times, mostly passing conversations about cars - he eventually went to trade school to be a mechanic. He was quiet and seemed timid around new people, so it was hard to get much information out of him.

But he had a friendly energy about him. His mother and father would regularly visit the store, so I came to know them as well.

When Kyle died, I was no longer working with his sister. I decided to attend the wake anyway, to pay my respects for the young man who had been lost. I had hosted a wake before, so I felt prepared.

Two Christmases ago, my family buried my grandmother, the last surviving grandparent. It wasn’t particularly sad; a ninety year old woman meets and befriends many in her life, but most of those people return to the earth before she does. The visitors mourn, but they’re also relieved that the burden is lifted from their shoulders. She lived a long life, and her loved ones are prepared for her death.

So I pulled on my black peacoat, got into my car and drove to the funeral home, a large establishment on the south shore of Staten Island. I expected to have a similar experience as my last wake.

The packed parking lot gave me reason to question that assumption. When I walked towards the home’s front door, I expected to see a small group of people huddled in a corner, consoling one another. Nothing out of the ordinary.

But then, Kyle was out of the ordinary.

I opened the door, and I was not greeted by a small group - there was a full-on congregation. The line to see the casket looped around the viewing room and snaked all the way to the building’s secondary entrance, some 200 feet away.

I stood in the middle of foyer for a few minutes like a lost child. I wanted to ask someone if the line was all for Kyle. I didn’t think it could be - there were over a hundred people standing in queue from the front door to the back entrance alone. This didn’t feel anything like the last time.

“Yes, these people are all here for Kyle,” a hoarse, but friendly voice called from my right. It was a line that was probably repeated more than a few dozen times that night.

The sound’s speaker was a burly, balding man in a black suit and tie - one of the funeral home’s employees. He pointed to the back of the line and thanked me for coming. As I made my way towards the first open spot, I glanced and the faces of those who had gathered before me, hoping to catch a glimpse of what they were thinking. I immediately regretted that decision.

I found not stolid strength and hardened men, but ones who were struggling to fight tears. Many were coughing in an attempt to hide their reddened faces, so no one would see them cry. It was a strategy I quickly employed, to a similar amount of success.

My throat was closing, esophagus choking on the oxygen I tried to force into my lungs at a semi-normal rate. I tried to prepare myself to be stable and consoling, so I could support the Miller family when it was my turn to see their youngest son. By the time I had made it to the viewing room, I had myself under control. I approached the guest book and took a quick note of the signatures - the book was almost completely filled, which made me smile - and left my John Hancock on the penultimate line. It was one of the neatest examples of my signature; I mentally thanked the years of Catholic school for the cursive practice. I stood prepared to face the family. And then I turned around.

Kyle’s casket was open.

My dinner nearly resurfaced. I looked towards Kyle’s family, and found them all standing intently, as if called to attention by a drill instructor. How could they stand right next to son and brother, and be strong enough to greet and thank all of the visitors? I spent the rest of my waiting time preparing myself again, this time to see Kyle’s face up close.

And I laughed. “You know, they did a good job,” I joked with the dead man. “If I didn’t know better, I wouldn’t believe you were much different from the last time I saw you.” So I turned to face the family, ready to be the pillar of support. Crying time was over. I smiled as I approached Kyle’s parents.

“John, Lori,” I began with feigned joy, “it’s good to see you. I just wish it was under better circumstances.”

Lori’s face caught my eye first. She was there in body, but not spirit - I imagine that losing her son had sent her into shock. She acknowledged me, but her mind was clearly elsewhere. I certainly couldn’t fault her. So I turned to John, intending to give him a hearty, encouraging handshake.

Instead, I saw the utter destruction in his expression. I had come to know John as a rugged, jovial man who never went anywhere without his trademark USA hat and an off-kilter sense of humor.

John wasn’t laughing. His head was bare. He was broken.

We hugged, and I lost any sense of decorum. I had no idea what to say or how to express my sorrow. All I could offer was empathy, so I tried to compose myself and talk to Kyle’s sister. She asked if I was alright.

“Am I alright?” I thought. “You just lost your brother, and you’re asking if I’m alright?” She was calm, almost serene in her manner. I bawled more and embraced her. She thanked me for coming, and reminded me that the funeral would be the following morning.

I told her that I wouldn’t miss her brother’s funeral, even if my life depended on it. Probably not the best choice of words. I exited the viewing room, expecting the foyer to be relatively empty.

But the line was still stretched halfway to the back of the building. Still more people had arrived, to show their love for Kyle and his family.

And I, some jerk who thought he already knew how to help a grieving family, was humbled. Here I thought I could help fix everything, but by myself I’m ultimately powerless.

As, I think, we all are. We can’t change anything that happens, or even “make it better.” Be it fate, decision-making, or divine intervention, what happens in our lives is irreversible.

The only power we have as human beings is community. We don’t have to face tragedy alone.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.