What Is Dark Money? Obama Mulls Campaign Cash Limits Amid 2016 Presidential Contest

The 2016 presidential election is set to blow out records for political spending in a season, with totals projected to rise as high as $10 billion. But one crucial slice of that spending — so-called dark money from corporations, unions and wealthy individuals — has received outsized attention as candidates on both the Democratic and Republican sides gear up their campaigns.

Donald Trump distanced himself from his Republican presidential rivals by swearing against “dark money” spent by outside groups to influence the election. On the Democratic side, Bernie Sanders has repudiated dark money groups, even as at least one organization has planned to run ads in his favor.

Now President Obama has stepped into the debate, preparing plans to require companies that do business with the government to disclose their dark money activities. But given the increasingly complex landscape of campaign spending, what is dark money, exactly? Here are four things you need to know.

1. Dark Money Vs Super PACs

When Donald Trump began lacing into his opponents over independent political support, he used the terms “super PAC” and “dark money” seemingly interchangeably.

Though sometimes related, the two are not identical.

The political action committees known as super PACs came into existence after the 2010 Citizens United Supreme Court ruling, which gave political action committees the go-ahead to raise unlimited amounts of money so long as they disclosed their donors and refrained from coordinating with their favored candidates.

Dark money groups are a different animal. Like super PACs, these 501(c)(4) or 501(c)(6) nonprofit groups can raise unlimited amounts of money. But unlike super PACs, they need not disclose their donors. And under IRS rules, these groups must devote the majority of their efforts to “social welfare,” which comprises a broad and vaguely defined set of activities.

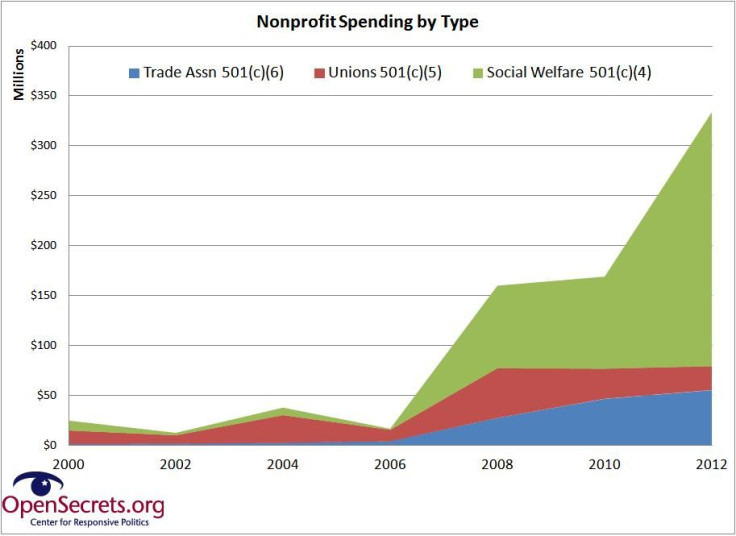

Groups that fall under the dark money heading include nonprofits set up largely for electoral purposes as well as trade associations and unions. But "social welfare" organizations have accounted for the vast majority of 501(c) spending in recent elections. The top five spenders in the 2012 elections were conservative groups.

2. What Dark Money Groups Do

Politically active nonprofits can engage in a number of activities that were once the province of official campaigns, from running attack ads on rivals to sending reams of direct-mail to conducting voter registration drives.

These activities often complement the efforts of official campaigns and their super PACs. And despite their legal differences, super PACs and dark money outfits often have little daylight between them, with dark money groups funneling money to super PACs, keeping the original donors anonymous.

Sometimes the organizations themselves blur together as well. The Right to Rise super PAC has spent at least $40 million supporting Republican Jeb Bush. Right to Rise Police Solutions, meanwhile, has been incorporated as a 501(c)4 nonprofit, and staffers have shuttled between the group and Bush’s campaign.

That group hasn’t produced any ads yet, but others have. Bush’s Florida rival Marco Rubio enjoyed nearly $9 million in supportive TV ads in 2015. According to the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University, dark money spending in 2016 has outpaced all prior elections, setting 2016 up to eclipse 2012’s $300 million in dark money expenditures.

3. Why People Are Upset About Dark Money

Critics of dark money in major elections say that the expenditures allow powerful moneyed interests to influence the course of electoral contests free of public accountability. Corporations, for instance, can support groups that are unsavory to sections of the American public without admitting

For many, especially on the left, energy industry billionaires Charles and David Koch have come to personify the power of dark money. That characterization is clear in the title of a new book by The New Yorker writer Jane Mayer about the Kochs: “Dark Money.”

The Koch brothers helm a network of dozens of interlocking nonprofits that promote libertarian and conservative causes. In 2016, the network plans to dole out nearly $889 million — nearly one-and-a-half times the Republican National Committee’s campaign spending in 2012.

Obama cited the purported influence of dark money groups in his recent State of the Union address. "A better politics is one where we spend less time drowning in dark money for ads that pull us into the gutter,” the president said.

Obama’s potential executive order intended to shine a light on dark money would force companies that have contracts with the U.S. government to disclose their political spending, including expenditures to dark money outfits. The advocacy group Public Citizen estimated that 70 of the 100 companies in the Fortune 100 would be forced to publicize their political spending under such a policy.

4. Opposition To The Opposition

Of course, efforts to pull back the curtain on dark money expenditures have stirred up some pushback.

“The real goal of the disclosure proponents is to harass, intimidate and silence those with whom they disagree,” Blair Latoff Holmes, a spokeswoman for the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, told the New York Times. “We continue to believe that one’s political activities should play no role in whether or not you get or keep a federal contract.”

In recent years the Supreme Court has leaned toward the Chamber of Commerce’s viewpoint, ruling that limits on political spending encroach on the freedom of speech. “Political speech does not lose First Amendment protection simply because its source is a corporation,” the Court held in its Citizens United decision.

The majority applied that same logic to a 2012 decision in which the state of Montana sought to use a decades-old state law to restrict the spending of a dark money group. The Court sided with the political nonprofit. And in a 2014 decision surrounding official campaign spending by individuals — a case not directly tied to dark money — Chief Justice John Roberts reasoned that “disclosure requirements burden speech.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.