What We Know About MH370: Malaysian Airlines Flight Timeline, Facts About Route Still Scarce A Year After Disappearance

Malaysian Airlines Flight 370 disappeared one year ago Sunday, but the world still doesn't know what happened to the plane. The anniversary has everyone from TV broadcasters to aviation amateurs reviewing what it knows in the ongoing international mystery, and the past 12 months of rumors can be confusing. Here are the basics of what we know.

When it left: Flight 370, on a Boeing 777, left the Kuala Lumpur International Airport on March 8, 2014, at 00:41 local time.

Where it was going: Beijing. The flight was due to land in China at about 06:30 local time.

Who was on board: There were 239 people on Flight 370 -- 12 crew members from Malaysia and 227 passengers from various countries. The captain was Zaharie Ahmad Shah, who had more than 18,000 hours of flight experience and ran simulator planes out of his home. His first officer on the flight was Fariq Abdul Hamid, who had about 3,000 hours of flight experience.

One hundred fifty-two of the passengers were Chinese, and 38 were Malaysian. Australia, Canada, France, Indonesia, the United States and India also had residents on board. The oldest person on the plane was 79; the youngest was 2. Read the full passenger manifest here.

Who wasn't on board: Two passengers, Christian Kozel and Luigi Maraldi, were listed on the manifest but not actually on Flight 370. Their passports had been stolen and were used by two Iranians seeking asylum. Thought initially suspicious, authorities determined the duo -- Delavar Seyed Mohammedreza and Pouria Nourmohammadi Mehrdad -- were not terrorists.

When the plane lost communication: The plane sent its last transmission at 01:07, with the final communication from the pilots coming at 01:19. The man speaking -- thought to be either the pilot or co pilot -- said "Goodnight Malaysian three seven zero."

When the world realized something was wrong: Two minutes later, when it entered Vietnam's airspace, Flight 370 did not check in with the local air traffic control. USA Today reported that search and rescue efforts did not start until four hours later, and the plane kept completing so-called "handshakes," or pings, with a satellite over the Indian Ocean until 08:11.

Where it went: Data indicates that Flight 370 turned left and went back over the Malay Peninsula toward the southern Indian Ocean, where experts think it ultimately went down off the coast of Australia.

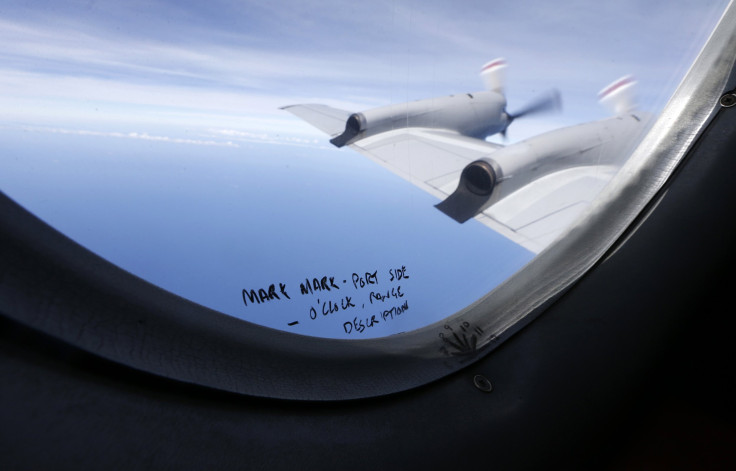

Who was involved in the search: Twenty-six countries, including the U.S., France, China, Japan and South Korea, pitched in to scan the Indian Ocean for debris. The search has cost Australia and Malaysia about $60 million each and could soon wind down. "I can't promise that the search will go on at this intensity forever," Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott said this week. "But we will continue our very best efforts to resolve this mystery and provide some answers."

What has been found: Nothing.

What the government thinks: On Jan. 29, Malaysia officially declared the plane's disappearance an accident. The 239 people on board were presumed dead.

How the families of the passengers feel: Angry. The Malaysian government has been criticized over the past 12 months for its handling of the incident, which at one point involved sending out a text message to families saying their loved ones had likely died. The families have argued that the Malaysian authorities are ignoring, mistreating and hiding information from them. "They don't really care about what we feel or what we have to say," Grace Nathan, whose mother was on Flight 370, told CNN. The relatives' compensation is up in the air, and they say that without evidence, they don't believe the plane crashed.

What happens next: About 9,200 square miles of the Indian Ocean have been combed for evidence, which is about 40 percent of the area the Australia Transportation Safety Bureau plans to search. The hunt will likely end in May.

But that's an expensive option, and representatives from Australia, China and Malaysia have plans to meet to discuss whether to extend the search and how they'll pay for it, according to the Chicago Tribune.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.