When A Coal Company Goes Bankrupt, Who Is Left To Clean Up The Mess?

The gloomier outlook for U.S. coal companies is raising questions about who will pay to clean up shuttered strip mines and open pits across coal country. With financial woes piling up for coal producers, environmental groups are warning that taxpayers could be on the hook for millions in restoration costs if mining companies can’t pick up the bill.

Arch Coal Inc. this week became the latest U.S. coal operator to seek Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in a bid to cut its long-term debt by more than $4.5 billion. Plunging coal prices, sluggish demand and competition from cheaper natural gas are eroding revenues across the industry. The filing Monday arrives after Walter Energy, Patriot Coal and another large producer, Alpha Natural Resources, filed for bankruptcy last year.

The coal sector’s troubles are only expected to deepen as regulators clamp down on harmful pollution from coal-fired power plants. In China, the world’s largest coal consumer, coal imports slumped 30 percent in 2015 due to a slowing economy and the country’s push toward cleaner energy, data showed Wednesday.

“The market is going to be shifting. It’s probably roughly the same size for the next couple of years, but then it’s going to start to decline as folks move on dealing with climate change,” said Matt Preston, research director for IHS’s North American coal division in Annapolis. “Companies will exist as smaller and more sized to the actual market.”

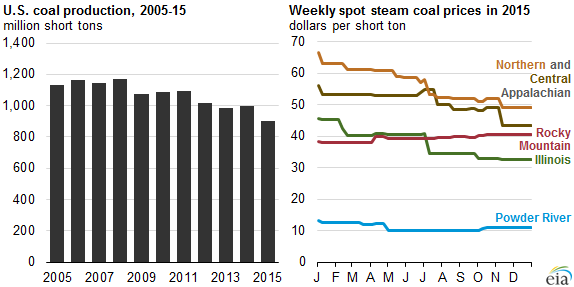

In the U.S., coal production slumped to a nearly 30-year low in 2015 due to industry pressures. Coal production for last year is expected to total 900 million short tons, about 10 percent lower than 2014 production and the lowest level since 1986, the U.S. Energy Information Administration recently reported.

Community groups in coal-rich Wyoming and leaders with the Sierra Club, a national green organization, said this week they worried that coal producers’ financial problems would jeopardize their ability to restore the land and protect the water near mine sites.

“State and federal taxpayers must not be left with the bill,” Bob LeResche, who chairs the Powder River Basin Resource Council in Wyoming, said in response to Arch’s bankruptcy filing Monday. “Bankruptcy should not be used as a haven for the company to escape its obligations.”

A spokeswoman for St. Louis-based Arch Coal and a spokesman for Bristol, Virginia-based Alpha did not return requests for comment.

Environmental lawyers for West Virginia disputed the idea that taxpayers would be forced to pay for mine cleanups in that state. “The coal operator remains on the hook for its environmental reclamation obligations. That remains true whether or not that operator is in bankruptcy,” said Kristin Boggs, general counsel for the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection. “It doesn’t get you off the hook for performing reclamation.”

Coal miners, under state and federal law, must post reclamation bonds to guarantee their ability to restore their mining sites. The Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977 allows individual states to craft their own plans for enforcing the law, so long as they meet federal standards.

Coal companies have a few options for reclamation guarantees. The most common is the surety bond, which is backed by third-party financial institutions. If the company defaults, then it’s up to the insurer to cough up funds for the coal mine reclamation. Some states, including West Virginia, issue pool bonds, which require each mine operator to pay a tax on every ton of coal produced. States can call tap this special funding if a company goes belly-up.

The third and cheapest alternative is “self-bonding.” Companies that meet certain financial standards can issue self-bonds without the backup of a third party, essentially giving states only their word. Arch has roughly $458 million in self-bonded liabilities for its mines in Wyoming. Alpha has more than $600 million in combined self-bonded obligations in Wyoming and West Virginia.

Yet Arch hasn't qualified for self-bonding since 2012, according to securities filings cited by Reuters. Arch instead has self-bonding through its subsidiary, Arch Western Resources. Wyoming regulators last year informed Alpha it no longer qualified for self-bonding status, although the company reached a deal with the state in September to resolve the issue.

Peter Morgan, a staff attorney with the Sierra Club in Denver, said self-bonding raises the risk for states if the companies can’t recover from bankruptcy. “If a self-bonded company does find itself in financial difficulty, if it does end up liquidating, there’s no separate financial assurance,” he said. “At that point the state is on the hook for 100 percent of those reclamation costs.”

Arch and Alpha have assured at least some of their reclamation obligations will be covered.

In Arch’s case, its lenders agreed to cover up to $75 million in cleanup and other regulatory obligations in connection with its proposed $275 million bankruptcy loan. That leaves $410 million remaining in its self-bond obligations to Wyoming.

The Wyoming Department of Environmental Quality did not respond to a request for comment on the two companies’ bankruptcy proceedings. Arch, which holds the country’s second-largest reserve of coal, also mines for coal in West Virginia, Colorado, Illinois, Kentucky, Maryland and Virginia, although it only has self-bonds in Wyoming.

Alpha’s bankruptcy lenders agreed to earmark up to $100 million of its $700 million bankruptcy financing package for cleanup obligations. The company promised about $61 million to Wyoming in the September settlement agreement and $39 million in a separate agreement with West Virginia. That leaves both states holding hundreds of millions of dollars in remaining liabilities.

Boggs, the general counsel for West Virginia, said the $39 million guarantee includes a $15 million letter of credit from Alpha and a $24 million “superpriority” administrative expense claim. If those funds aren’t enough to cover Alpha’s cleanup expenses, the state could next tap its Special Reclamation Fund to cover the remaining costs.

She said that claims that West Virginia taxpayers would be left to clean up Alpha’s mine “is not a true statement.”

Sierra Club’s Morgan said the questions raised by the coal companies’ bankruptcies exposed the need to review decades-old surfacing mining regulations -- particularly around self-bonding guarantees.

“The whole approach was taken at a time when nobody could conceive of there being an across-the-board decline in the demand for coal, like we’re seeing now,” he said. “Unfortunately the regulatory system hasn’t caught up to reality.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.